Editor’s Note: A dozen years ago, after spending so many years reading about Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash and John Hammond on my free time while I was teaching Henry Thoreau’s “Walden” in my daily classroom, I got to wondering what might have happened if Dylan HAD played Woodstock? Other than a few expense reports, I hadn’t really tried to write fiction since my college days. But I gave it a shot and sent it to the wonderful Karl Erik Andersen who runs the Expecting Rain website in Norway and he was nice enough to run the whole darn thing. I hadn’t read it since I wrote it until the other day. There seems to be so much interest in Bob Dylan once again — by the way, I called it that Timothee Chalamet would play “Tomorrow Is A Long Time” on SNL! — I thought my loyal Dylan readers might enjoy this imagined Bob Dylan appearance. Since it’s long, I broke it into two parts. Here’s Part One:

BOB DYLAN AT WOODSTOCK? (PART ONE)

AUGUST 16, 2013: Editor’s Note: This didn’t actually happen – as far as we know. But if you let your imagination run, it could have, couldn’t it?

Line 1 was lit. The voice on the other end was Old World money, wrapped in a smile.

“Rachel, I’d like you to do something for me...”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’d like you to go down to Crawford Doyle and have them get me a first edition of ‘Walden.’ When you get it, I’d like you to send it right away to Hi Lo Ha. I also have a note I’d like you to enclose for me.”

“Yes, sir.”

Hi Lo Ha. She knew what that meant. A first edition of “Walden.” Why “Walden?” And it’s going to Hi Lo Ha. Wouldn’t the world like to know that? Hi Lo Ha.

Summer was fighting its way into New York City. The streets were wet and messy and up on the 11th floor office of the CBS Building, life was good. Sales were better. Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” had been a smash, Blood, Sweat and Tears were rolling, Johnny Cash was still soaring after last year’s “Live At Folsom Prison” record claimed about every award in sight and set him free. A prison album setting a guy free, who would have thought it?

Why, Bob Dylan’s startling but slight burst of “Country Pie” (an actual title!) of his excursion into country music, “Nashville Skyline” had climbed all the way to No. 3. And you could hear “Lay Lady Lay” on the radio any time. The slight record – it was barely half an hour, Ragtime Country Bob dipping his big toe into the Big Muddy of Country Music – slid down the charts just as quickly.

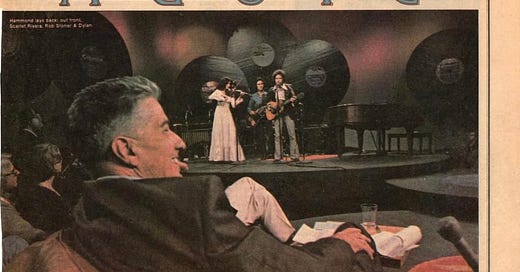

CBS’s John Hammond, who discovered Bob Dylan, listens in that famous PBS Special honoring his contribution to music. What if Hammond tried to get Bob to play at Woodstock?

Hammond, sitting at his desk in his office on the 11th floor, wondered what was next. And what he could do about it. As the final summer of the sixties approached, there was an unsettled feeling from coast to coast. The inspirational leaders – our leaders – were all gone, stubbed out like a cigarette. Martin Luther King, John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy. They were erased from our lives and our world just as easily as Mick Jagger – then recording “Sympathy For The Devil” - was able to trot into a studio and simply add an “s.” -“You shouted out who killed the Kennedy(s.)” Yeah. It was that easy.

On the way into work that morning, Hammond had heard The Fifth Dimension’s hit “Let the sun shine? Let the sunshine in?” and wondered, wasn’t that really a collective prayer for all of us? Who was going to bring us sunshine? Bob? Maybe Bob Dylan…

Scanning the front page of the New York Times that spring morning, Hammond felt discouraged. Nixon? He was enough to discourage anybody. Helicopters spraying stinging powder at war protesters in California. Race riots. Insanity. It seemed like every day sunk us deeper in the bitter quicksand of Vietnam and political upheaval, yet the music, almost in defiance of all that, was soaring, reaching out, lifting all of America’s young people past this crap.

Hammond, who had spent his life in music, loved this idealistic trend. Was it pulling them inexorably towards a future that they could really command. Who could ignite that final, everlasting spark? He looked at a photo of Bob, a young Bob, sitting on the corner of his desk. We need that voice again. That’s what made Hammond call Rachel and place that order.

