Editor’s Note: Bob Dylan turns 83 tomorrow. To honor the old guy, I thought I’d share an excerpt from my book: “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography” about Bob’s remarkable speech at MusiCares in 2015. For a guy who’s always been careful about what he says, he really lets it go here. Hope you enjoy it as much as I - and Bob -did.

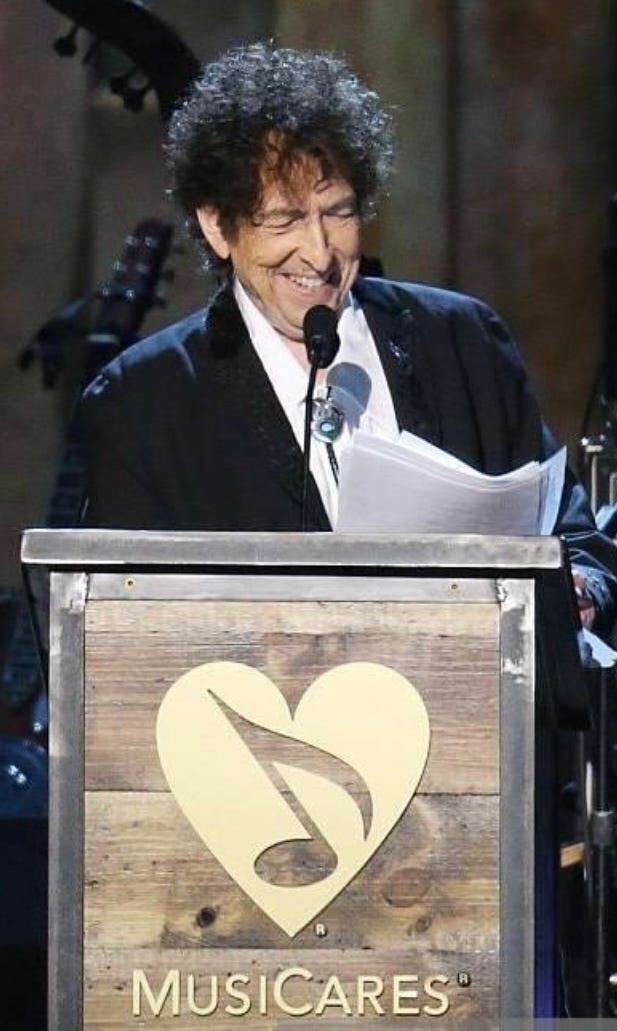

Dylan Speaks Again: The MusiCares Speech

Bob Dylan was named the 2015 MusiCares Person Of The Year at the 25th annual benefit gala at the Los Angeles Convention Center. The night was a lovely celebration of Dylan’s music, with all sorts of big-timer taking their turn at a Dylan song. Neil Young did “Blowin’ In The Wind,” Bruce Springsteen did “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” with Tom Morello and the cast was impressive – Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, Willie Nelson, Beck, Jack White, John Mellencamp, Los Lobos, Norah Jones and Crosby, Stills And Nash.

Former President Jimmy Carter introduced Dylan this way. “Bob Dylan knew how to put the essence of all the world’s great religions into beautiful lyrics which have been an inspiration to me and to the whole world,” Carter said. “There’s no doubt that his words on peace and human rights, are much more incisive and much more powerful and much more permanent than any President of the United States.”

Typically reticent in most public settings, including his own concerts (other than to sing), here Dylan steps up to the rostrum, sheets of paper in his hands and the audience got quiet. Were we going to hear a speech? For a little over half an hour, that was exactly what the audience got, a genuine Bob Dylan speech and it was a valedictory address.

He began by generously thanking many of the people who’d helped him get started; John Hammond, who signed him to Columbia Records, Lou Levy and Artie Mogull, men who were important in getting him established as a songwriter, and then a list of artists who either recorded his songs – The Byrds, Sonny and Cher, The Turtles, Peter, Paul and Mary, Nina Simone, The Staple Singers, Jimi Hendrix – or became his friend, Johnny Cash or lover/friend, Joan Baez.

Then, as he did in “Chronicles, Vol. 1,” he began to talk about how his songs came to be, their roots, you might say. To him, what he wrote was simply following a time-honored tradition.

