Ranking writers can be dangerous sport. When an assortment of literary professors and critics - Wilkie Collins and Brander Matthews - got up on their high horse and proclaimed James Fenimore Cooper “the greatest artist in the domain of romantic fiction yet produced by America,” the withering response from one Samuel Langhorne Clemens/AKA Mark Twain has echoed down the halls of history.

“It seems to me that it was far from right for the Professor of English Literature in Yale, the Professor of English Literature in Columbia, and Wilkie Collins to deliver opinions on Cooper's literature without having read some of it.” Twain writes, cigar burning, you can sense the wry smile on his mustachioed kisser.

“It would have been much more decorous to keep silent and let persons talk who have read Cooper. Cooper's art has some defects. In one place in Deerslayer, and in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offences against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.”

Twain’s “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses” is an American classic. Would he have written it without the praise of those literary “experts”?

Some years ago, author Norman Mailer started a 100-year appreciation of “Huckleberry Finn” in the New York Times by triumphantly citing some embarrassingly bad/short-sighted reviews of eventual literary classics. Passing literary judgment on a writer during his time - even immediately afterwards - is risky stuff.

There will be those who say David Wills’ 545-page opus on the entire body of writing submitted by Hunter S. Thompson - “High White Notes” - takes his work way more seriously than Thompson ever did, but I’m not sure that’s fair. Thompson’s impact on journalism and political writing was, for a time, seismic.

What we don’t know and really won’t be able to tell for a while is how history will look back on what he offered us. Will we see him as the wildly creative, ball-busting, shoot-from-the-hip politically literate lizard who didn’t hesitate a whit launching vicious - often hilarious - attacks at Richard Nixon and other political figures? Or will be seen as the more or less equivalent of a Nathanael West, author of two acclaimed books (“Miss Lonelyheart” and “Day Of The Locust”) in the 1930’s but otherwise isn’t spoken about much these days.

It’s hard to know if this is an American thing or not. Ralph Waldo Emerson was a way more celebrated figure in his day than Henry David Thoreau. It’s Thoreau that’s been more read since. Herman Melville, who just had a birthday the other day, earned roughly $1,300 for “Moby Dick” or roughly $20 a page. It wasn’t until years after his death that the novel was recognized as the masterwork it is.

Thompson got his start as a more or less traditional insightful journalist, writing for the National Observer and doing free-lance work before his book on “Hell’s Angels” brought him to national prominence. When what he thought was a failed writing assignment for Scanlan’s Magazine, covering his hometown Kentucky Derby by desperately turning in wildly exaggerated, “Gonzo” sketches of denizens of Louisville, Kentucky misbehaving around the edges of the historic race instead of the kind of story he was expected to write, it was seen as a journalistic breakthrough.

The old journalistic axiom, “you’re NOT the story” was turned on its head by Thompson, who brought readers along on his half fictional/half real adventures with hotels, rental cars, the police, straight arrows, dimwits and assorted characters of questionable moral standing. Bob Dylan, a Thompson favorite, might have once sung “to live outside the lie you must be honest” and Thompson might have loved the song but not honored its content. That was undoubtedly true of his classic road trip saga “Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas” where Thompson’s adventures are/are not to be taken literally, I don’t think. With Hunter, you never know.

When reading his hilarious “Fear And Loathing At The Super Bowl” or “The Great Shark Hunt” or his political classic “Fear and Loathing On The Campaign Trail” - touted as the least accurate, most truthful book on the 1972 Presidential race, part of you is understandably shocked by he writes, says and does, part of you understands that much of this - how much? - is strictly for effect.

Once Thompson finds a home at Rolling Stone Magazine as their National Affairs editor, he covers the campaign in a way that no other journalist ever had - or would. A classic Thompson prank was him writing a press story claiming that Democratic candidate Edmund Muskie was taking this bizarre African drug Ibogaine simply because Thompson had read a medical brief discussing the drug’s after-effects and noticing that, in his mind, Muskie was showing those same symptoms.

The national media, afraid of being scooped by this Rolling Stone reporter, hopped on the story, only to find that Thompson had made it up. It’s fair to say they found it a lot less funny than did Rolling Stone readers.

Sadly, there was a price to pay for Thompson’s renegade, iconoclastic behavior. First, he was just about impossible to deal with, both as an employee and working with an editor, some of whom would break into tears, waiting for him to try to squeak work in on or past deadline. When it came to personal behavior or the lack of it, Thompson’s various substance issues, alcohol, cocaine and who knows what else, once he’d caught the eye of the nation, he couldn’t hold it. The last part of his career was spotty, erratic, and often uninspired.

Wills’ faithfully records the high points, the moments of “High White Notes” in his work, as well as delving into his actual writing style, a more detailed analysis that you are likely to find anywhere else. And it is comprehensive, to say the least. Wills laid an eye on everything Thompson wrote, the half-hearted “Hey Rube” columns he wrote towards the end, many other stories that fell way shy of the Thompson mid-70’s standard.

Happily, he did notice Thompson’s last true blast, his coverage of the Roxanne Pulitzer trial in Palm Beach, “A Dog Has Taken My Place.” It’s an insightful, funny read like vintage Thompson and looking at it once more, you’re sad to think how much alcohol and drugs took over his life and seemed to have such an impact on his later work. He might have done so much more.

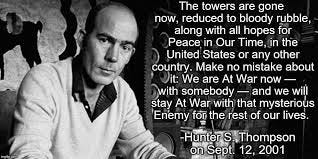

But every so often, he hit one out of the park. Look at this column excerpt, written after the 9/11 attack!

On the other hand, once you’ve “discovered” a new way to cover an event, once you’re strayed into “gonzo-style” coverage, should you repeat yourself until further notice? Thompson, one suspects, struggled with that concept and Wills’ hints at those late-career disappointments. As outrageous as Thompson was at his peak, by the end of “High White Notes” you can’t help but feel sad for the guy, something you suspect that would have truly pissed Thompson off.

How history will remember him and his work is hard to say for sure. It’s a safe bet that archivists years from now, stumbling upon his ground-breaking political coverage or “Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas” or some of his other inimitable work, they’re sure to break into a smile and ask “What was going on with THIS guy?” It’s a question you’ll ask too, finishing “High White Notes.”