As Hammond sat at his desk, looking over his own well-worn copy of Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden,” as he had last night, he felt like he had to do something. He had to reach out. The idea of the reclusive Thoreau, boldly addressing the world from that immaculate little cabin out in the Massachusetts woods, that appealed to Hammond. Maybe it would appeal to Bob.

Dylan was holed up at Hi Lo Ha, being a family man and all. Which was great. But he had something inside, burning. Columbia’s president Goddard Lieberson tried to inspire Dylan when he was writing what would become “Tarantula.”

Bob at home in Woodstock

He presented Dylan with a rare first edition of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and never heard a word more about it. Next thing Lieberson knew, Bob was writing country songs.

No, Hammond thought, Bob wasn’t going to be a revolutionary, well, not like he was. Not any more. We weren’t going to see him draping huge American flags behind his stage set like he did in London and Paris or hear him talk about his tax bracket (“Uncle Sam, he’s my uncle! Can’t turn your back on a member of the family!)

But wasn’t everybody waiting to hear what he thought? Surely, he wasn’t going to ignore this ugly Vietnam War. He’d sung about all these injustices so brilliantly before. He could, he should do it again. Maybe he needed a little nudge. Everybody needs a little nudge now and then.

Hammond, of course, knew Bob Dylan could – and would - do as he damn well pleased. When Hammond first heard the acetates of “Skyline” and Bob’s high, sweet voice crooning – well, that’s really what it was – these expertly crafted but hardly revolutionary tunes, Hammond could only smile.

“Holding pattern,” he thought. “He loves Johnny Cash, the two have been hanging around…it’s a temporary excursion.” Or so he hoped. There was no question about it, the guy who, just a year or two earlier had seemed to be able to explain or summarize, depict, dramatize or decry any and all of this maelstrom of a world – sometimes in the same verse – was now singing things like “Love to spend the day with Peggy Night.” Not touring.

The time, Hammond thought, was now. This Bethel festival, up near Woodstock, this was the platform. Why, just one acoustic set – “Masters Of War,” “Hard Rain,” “Times They Are A-Changin’” – the whole damn crowd would up and march right down Pennsylvania Avenue and DEMAND CHANGE. End this war. We could correct the path of the country, these kids, these crazy kids.

Hell, it was a crazy idea, sure. But in this year of change, it almost seemed like our last chance. Michael Lang, the kid who was promoting that festival, was going to invite Bob, he’d heard. Lang was supposed to even have a private meeting with him. Hammond wouldn’t try that. Too pushy.

If the RECORD COMPANY wanted him to do something, encouraged him to do something, even to CONSIDER something, Dylan would run the other way. Thoreau would have loved that about him. He had to try something else.

***

Her heels clicked on the hardwood floor as she entered John Hammond’s office. The room smelled of stale cigarette smoke and Old Spice, or something like that. Hammond was leaning back in his chair, tie flipped over, glasses half-way down his nose, running his hand over his brush cut. When he saw her, he smiled broadly, those eccentrically askew teeth quickly unveiled once more. His voice was flat, soft, inviting.

“Here you are,” he said, reaching up to hand her the small yellow envelope. “You’re going to the bookstore now?”

“Yes,” she said, smiling. “Thank you, sir.”

The floor creaking beneath her, she walked out, turning the envelope over once she was out of his sight. Sealed. Why would John Hammond want to send a book, an old book at that, out to Hi Lo Ha?

She had called Crawford Doyle and asked if they had – or could get – a first edition of “Walden,” and there was a sort of sarcastic chuckle on the other end.

“Sure,” the voice said. “It’s not cheap, though.”

“It’s for Mr. Hammond.”

“Oh, OK. Give me till the afternoon,” he said and the phone clicked off. She got up and walked over to the book cabinet against the far wall. There wasn’t much help in old Billboards and music magazines and sheet music. In an old World Almanac, she found something that mentioned the author, Henry David Thoreau. But nothing about the book’s sales or even what it was about. It really wasn’t any of her business, she knew that. But how could she not be interested in finding out why Hammond would send such an expensive book out to Hi Lo Ha? And Bob?