“These songs didn’t come out of thin air,” Dylan said. “I didn’t just make them up out of whole cloth. Contrary to what Lou Levy said, there was a precedent. It all came out of traditional music: traditional folk music, traditional rock & roll and traditional big-band swing orchestra music.

“I learned lyrics and how to write them from listening to folk songs. And I played them, and I met other people that played them, back when nobody was doing it. Sang nothing but these folk songs, and they gave me the code for everything that’s fair game, that everything belongs to everyone. For three or four years, all I listened to were folk standards. I went to sleep singing folk songs.”

So, he explained, the lyrics to all these songs informed his musical vocabulary and when it was his turn to write his own songs, what came out, he thought, was because of what had come before.

“If you sang “John Henry” as many times as me – “John Henry was a steel-driving man / Died with a hammer in his hand / John Henry said a man ain’t nothin’ but a man / Before I let that steam drill drive me down / I’ll die with that hammer in my hand.” If you had sung that song as many times as I did, you’d have written “How many roads must a man walk down?” too.”

From there, he walked through old songs – “Key To The Highway” – then his “Highway 61 Revisited.” And down the list he went, an old song, then his own for “Boots Of Spanish Leather,” and “Maggie’s Farm” and “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.”

To Dylan, and probably nobody else, he saw a progression, carrying on, taking part in a tradition.

“All these songs are connected. Don’t be fooled,” he said. “I just opened up a different door in a different kind of way. It’s just different, saying the same thing. I didn’t think it was anything out of the ordinary. I didn’t think I was doing anything different. I thought I was just extending the line.”

From there, having explained to his satisfaction where these songs came from, he turned to the reaction to them and how somehow, they seemed divisive. And now, having achieved what he has, he remembered those long-ago hurts and to our surprise, this most private man decided to share them.

“Leiber and Stoller didn’t think much of my songs. They didn’t like ’em, but Doc Pomus did. That was all right that they didn’t like ’em, because I never liked their songs either. “Yakety yak, don’t talk back.” “Charlie Brown is a clown,” “Baby I’m a hog for you.” Novelty songs, not serious. Doc’s songs, they were better. “This Magic Moment.” “Lonely Avenue.” “Save the Last Dance for Me.” Those songs broke my heart. I figured I’d rather have his blessings any day than theirs.”

Boom. And he kept going, taking aim at Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun.

“Ahmet Ertegun didn’t think much of my songs, but Sam Phillips did. Ahmet founded Atlantic Records. He produced some great records: Ray Charles, Ruth Brown, LaVerne Baker, just to name a few. There were some great records in there, no doubt about it. But Sam Phillips, he recorded Elvis and Jerry Lee, Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash. Radical artists that shook the very essence of humanity. Revolutionaries with vision and foresight. Fearless and sensitive at the same time. Revolution in style and scope. Radical to the bone. Songs that cut you to the bone. Renegades in all degrees, doing songs that would never decay, and still resound to this day. Oh, yeah, I’d rather have Sam Phillips’ blessing any day.”

Perhaps the most surprising rebuke came for country singer Merle Haggard, who Dylan had actually toured with just a few years earlier.

“Merle Haggard didn’t think much of my songs, but Buck Owens did, and Buck even recorded some of my early songs. Now I admire Merle – “Mama Tried,” “Tonight The Bottle Let Me Down,” “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive.” I understand all that but I can’t imagine Waylon Jennings singing “The Bottle Let Me Down.” I love Merle but he’s not Buck. Buck Owens wrote “Together Again” and that song trumps anything that ever came out of Bakersfield.”

A few days after the speech and the subsequent blowback, Dylan explained a little more about his Haggard comments.

“What I was talking about happened a long time ago, maybe in the late sixties,” he said. “Merle had that song out called “Fighting Side of Me” and I’d seen an interview with him where he was going on about hippies and Dylan and the counter culture, and it kind of stuck in my mind and hurt, lumping me in with everything he didn’t like.”

