Figuring out Bruce Springsteen ain't easy

Does Steven Hyden's "There Was Nothing You Could Do" dumb him down?

Attempting a book-length look at the career and some might say the apotheosis of Bruce Springsteen is a challenging assignment for any writer. Steven Hyden is certainly an established music literati, having done books on Pearl Jam, Radiohead, The Black Crowes and written about all sorts of popular music for a long time.

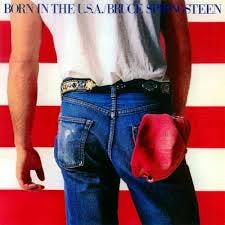

His latest book, “There Was Nothing You Could Do” is an in-depth look at Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The USA” album and what has followed in his long career, including the recent ticket hassles on this current tour.

Previously, Hyden wrote about bands, and not ones that you’d say had any truly major impact on America and its citizens. Not that they weren’t successful or accomplished. But they weren’t icons.

At this point, Bruce Springsteen is. And writing as someone who’s written three editions of a book on another icon (Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography — available on Amazon!), trying to explain how a phenomenon like Springsteen actually happened and what he means or even better, why his work matters, well, that’s a mighty task.

Unlike Dylan, Springsteen has opened a lot of doors to his work and life, writing an open, deeply personal book, “Born To Run,” and performing 236 one-man shows that seemed equal parts performance and confession, not to mention this and previous worldwide tours, the Apple TV special “Letter To You,” all these interviews, unannounced guest spots, why, you never know where he’ll show up.

With all this information out there — and him still touring — attempting to assess the impact or merit of his career is a daunting task. Why any artist makes it big or endures over a long stretch through multiple albums is always intriguing but not so easy to explain or categorize. Particularly an album like “Born In The USA" one that brought Springsteen to such a wider audience.

The releases of Springsteen’s first four albums, stretched over a five-year run (“Greetings from Asbury Park” and “The Wild, The Innocent, The E Street Shuffle” both came out in the same year -1973) were each so very different from its predecessor that once “Born In The USA” rumbled out some 11 years after his album debut, Springsteen’s extraordinary live shows and burgeoning reputation had built such a following that when the record exploded over the airwaves in 1984, nobody should have been all that surprised. Album after album, tour after tour, he seemed to be building up to something.

“Born In The USA’s” startling success — one of the top 25 best-selling records of all time, album sales of at least 22 million, seven Top Ten singles, five MTV videos — was so monumental that it made people stop and take stock. When an artist achieves almost universal acclaim, it’s tempting to try to figure out what exactly happened.

Hyden’s “There Was Nothing You Could Do, Bruce Springsteen’s “Born In The USA” and The End Of The Heartland” boldly tries do just that. When a record goes over like Bruce’s did, when that many people evidently agree on something, it’s worth examining. Though Hyden gives it the old college try, I’m not sure he quite grasps what some would say is the essence of Springsteen’s music.

“By the time “Born In The USA” was released six years later, “ he writes, “he had discovered a more effective commercial formula; he still wrote intense and alienated songs, but he made them sound happy.

“On paper, it seems simple. But even in practice, it’s a tricky formula. Not everyone can pull it off…this skill also caused many of his most popular tunes to be taken the wrong way.”

Hmmm. “Born In The USA” certainly was seen by the likes of George Will and Ronald Reagan as a joyous celebration of America when to me, that was only part of what the song was about. Not the most important part, either.

But when Hyden contends “Of the seven Top Ten singles released…at least six of them can be described at happy-sounding sad songs. ‘Dancing In The Dark’ is an infectious synth-pop tun about self-hatred…” “Glory Days” uncovers the melancholy of middle age at the heart of simpleminded nostalgia and pits it against music that openly panders to nostalgists in love with old-fashioned rock…” and so on, I disagree.

I don’t see “Dancing In The Dark” as about self-hatred as much as I hear it as a song about a writer (to which I can relate) who’s frustrated by his repeated, determined attempts to try to make his art as good as it can be, which sounds EXACTLY like where Springsteen was writing this album.

(Remember that after recording dozens and dozens of tracks in the studio, Springsteen’s manager Jon Landau told Bruce he didn’t hear a single and asked him to go home and write it. First, Bruce told him to go do it, then turned in “Dancing In The Dark” - which was exactly what Landau was looking for. And he was right!)

To me, the song shows that the singer/writer/narrator, recognizing that in spite of all his well-intentioned hard work, like Jack Nicholson warns in “The Shining” - “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” — the guy correctly recognizes he needs a little spark, a human connection to make him feel whole, “even if it’s just dancing in the dark” and not exactly sex.

So I can’t quite make the leap to self-hatred. Bruce’s writing, I don’t think, is that easily classified as “sad” but “sounding happy.” To me, that dumbs the whole thing down. Judging from what I’ve read and heard (Tracks!) Springsteen’s writing and song-selecting process is way more selective and from all accounts, way more exhaustive than that. To imply that merely by making a “sad song sound happy” is going to sell millions of albums, I think it cheapens Springsteen’s achievement and undercuts his genuine impact with the listener.