She knew Mr. Hammond had been on the phone quite a bit with Bob Johnston from Nashville in late April, a couple weeks after “Lay Lady Lay.” But why “Walden?” Why now?

At lunch, she walked over to The Corner Bookstore – they knew her at Crawford Doyle – and asked about “Walden.” A young employee steered her to a musty corner. She took a copy down off the shelf and handed it to her.

She opened, by accident, almost to the end of the book, just like she always did in high school, trying to see how the book would end. The words seemed to spring off the page.

“The surface of the earth is soft and impressible by the feet of men;” she read, “and so with the paths which the mind travels. How worn and dusty, then, must be the highways of the world, how deep the ruts of tradition and conformity!”

Tradition? Conformity. What would that mean at Hi Lo Ha? Marriage? Kids? Escape? This Thoreau character seemed almost radical as he seemed to speak to her from the yellowy pages of this weather-beaten old book. Hi Lo Ha.

Was this what Hammond was getting at? Putting Bob Dylan and tradition and conformity in the same sentence? Thoreau’s hell-bent words had a certain ring to them, even now. She sat in a soft green chair in the corner and continued what looked to be the final chapter. Was this what Hammond was getting at? “…if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary; new, universal and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and within him…and he will live with the license of a higher order of beings.”

A higher order of beings? Isn’t that how Bob lived anyway? Trembling a little bit – this was heavy stuff to consider at lunch – she read on, thinking, as Hammond had, about the slender recluse who climbed down off the zeitgeist to become Mr. Mom.

“In proportion as he simplifies his life,” Thoreau continued, “the laws of the universe will appear less complex and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness. If you have build castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.”

Hi Lo Ha. Dreams. Foundations. Laws of the universe and Castles In The Air. Maybe that’ll be Bob’s next album title. “Castles In The Air,” the long-awaited follow-up to “Nashville Skyline.” She laughed to herself.

She was putting the modern copy of “Walden” book back on the shelf when they hollered from the front of the store. They would have the book in a day or so, they told her. She walked back to the office thinking about what she had read.

“He will put some things behind…”

She had on her AM radio back in the office a little while later when “Lay Lady Lay” came on. Strange song. Mr. Hammond walked in just then, taking a little later lunch than usual. He smiled and nodded.

“Ah, Bob,” he said, rapping on her desk with his knuckles and walked out. She looked at the yellow envelope again, wondering what was in that note.

***

It was a few weeks later when Rachel felt a presence at her desk. She was in the middle of typing a letter and when she finished, she turned around and saw Johnny Cash standing there.

“Mr. Hammond wanted to see me,” he said, that pine-pitch resonant voice – all angles – rang around the walls of her office.

“Johnny!” a voice cried out from behind the door. “Come on in.”

Almost before Rachel could get up, Hammond was in the doorjamb, a huge smile on his face.

“Great to see you. Just great.”

The two men embraced and Rachel stood there for a moment. Seeing Johnny Cash in person, he seemed so, well, regular. Like a guy you’d hire to fix a roof or hook up an icemaker. She’d seen Dylan only once, a wraith wrapped in black sunglasses and cigarette smoke. Cash looked so different to her, she couldn’t get over it.

Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash and Bob Johnston

Hammond, in such a rush to greet Cash, immediately beckoned him deeper into the office and didn’t shut the door. Rachel started to go close it but didn’t want to get in the way. She couldn’t hear all of the talk, just something about the Folsom album. How exciting it was, what a great idea it was to do it in the first place. How do you think San Quentin will work? Did you enjoy working with Bob?

Cash’s voice carried.

“Ain’t no one I’ve ever met like Bob Johnston. That boy is crazier than a shithouse rat,” Cash said. “Had fun with him onstage.”

Hammond laughed. “I was introducing a song, telling the inmates that this was going on record and that I couldn’t say “shit” or “damn…” Hammond’s laughter was rising. “I looked over at him. ‘How’s that grab you, Bob?’ We got it. Don’t think that’ll make the record.”

More laughter. Hammond said something about “Dylan working with Bob now, too.”

“I know,” Cash said. “I stopped by the other night at Music Row – and we sang a bunch of my songs, the mikes were all set up for us and all. It was fun.”

Mumble. Mumble. Hammond had lowered his voice and she couldn’t hear.