“But, of course, times have changed and he’s changed, too. If hippies were around today, he’d be on their side and he himself is part of the counterculture … so yeah, things change. I’ve toured with him and have the highest regard for him, his songs, his talent – I even wanted him to play fiddle on one of my records and his Jimmie Rodgers tribute album is one of my favorites that I never get tired of listening to... Back then, though, Buck and Merle were closely associated... Buck reached out to me in those days, and lifted up my spirits when I was down, I mean really down – oppressed on all sides and down and that meant a lot, that Buck did that. I wasn’t dissing Merle at all, we were different people back then. Those were difficult times. It was more intense back then and things hit harder and hurt more.”

Finally, he talked about the critics, those who suggest his singing is, at times, questionable. As he delivered these lines, it seemed as if he’d been hanging onto these ideas for quite a while and was enjoying the chance to vent.

“Critics have always been on my tail since day one,” he said, drawing a cheer. “Seems like they’ve always given me special treatment. Some of the music critics say I can’t sing. I croak. Sound like a frog. Why don’t these same critics say similar things about Tom Waits? They say my voice is shot. That I have no voice. Why don’t they say those things about Leonard Cohen? Why do I get special treatment? Critics say I can’t carry a tune and I talk my way through a song. Really? I’ve never heard that said about Lou Reed. Why does he get to go scot-free? What have I done to deserve this special treatment? Why me, Lord?

“No vocal range? When’s the last time you’ve read that about Dr. John? You’ve never read that about Dr John. Why don’t they say that about him? Slur my words, got no diction. You have to wonder if these critics have ever heard Charley Patton or Son House or Wolf. Talk about slurred words and no diction. Why don’t they say those same things about them?”

Perhaps the most surprising comment was his description of the performance of the National Anthem that he’d seen at a Floyd Mayweather fight.

“Critics say I mangle my melodies, render my songs unrecognizable. Oh, really? Let me tell you something. I was at a boxing match a few years ago seeing Floyd Mayweather fight a Puerto Rican guy. And the Puerto Rican national anthem, somebody sang it and it was beautiful. It was heartfelt and it was moving. After that it was time for our national anthem. And a very popular soul-singing sister (Marsha Ambrosius) was chosen to sing. She sang every note that exists, and some that don’t exist. Talk about mangling a melody. You take a one-syllable word and make it last for 15 minutes? She was doing vocal gymnastics like she was a trapeze act. But to me it was not funny.”

Later, he took a pretty good shot at country singer Tom T. Hall, a Nashville product, who, Dylan explained, was somewhat close-minded about lyricists like James Taylor (and him) who didn’t write Nashville-style country songs.

“Now some might say Tom is a great songwriter. I’m not going to doubt that. At the time he was doing this interview, I was actually listening to a song of his on the radio. It was called “I Love.” I was listening to it in a recording studio, and he was talking about all the things he loves, an everyman kind of song, trying to connect with people. Trying to make you think that he’s just like you and you’re just like him. We all love the same things, and we’re all in this together. Tom loves little baby ducks, slow-moving trains and rain. He loves old pickup trucks and little country streams. Sleep without dreams. Bourbon in a glass. Coffee in a cup. Tomatoes on the vine, and onions.

“Now listen, I’m not ever going to disparage another songwriter. I’m not going to do that. I’m not saying it’s a bad song. I’m just saying it might be a little overcooked.”

As he wound down, he found a little bit of wry Dylanesque humor. Don’t believe him when he says he never reads reviews or anything written about him. He reads everything! To wit: “Critics have said that I’ve made a career out of confounding expectations. Really? Because that’s all I do? That’s how I think about it. Confounding expectations. Like I stay up late at night thinking about how to do it. “What do you do for a living, man?” “Oh, I confound expectations.” You’re going to get a job, the man says, “What do you do?” “Oh, confound expectations. And the man says, “Well, we already have that spot filled. Call us back. Or don’t call us, we’ll call you.” Confounding expectations. I don’t even know what that means or who has time for it. Why me, Lord? My work confounds them obviously, but I really don’t know how I do it.”

For a guy who has always chosen where and when he makes his comments, it was quite an evening, quite a speech.

This is Edition Three of a book I’ve been doing on Uncle Bob since 2005. It’s on Amazon if you’re interested. Happy birthday, Bob!

What an amazing insight into this man I agree with Chuck that he is a great poet. Tangled up in blue is a favorite of mine. Thank you, John!

I could never understand why Dylan was ever criticized for his singing. He was never a singer. He was always a poet. And a great one.