Similarly, on “Glory Days,” I don’t think nostalgia has to be “simpleminded” or that middle age is necessarily “melancholy.” For many of us up there in years — Hyden is 47, just a pup — looking back on our “Glory Days” doesn’t make us sad, on the contrary, it can bring back a time when we had the world — or so we thought — by the short and curlies. And what a fun time, an exciting time, it was. And why the hell not relive it?

Sure, Bruce notices that the ol’ high school baseball star pitcher maybe dwells on those days a little more than is recommended but doesn’t the fact that Bruce DOES notice that (it was pretty obvious, after all) mean that he won’t fall for that?

Except, in the last verse, he recognizes that trait in himself, and, perhaps, in all humanity, if you want to take the big picture view. And the joyous music that supports these lyrics, how the song never wants to end — you hear Bruce tell the band “Keep on goin’” as they play it out — only serves to make the listener remember his or her own “glory days” and NOT REGRET IT FOR A SPLIT-SECOND. If Hyden had talked about universal themes, how Springsteen’s songs on this record in particular, seemed to address themes we all can relate or connect to, which might be a better way to explain the deeper connection with his audience that Bruce has rather than suggesting it’s writing sad songs that sound happy.

And yeah, with “Born In The USA” people don’t necessarily misinterpret the message of the song as much as they hear what they want to hear. The irresistible chorus, “Born in the USA” applies, well, to just about all of us. Most of us ARE proud to be “Born in the USA” for all it’s faults.

Yet I remember seeing Bruce perform the song live on the Amnesty International Tour in Buenos Aires, Argentina and the Argentine people belting out the chorus, too. So it wasn’t just about patriotism, was it?

Whether he consciously tried for this complexity or not, you can argue that magically, through Bruce responding to the way Max Weinberg made the drums sound like bombs, that he was able to somehow imply the complexity of being an American, being proud of this country while at the same time, appalled at how we treated our Vietnam vets (and maybe all people who “end up like a dog that’s been beat too much.’) Maybe in this mystical song, Springsteen found a way to include both elements, the dynamic, unrelenting power and explosive energy of the song, the pride and strength of being an American as well as the pain and heartache and disappointment of some of us who went through this war and witnessed its aftermath. Maybe what he tapped into — consciously or unconsciously — there was such raw power there, Bruce has to resort to a blood-curdling scream near the song’s dramatic finish with set things right.

To me, writing about this song for my classes, I could sense WHY war continues to be so appealing to men, how that martial riff plays in your head and won’t stop. Here’s what I thought Bruce poured into the song.

BORN IN THE USA – Bruce Springsteen

You can see the soldiers marching off to war. The drums, mixed high and loud, are like rifle shots. The martial, repetitive, stirring tune, propelled across the piano keyboard again and again and again…the riff that gets between your ears and won’t let go. Yet amidst this grand and powerful song, emerges a lyric that features, perhaps hangs on, a scream. It is a song that to me, explains the allure of war, of soldiers united in a single cause, going off to triumph and at the same time, the lyric expresses the horrors, the disillusionment, the sense of betrayal soldiers feel when they return home. We do not know, feel what they have felt on the battlefield so when they come back to our quiet lives and try and fit in, they are the bump under the blanket, the rock in the road, their emotions and hearts and brains have been so transformed by that horrific experience, they are no longer one of us. But long to be. And that relentless, marching chorus and irresistible tune keeps surging, surging, luring us in. Where are we fighting today? Ukraine? Iran? Afghanistan. Yesterday? Germany, France, Vietnam, Korea. Where will it be tomorrow?

Hyden offers a different take. He kind of cops out, really. He suggests “Born In The USA” “is a song designed to be heard in a multitude of ways and only one of those interpretations aligns with Bruce’s original intent.” Which is true but…

Maybe Bruce, acting on an artistic instinct that had carried him this far without a false step (other than maybe “Lucky Town” and “Human Touch”), didn’t necessarily UNDERSTAND his original intent; he’d written a precursor called “Vietnam” that hinted at where he was going.

But in the studio, when he heard Max Weinberg’s drums, and that martial riff with the whole band behind him on Take Two, he knew he had something special, something that had to come out, whether anybody – including him – would ever fully understand it. Weinberg said later that it was, hands down, the single-most exciting moment of his recording career. They were hitting something with the song and even if they couldn’t explain it, they knew it.

I do like that “There Was Nothing You Could Do” gets us reading and thinking and listening to Bruce Springsteen. But I would have to think twice about labeling his songs as “happy” or “sad.” There’s much more there, if you ask me. I think Bruce would tell you that, too.

As a lifelong Springsteen fan and frequent reader of Hyden’s stuff, I hated this book. A waste of time. You’re spot on here, and I’m gonna order your Dylan book right now, in appreciation.