There is teaching and there is test prep

Throwing money, alternate approaches, nothing has worked

Benjamin Franklin’s old saw “Nothing is certain except death and taxes” needs to be updated. Let’s make it: “Nothing is certain except death, taxes and American students struggling with standardized tests.”

You can blame it on the pandemic, which certainly did not help. But for more years than anyone wants — or dares — to count, American students have continued to struggle with standardized tests. Whether it’s FCAT or FSA or FAST (no irony intended) or even the Advanced Placement tests, generally administered to the cream of the academic crop, things ain’t going well.

And for me, teaching at the one school in the state of Florida that has consistently been 10-15-20 points behind the rest of the state’s high schools, it was a monumental challenge. How do you take kids who are 1-2-3 grades behind reading-level wise and help them pass the end-of-course exam? There are days I’m still not sure how I managed it but one year, I had 58 kids take the test and 57 of them passed. And the one kid who didn’t pass actually apologized to me the next day. He had a fight with his girlfriend the night before the test, he told me, and he was so pissed off, he couldn’t concentrate. “You taught me everything I needed, I just couldn’t do it.” I just about fell over when he told me that.

The first thing I had to get across to the kids is the people that make up the tests DO NOT WANT YOU TO PASS. They are selling a product to school systems and if everybody passes — which, of course, ultimately what the administrators are hoping for. But if the test is declared too easy, they’ll hire somebody else.

Now I want to make clear that for me at least, there was teaching, which is what I tried to do for a good part of every school year, and there was test prep, which is what I had to do when that time rolled around.

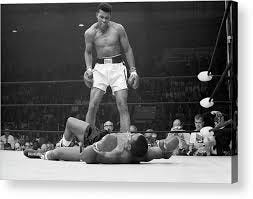

And I’d open my lesson that day explaining that the test makers were not your friends. That they will pull out ALL THE STOPS to beat you. I put up this full-sized poster up on the wall of my room.

I told them they could be Muhammad Ali, standing over the test, or they could be like so many of their previous classmates and brothers and sisters and be like Sonny Liston, flattened by the FCAT, SAT, FAST or whatever it was called, test. Ask my former students. Once they see this picture, I guarantee they’ll remember.

And so we’d dive into the actual test and give them a strategy for taking it. You had to plan. So I’d go into are the traps, the tricks of the trade that these perverse test-makers come up with to baffle the kids.

For example, one year, I had four different students miss passing the test by a single point. And you know why? Of the seven different passages the state kindly threw at the kids on that particular test, one of the passages did not ask a single question that stemmed from the actual passage itself. All the questions came from the footnotes. Though I certainly warned them, each of those four kids each admitted they didn’t read the footnotes on that passage. That’s probably what tripped them up. And that’s bleep.

Another one of the nasty things they’d do is have trap questions. Like “All of the following BUT” or “EXCEPT FOR…” In other words, if there are five possible answers, four will be correct. You have to sniff out the one wrong one. And for kids who don’t have the steadiest of hands at the wheel already, that’s difficult.

Then we’d talk about the KINDS of questions they’d ask. I always encouraged them to look for the RIGHT THERE kind of question, where they’ll say “In Line 27, Mark Twain says….” So you can focus on just that line and try to decipher it. I’d warn them to stay away from the BIG PICTURE sorts of questions, ones that assumed you’d read the entire piece, until you got the very end of the questions because maybe you’d learn enough answering the first batch to make a good guess at the rest.

The most controversial suggestion I made — and I still kind of wince, thinking about some of the crap I took from some of the administrators who argued with me, someone who spent a dozen years in the classroom actually teaching these kids — you’d think they would know better — is that I’d say: “READ WHAT YOU NEED.”

In other words, I was advising kids who ARE NOT readers to not try and torture their souls by reading the entire passage, line by line but instead, to be certain to read the first three or four paragraphs very carefully, which should, in turn, give them a ballpark idea where the rest of the passage is headed.

“I can’t believe you’re telling them not to read the whole passage,” one naive second-year teacher whined at me. “That’s academic suicide.”

No, I explained, it wasn’t. It was giving kids who struggle reading a chance to beat the system. And I still believe that.

And lastly, one of the most important concepts to get through their heads was this — you don’t have to get a100. You only need to get a 70. So that means out of 10 questions, you can — and likely will — miss three and still be OK. I warned them not to spend too much time on a single question, the points are the same for every single one. And also to make sure to answer every single question because for reasons I still don’t quite fathom, they don’t take off for wrong answers. You might guess right!

Now I think it’s a fair question to ask IS THIS THE KIND OF TEST THAT PROVES A DAMN THING TO ANYBODY? Is it fair to have kids in school for an entire year then build it all up to a single day where they better, by God, have their act together if they want to go to the next grade.

I fought that fight for a dozen years. Overall, I think I helped a lot of kids get through the test, kids that I’m pretty sure would not have made it without my radical beat-the-system techniques. But should I have had to resort to that? That’s a question that the Department of Education here and across the country ought to think about. Maybe THEY ought to take a test. And I’ll say this: I ain’t helping them study.

CHECK THIS OUT:

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

The NAEP, also known as the nation's report card, shows that students' knowledge and skills have declined, and the gap between the highest and lowest scorers has widened. For example, in 2022, 9th graders' average scores declined 5 points in reading and 7 points in math compared to 2020. This was the largest average score decline in reading since 1990, and the first ever score decline in math.