“I’m worried, too,” Cash said. “How can I help?”

Rachel’s ears perked up. Help? HELP? Line 1 lit up. She jammed the button quickly.

“Yes?”

“Rachel, can you bring Mr. Cash and I some coffee?”

She got up and walked down the hall to the coffee machine, heels clicking all the way. She must have been walking faster than usual because two different people she passed in the hall sort of moved out of her way.

When she came into the office with the coffee, the two were talking about a festival in Bethel. Not all that far from Hi Lo Ha.

“They’re just about holding the damn thing on Bob’s lawn,” Hammond was saying. “He doesn’t need that kind of pressure right now.”

Cash was nodding, collapsed into a chair, long legs crossed, foot a-bobbin. He was looking at the floor and seemed surprised when Rachel walked in with the coffee.

“Thank you, Rachel.”

She smiled at Cash and walked back to her desk. The phone rang. It startled her.

“Mr. Hammond’s office… He’s in a meeting right now. I can’t… I can’t interrupt…No…Can I….No. Oh…I understand. Hold please.”

“Mr. Hammond, I apologize for interrupting. I have a rather insistent call from a Mr. Johnston from Nashville. He said you had asked him to call?”

“Oh, yes. Yes,” Hammond laughed and slapped his leg. “Put him through.”

“Bob? Well, I appreciate you calling me right now. It gives me a chance to stop listening to Johnny Cash complaining about his producer.”

Much laughter all around. Cash sat up. He could hear Johnston’s voicea Hammond held the phone away from his ear. That Texas twang was distinctive.

“You’re damn right,” Johnston told Hammond. “I had to take the damned fool to a prison to get me a hit record. How bad is that?”

Hammond laughed and turned to Cash.

‘It’s a wonder they let the son of a bitch out,’” Johnston said, louder, knowing Johnny would hear. More laughter.

“You know, I think I can get this on speaker… Rachel..come in here..”

She was up and in there – almost too quickly. She had been listening. “Service!” Cash laughed as Rachel came in. “We sure don’t that kind of service up in Nashville.” Rachel walked over to Hammond’s desk and pushed a button, then placed the phone beside it. Hammond reached out and touched her arm and whispered.

“Stick around…in case we lose the connection.”

Hammond leaned down towards the speaker.

“Bob? Can you hear me?” Johnston’s twang crackled out of the speaker: “Has Cash been arrested yet?”

Laughter.

“Not yet,” Hammond said. “It’s early though.”

“Well, you wanted me to call and talk about how the sessions are going, John. They’re going OK, I guess.”

“How so?”

“I don’t think Bob knows quite what he wants to do. The other day, he asked me – straight out – what did I think about him recording some other people’s songs? I laughed. I mean, if I’d have suggested that when we were doing Blonde On Blonde, he’d have bitten my head off. Or just walked out and I’d be out of a fucking job.”

“So, what did you tell him?” Hammond asked, listening intently.

“I told him I thought it would be great, if that’s what HE wanted, not because some dickhead suggested it.”

Cash sat up, “Why didn’t you ask him to record an album of MY songs, Bob? I could use the money.”

“Christ, Cash, you don’t have a whole album’s worth of songs,” Johnston said. “You stole one from a god damned inmate to fill out your last album?”

They all laughed. Hammond held the San Quentin album cover up and pointed to the last song “Graystone Chapel” (written by San Quentin inmate Glenn Shirley) and nodded.

“I’d like to get Dylan writing again,” Hammond said softly. “We need him.”

When Cash looked up, Hammond gestured to the old photo of Dylan on his desk. “Not just Columbia Records, Johnny, us.” He gestured with arms spread.

Cash nodded.

“Well, he sure was great on my show down at the Ryman,” he said. “Nervous as hell like someone was going to jump out of the audience after him. But you know, Bob’s shy about some things. He was in tune, though.”

“He wasn’t for me, Christ,” boomed out of the speaker. “I got McCoy and Buttrey to try and re-work some of the rough tracks and it was a god damn mess. You know you ain’t going to get Take Two out of him.”

Hammond sat up.

“Well, Bob, we appreciate all you’re doing to try to help him,” he said. “It’s a rough patch for him. He’s had enough of Albert – well, haven’t we all – and I don’t think he’s feeling real sure about himself.”

