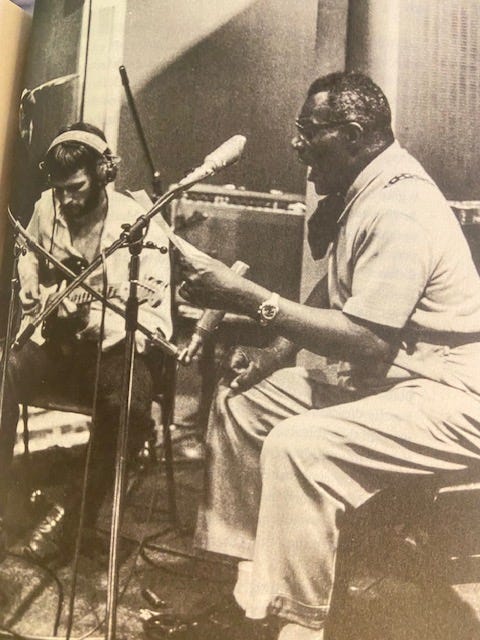

The instant I saw this photograph from the Michael Ochs Archives, obviously taken during the recording of “The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions,” in May 1970 at London’s Olympic Studios, I knew I had to write about it.

There’s just something about this photo that grabs me; the modern guitar hero Clapton with his head down, ears open, headphones on, lost in deep concentration, focused on his hands finding the right place up the neck of his Stratocaster. Next to him, the dominant figure in the photo, the giant Wolf sitting up straight, holding a lyric sheet in one massive hand, mouth in full glorious howl.

I found the picture on Page 435 of Peter Guralnick’s “Looking To Get Lost,” a sort of end-of-the-road compilation/reconsideration/semi-memoir of his devotion to, then his writing about, music. By my count, it’s Guralnick’s tenth book; it came out in 2020, roughly a quarter century after his definitive two-part biographies of Elvis Presley: “Last Train To Memphis” (1994) and “Careless Love” (1999) so he’d had some time to let all he’d written and all he hadn’t truly sink in.

The reviews of both books were overwhelmingly positive, very complimentary but that doesn’t mean Guralnick got it all. Not that he didn’t try as hard as a man can, but writing about music is ephemeral, subjective, elusive. It can change on you. And evidently, it did for Pete.

I still remember Guralnick writing in “Lost Highway,” before the Elvis bios, coming up with this stunning dismissal: “You are left with the inescapable feeling that if he never recorded again, if Elvis Presley had simply disappeared after leaving the little Sun Studio for the last time, his status would be something like that of a latter-day Robert Johnson - lost, vulnerable, eternally youthful, forever on the edge, pure and timeless.” Say, whaaaaaat? You’re writing off ALL ELVIS from 1956 on?

Now, the record they’re laying down tracks for in this photo — “The Howlin’ Wolf London Sessions” wound up being pretty good. Both Wolf and Clapton have done lots better albums and Wolf himself hasn’t said many complimentary things about those London Sessions.

But the concept behind it, re-discovering, you might say, a old weather-beaten, juke-joint haunted, proud old man still doing what he always did, putting his heart and soul and that kerosene-soaked, tobacco-and-whiskey cured pipes to work in this modern-era recording studio, one of the finest in London, working alongside this brand new, celebrated, some would say worshipped (Remember: “Clapton is God”) guitar hero who, if the stories are true, was so overcome by wanting, needing, aching to play the blues just so, he apprenticed himself to his bedroom, his record player and the guitar for so many years, some wondered when/if he’d come out. And what would he play like when he did?

Like most kids my age (18) when the record came out, I only had half the backstory and probably the PG-version at that, following the career and the fleet fingers of Eric Clapton from the Yardbirds to John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers to Cream to Blind Faith to Derek and the Dominos. Though I didn’t play guitar (not yet), I memorized the guitar solos as if they themselves were the song — “Have You Heard,” “Steppin’ Out” “Sunshine Of Your Love” “Crossroads” “Badge”, “Let It Rain” — then upping the stakes even more with “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad” and “Anyday” and “Bell Bottom Blues” and my God, the national anthem, “Layla.”

