Did Dickens recognize his breakthrough?

"Bleak House" opening still seems remarkable 170 years later

Can we spot a breakthrough when it happens? Can a writer? Does some little bell go off in your head, some tingling at the ends of your fingers?

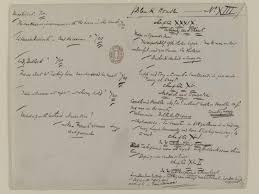

When Charles Dickens sat down to start “Bleak House,” his ninth novel, sometime in 1851 on some cool English morning, did he simply say the hell with convention, structure and formality, the way he and pretty much every other Victorian author wrote up to that point?

Sitting in his study in Tavistock House in central London that day, did he think to himself? “The hell with sentences, paragraphs. Going from A to B to C. I’m going to let the words, the images come as they might. My readers will trust me. They will understand.”

Now, Dickens already had considerable literary successes with “Oliver Twist,” and “Nicholas Nickleby” — novels which he serialized AND wrote simultaneously (!) Think about that for a moment. Writing TWO novels at the same time, publishing something each month in magazines that had all of London reading him. He was phenomenally popular and, as we can see, prolific.

Then he wrote “David Copperfield” so it was clear, Charles Dickens had some serious game. But living in Victorian England, how much nerve did the guy have? What sort of artistic courage?

Maybe it’s me, but re-reading the extraordinary opening of this novel now, in 2025, it does not seem like something jotted down in some English parlor 172 years ago.

So perhaps Dickens was feeling his oats when he picked up his goosequill pen that morning, surveyed that blank piece of paper that lay before him on his desk, dipped the tip in his pot of ink and started to write…

Chapter 1 -- In Chancery

LONDON — Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather…

Michaelmas Term, which means autumn in London, OK. The weather is acting up. Got that. But the Lord Chancellor? So what if he’s sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Wouldn’t an editor have said, “Charlie, these aren’t complete sentences? Why is the Lord Chancellor mentioned here?

Dickens keeps going…

As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.

A what? A Megalosaurus? A dinosaur term coined in England in 1824 by William Buckland and what an image! No water, just mud and this 40-foot dinosaur waddling up the hill. Where’s he going with this? Are we going back in time? What kind of portrait of his city is he painting here? These are like notebook jottings.

Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun.

Snow-flakes going into mourning? The death of the sun? These are terrifying images, concepts, aren’t they for the start of a novel. Soot, mud, smoke, mud, could London be less appealing? Where is he going with this?

Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill-temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if the day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

Note the smart-ass humor at that last bit “accumulating at compound interest.” So much mud and mire you can’t tell a German Shepherd from a Collie. Horses are splashed in mud up to their blinkers (eyes). And people, some poor Londoners trying to walk in this crap “in a general infection (what a word choice!) of ill-temper, losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if the day ever broke)”

If the day EVER broke? Has England been stuck in night forever? And a person can’t even walk, tens of thousands were so mired in the mud tramped on by thousands, tens of thousands he said, — generations? — frankly unable to walk, losing their balance, what is he saying about where England is at this moment in history?

And if all that doesn’t do it for you — and remember, we still haven’t gotten to him bringing in the Lord Chancellor seven words into his text — now Dickens brings in his last natural element, one that foreshadows and colors and shapes what this whole novel will be about- — what muddy, grimy ill-tempered England is perhaps foolishly attempting to peer through, particularly when it comes to the concepts of justice and fairness. It is as if the natural world around London is conspiring against those things.

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards, and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little apprentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.

It’s like a panoramic view of all he can see and imagine in old London. Again, this is written with a goosequill pen some 170-some years ago! He can’t stop.

Gas looming through the fog in divers places in the streets, much as the sun may, from the spongey fields, be seen to loom by husbandman and ploughboy. Most of the shops lighted two hours before their time as the gas seems to know, for it has a haggard and unwilling look.

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation, Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.”

Finally, we might even say, triumphantly, Charles Dickens gets to the character he mentioned in the opening sentence, or more correctly, his “note.” We meet The Lord High Chancellor in the High Court of Chancery, that court, which you might want to put quotes around it, for that “court” will become the ultimate topic of what some feel is his greatest novel, “Bleak House” where he lays out what that “court” had become.

Dickens gives the world — and Londoners — a harrowing look at the corruption, the injustice, the murkiness of the English court system, preying on the weak and unfortunate. A court system that had little to do with justice and fairness.

It is a work that so inspired the famed Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov, a novel he taught at Wellesley College in 1941 that he wrote: “We just surrender ourselves to Dickens’s voice—that is all. . . All we have to do when reading Bleak House is relax and let our spines take over. Although we read with our minds, the seat of artistic delight is between the shoulder blades. That little shiver behind is quite certainly the highest form of emotion that humanity has attained when evolving pure art and pure science.”

Re-reading this opening now, all these years later, it does not seem dated one bit. You wonder if Dickens, lifting that goosequill pen off the page late that morning, realized what he had done?

As Charlie Tyson wrote in The Atlantic a while back: “In that year he began writing Bleak House in which he sought to capture, through formal and stylistic experimentation, the density and complexity of 19th-century London. The story unearths hidden connections among far-flung people (dancing teachers, detectives, street sweepers). A novel of networks, Bleak House offered its readers a powerful model for thinking about urban life: a new kind of literature for a new kind of world.”

A new kind of literature for a new kind of world. Are we embarking, right at this moment, in a new kind of world, one that terrifies and challenges and confounds us, almost on a daily basis?

Does the painstaking, kaleidoscopic manner in which Dickens’ opened “Bleak House” hold meaning for us in the USA at this moment?

Who would dare say it doesn’t?

Thank you! So very kind. 🙏

How wonderful to wake up in the morning, fail to keep my intention not to check my phone while still in bed, and be rewarded with a delightful post on Dickens, Bleak House, how to begin a novel, and, of course, fog.