He looked over at Rachel and raised a finger to his lips. Then motioned it was OK for her to go. The heels clicked on the wooden floor as she left.

“Thanks again for everything, Bob.” Hammond said, looking across the room at Cash. He pushed the button.

“John, we need to talk,” Hammond said. “Let’s go take a walk.”

***

The two walked past a newsstand. The newspaper headlines were all Vietnam. Hammond stood and looked at it for a moment, then kept walking.

“You know, John, I’m sorry we didn’t support “Bitter Tears,” Hammond said. “We just didn’t. As a label. I really liked what you were saying and doing. It took courage. Who else would say a word about the Indians? “Perhaps I shouldn’t say this – you and I have never spoken about politics – but I always admired how Bob was always on the forefront, politically. He seemed to be able to anticipate what was going to happen or maybe, he wrote it, they made it happen. I’m not preciseIy sure what came first.

“But there was a power, a conviction in his writing that seemed to change people…the way they looked at things. It didn’t come from sit-ins and protests and draft card burning but there was an idealism somehow, of what we could be, maybe should be.

“Now, I don’t know how you feel about Vietnam but...” Cash stopped in his tracks. He could see where he was going.

“Are you thinking about Bethel?” Cash asked, hitting Hammond’s shoulder. “That’s supposed to be a big damned deal..”

Hammond smiled.

“It might be a huge audience,” he said. “We don’t know but they have quite a lineup, I hear. Think of the impact a voice like his could have there.”

He took a couple of steps, then stopped.

“Maybe he’s unsure of himself but can you imagine the ovation if – and let’s just say if – he walked out onto that stage unannounced, guitar in hand….?

Cash smiled and nodded.

“I mean, hell, are we going to look to Country Joe McDonald to speak for all of America’s youth?”

Cash laughed and nodded. Hammond continued walking – and talking. “We don’t know how big this festival is going to be – they do have quite an array of stars there.”

“Not me,” Cash laughed. “I ain’t hip enough.”

“They’re not smart enough,” Hammond corrected. “Now, imagine if you and Bob walked out there… unannounced…just the two of you in similar outfits, carrying acoustic guitars, ready to change the world.”

“Naw, it’d be like a barbecue-flavored fart in church,” Cash said. “Me and Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix on the same stage. Ol’ Sam Phillips would disown me.”

“What is Sam doing now?” Hammond asked, turning the corner into a stiff summer breeze.

“He just sold Sun,” Cash said. “I think he’s had it with the music business.”

“Wish we could have brought him to Columbia but somehow, I don’t think Sam would flourish in a corporate structure. Sometimes I can’t stand it around here myself.”

Cash laughed. Funny how even the higher up people go, they still chafe against the corporation, the administration, the bosses, Cash thought. Even Hammond doesn’t like his bosses. Is that where America is headed. More bosses, more higher-ups?

“But, you know, John, to continue what we were discussing… I know I shouldn’t say this…but…if Bob walked out there on that Bethel stage, and let’s say, oh just imagine he decides to do this acoustic…and he played “Masters of War” or even “Hard Rain” or “Blowin’ In The Wind” or any of those old powerhouses, why there’d be a revolution, a youth revolution…and, I’m telling you, we’d be out of Vietnam by the end of the year.”

Cash stopped for a moment, thinking,

“I agree,” Cash said but added, softly. “It’s hard to imagine him doing that…right now.” He paused, collecting his thoughts, measuring his words.

“He really seems to be somewhere else,” he continued. “I tried to talk to him about something I’d read about the war and he was just ‘Leave me out of it.’ He thinks everyone thinks he has “The Answer” or something.

“He was telling me about the lunatics hounding him, even out at Hi Lo Ha. He’s out in the yard with his kids and they’re driving by or honking the horn or pointing him out wherever he goes.

“I mean, we all have to deal with that shit,” Cash said, shrugging. “I just laugh it off – or try to. But you know Bob. He, you know, he keeps a lot inside. When he did my show, he was nervous as shit. I had to pull a few pranks to loosen him up.”

“Well, I’m worried about him,” Hammond says, stopping to look Cash directly in the eye. “I mean, I sort of feel like his father, in a way. I think he’s sort of stuck right now.