I knew my Clapton and yeah, was ready to argue vs. Jeff Beck, vs. Jimmy Page, Vs. Pete Townshend, vs. Alvin Lee, maybe even vs. Jimi Hendrix, though Hendrix mostly played as if what he was recording could only be heard and understood on another planet.

I didn’t know the other half of that story, the Wolf part and that of all the founding, under-the-radar bluesmen Clapton fed himself on, Muddy Waters and Otis Rush and Buddy Guy and Freddie or B.B. King and on and on. I’d heard and read about, saw their names underneath song titles on some of the records, heard Clapton speak about them reverentially in interviews, but the one that intrigued me the most, Howlin’ Wolf, came from reading Guralnick’s profile in his wonderful “Feel Like Goin’ Home.” The way Pete described him, his music, his on-stage act, his intensity and remarkable way of commanding a stage, I had to hear this music for myself.

I went out and bought “Howlin’ Wolf” and “Moanin’ At Midnight,” found out all about Hubert Sumlin, his crackerjack guitarist and loved the Wolf’s hand-stamped music. Instantly. I could see why Sun Records’ head Sam Phillips (who discovered Elvis, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Charlie Rich and others) said the one guy he wished he could have kept recording with was Wolf. That voice, that presence, that command. You bet that microphone had better stand at attention when the 6-foot-3 Howlin’ Wolf was singing into it.

The idea of getting these two together with cast of notable British musicians (who, I was pretty sure weren’t into Wolf the way I knew Clapton was) sounded great as a concept but in practice, I thought there would be a language barrier that had nothing to do with a Cockney accent. They couldn’t quite get there.

But I could. And one great thing about these bluesmen, it’s not like Wolf had an enormous backlog of material for me to catch up with. It’s an album. There were maybe a dozen epic, show-stopping tracks — “Smokestack Lightning” and “Back Door Man” and “How Many More Years” and “Killing Floor” and “Little Red Rooster” that carved their spots on my mental jukebox.

They fit nicely, right alongside Clapton’s work, perfect. For me and my apprenticeship with the blues, I didn’t need Muddy or Freddie or B.B. or Buddy, Wolf gave me a genuine taste that lingers still.

But how did it fit so readily, so automatically, into my musical world? It was as if there had always been a spot for it, I just had to plug it in. When that happened, it made me wonder if I ought to place my hundreds of records laid out like train tracks, showing the connection, how one led to the other.

You know, how it went from Elvis to The Beatles to the Stones, from Bob Dylan to The Band, from Bruce Springsteen to U2, there’s some sort of progression in there, right?

Like from Clapton to Jeff Beck to Rod Stewart and the Faces to Led Zeppelin. Got that.

But how did I wander over to Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music? Then Big Country? To The Replacements and Paul Westerberg?

I can see going from Hank Williams to Jerry Lee Lewis to Johnny Cash and Tom Petty. I can even sort of see James Brown going to Marvin Gaye to Motown.

But from The Who to The Clash? And Neil Young (105,235 words and counting)? Where in the hell did he come from? He can’t be explained and I bet he’d be delighted with that.

So, I go back to that photo, two very different men with very different backgrounds and skill sets trying to find a way, a song, a moment to connect. And hope that when and if that happens, somebody has the damn tape recorder on and maybe, just maybe, we get to hear what they created in that moment. And somewhere, wherever we might be, we connect, too and the circle — same shape as a record or a CD — is complete.

I think if Howlin’ Wolf was still around and came to my house, thumbed through my record collection and saw “The Howlin’ Wolf London Sessions,” he’d laugh, that booming, clashing, commanding voice that would make the glass on the framed pictures in my den, shake.

“Play this, “he’d say, settling into a comfy chair, folding those Size 13’s on top of one another. “I dare you.”

The blues offers the greatest source of universal truth there is.

Great piece John !!! For a ‘history geek’ such as myself it’s so interesting to hear the way music changed over time, especially since 1900. While as you say there are some places where music traits trail off in different directions, there is still a succession of influences a trail of sound that you can hear leads to today. Great photo by the way!!!