“He is enjoying a break, loves his kids and his life but there’s an undercurrent there that troubles me a bit. He says that he doesn’t want to be any sort of spokesman, that he’s just a musician, then he comes out with “John Wesley Harding” with these Biblical themes and ideas. The music doesn’t sell that album.”

“But it does on “Skyline,” Cash said, laughing. “It’s that steel guitar.” “Well, I know he loves you,” Hammond said, “When you stuck up for him that time, on Broadside, you don’t know what that meant to him.

“I know he’ll listen to you, hell, he needs to listen to you. You’re on top of the world! He just needs to understand that he doesn’t need to do anything but write about his life – as it is. Put his heart on the page, the way Thoreau did. You ever read him?”

“Who?”

“Thoreau? Guy who lived in the woods.”

“I read Khalil Gibran,” Cash said. “June got it for me.”

Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden”

“Well, I sent Bob a book, his book, Thoreau’s “Walden” for his birthday,” Hammond said. “It’s a diary, really, about a guy who lived his life and didn’t give a shit about anyone or anything that didn’t interest him. I think right now, Bob is trying to please too many people – he’d never admit that, of course. But from what I hear from Johnston…,”

“You can’t believe that asshole,” Cash quipped and the two of them cackled. Mr. Johnston, a Hammond favorite, was a bit of a rogue. You could understand why, a few years later, Dylan would describe him as someone who should show up wearing a cape, brandishing a sword, a guy who lived on “low-country barbecue.”

But Johnston, who worshipped Dylan, once calling him “a prophet” and someone “touched by the Holy Ghost” might not have been the guy to move Dylan in any particular direction.

Of course, everybody has ideas for him and Dylan, Johnston would explain later, never exactly says “no” or “yes” – he figures it out on his own then says what he wants to do.

Right now, Hammond was saying to Cash, Dylan was so skittish, he might vanish in an instant and never record again.

“He’s calmed down so,” Hammond said. “I almost wonder if maybe he’s a bit depressed. I know he’s trying to change his life, the smoking, the drugs, the wild pace. It’s a complete turnabout. Almost too much of one, you know?

“With this damned war, the assassinations, every day it’s something scary out there, he doesn’t want to be anyone’s target. You can’t blame him.” “Hoover probably has a file on him already,” Hammond nodded, stopping to light a cigarette. “You, too. You’re lucky you got out of Folsom. AND San Quentin.”

“We need to do something about these prisons,” Cash said. “It’s heartbreaking how these men are being treated, John. I mean it. I’m going to do something about that.”

“Maybe you can do something about it, Johnny. You should. But…about Bethel, if you can just talk to Bob about it, let him just get out there and feel that love. I think he feels like he has nothing to say or that he’ll say the wrong thing or that they’ll misinterpret him or ask him to explain his songs or whatever,” Hammond said.

“But they want to love him. If he walked out there, unannounced, with that Martin…I don’t know what would be comparable to that.”

“It’d be a helluva sight to see,” Cash said, crossing the street back to the CBS building.

“These may just be an old man’s dreams,” Hammond said as he opened the front door and Cash smiled.

“We’ll see you later. “I like the way you think, Mr. Hammond. I do have an idea.” Cash said. “Let me get back to you.”

***

Three nights before the actual Woodstock Arts & Music Fair was to begin up near Dylan’s Woodstock home, Cash was getting ready for his Saturday night show at the Ryman in Nashville – The Johnny Cash Show – and he caught up with Bob one last time.

The music papers were full of rumors about this upcoming festival. The Beatles were going to show up. So were the Rolling Stones and Dylan, why, he lived about 5 minutes away. OF COURSE, he would be there.

Cash knew damn well that wasn’t going to happen. Not the way everybody expected it, anyway. Dylan was, as usual, non-committal.

Newspapers were after him, was he going to appear, was he going to make a statement. “Yeah, I’d love to spend the day with Peggy Night or spend the night with Peggy Day,” he might say, and giggle. Or maybe silence is a better way to handle it. Let ‘em wonder.

Cash had asked him straight out. And Dylan hemmed and hawed. “They invited me,” he said. “So I guess I could go If I feel like it. Or not go."

His words just hung in the air like clotheslines.

END OF PART ONE

John Nogowski is the author of Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography 1961-2022, 3rd edition, is available now on Amazon.

hahahaha

thanks. haven't read it yet. 🙂