"I'm Not There" - the Sequel

If Todd Haynes would add one more scene to his film, how about these?

With another Bob Dylan movie on the way with Timothy Chalamet as our hero, this seemed like an appropriate time to take another look at Todd Haynes’ extraordinary Dylan dream film - “I’m Not There,” a movie I really enjoyed when it came out, way back in 2007. Was it really that long ago?

What a delight to watch a film where the director really knew his Dylan. But has Bob’s personal story changed or maybe somehow deepened since it first appeared on screens across America? We had a pretty good idea of Bob’s life to that point, sure. But look what we’ve had since!

Together Through Life: Bob as a Tex-Mex composer, hiding out South of the Border down Mexico Way.

Christmas In The Heart: Bob goes Xmas-y. With a wig???

Tempest: Not wanting anybody to make any assumptions about his FINAL statement, Bob pointed out that Shakespeare’s final play was actually called “THE Tempest. It’s a different title.” he told us. OH. PARDON US.

Shadows In The Night: Though no one asks him to, Bob tries out the American Songbook

Fallen Angels: Though no one really asks him to, Bob insists on continuing to try out the American Songbook

Triplicate: Not really sure who he was recording this for — other than himself —Bob won’t stop trying out the American Songbook

Rough and Rowdy Ways — He’s back with HIS own songs. Hallelujah!

and this is not counting…

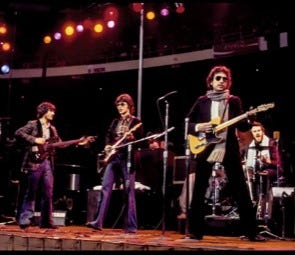

The 36-CD set of the entire 1966 World Tour featuring Bob and The Hawks (later The Band) in their loudest, wildest, rudest conflagration. Makes “Before The Flood” sound like choir practice

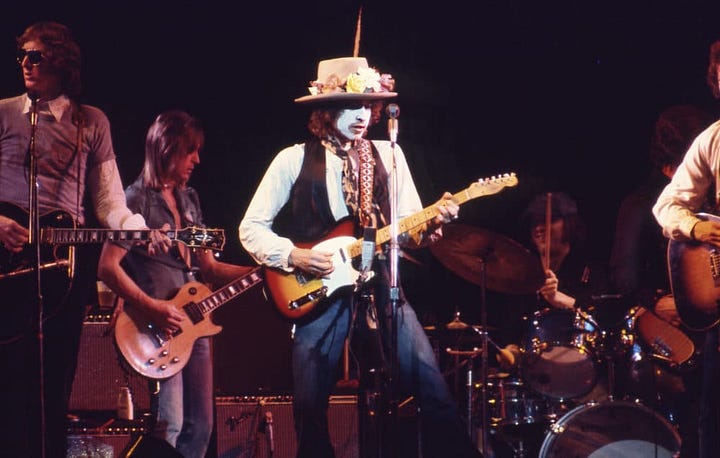

The 14-CD set from The Rolling Thunder Revue - Bob having fun on stage, even actually Bryan Ferry-izing his own “Hard Rain’s A’ Gonna Fall”

The 4-CD complete Budokan set for those who like flute with their “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

The 6-CD Complete Basement Tapes Bootleg Series, fleshing out Bob’s Basement Babblings (I say that affectionately…they are wonderful)

The 6-CD “Blood On The Tracks” outtakes - more raw bleeding Bob

The 5-CD “Fragments” outtakes from “Time Out Of Mind” before Daniel Lanois “improved” them. (No slam on Danny. “Time Out Of Mind” - as released - was awesome. And is STILL awesome, unlike, say, “Oh Mercy” which doesn’t quite seem to have lasted in quite the same way. “Series Of Dreams” woulda helped.

There are a bunch of other Bootleg Series releases, books, speeches and other arcana that has leaked out in the intervening 17 years.

That weird Shadow Kingdom “live” performance that looked more like an ad for the National Tobacco Institute. It featured Bob and the band “miming” to his pre-recorded songs for an “exclusive” streaming special.

And uh, THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR LITERATURE! Probably worth mentioning.

So.. while I really enjoyed Haynes’ film and he did a marvelous job closing the film, leaving Bob with us in the middle of one of those wonderfully extemporaneous harmonica solos that sometimes he’d tack onto the end of “Mr. Tambourine Man,” neither Haynes nor Dylan could have known there was so much more to go. At 83, he’s still touring and heading back to the Royal Albert Hall, the scene of his earlier 1966 triumphs in October.

If Haynes was going to add an epilogue to his film or a sequel, here’s a few scenes to round out his portrait of the artist, now as an old man.

THE NOBEL WIN: Maybe a scene where somebody like Jeff Rosen, his brilliant, always-ahead-of-the-curve manager/advisor breaks the news to Bob that he’d won the Nobel Prize for Literature. For a couple really annoying weeks, he can’t get Bob to acknowledge the incredible honor, to even say “Thanks, Academy.” All of Sweden is in an uproar.

Rosen is left trying to figure out how to get him to respond. Finally, he calls him on his cell phone, something Bob hates. “Come on, Bob. How does it feel?” he asks. “I sang that already,” he says.

BOB ON BROADWAY: Let’s say for just one night, Bob hires a small theater and a film crew and puts on his own “Bob On Broadway.” He’d read all the Springsteen raves and hey, just to show that if he felt like it, he could do just as good or maybe even a better one-man show than The Boss, he gives it a go. The theater would be empty, maybe just Rosen or Daniel Lanois or maybe David Letterman, just for grins. “You know, I like Bruce,” he’d say, walking out on stage with his guitar and harmonica, opening the show. “Had to needle him with “Tweeter And The Monkey Man.” I’d heard he liked it.

“Bruce is a hard-working, clean-living guy, he really cares. Puts on a great show every time. He said one time that if you write a great song, it’s not a great song until you play it for someone.

“See, I don’t think that way. I have a different relationship with my audience. (Breaks into a wry Dylan laugh) But I do have an audience. Still. Not tonight but that’s my choice.

“I certainly wasn’t going to invite those clowns who pick apart my songs like they’re looking for the wishbone on a Thanksgiving turkey. Or when they went at my book. Like somebody wrote I stole sentences from Robert Louis Stevenson. Oh, yeah. I went for all the hits.”

Bob shakes his head. Then, at center stage, he’d start playing his classic songs on acoustic guitar, exactly as he originally wrote them — as if he could have done that all along. This constant “Can you guess what song THIS is?” stuff were just, you know, something to keep him from repeating himself.

After each song, he’d smile and nod and explain what he remembered about writing the song or maybe talking about his life and his motivation at the time, just like Bruce did. Holding all these secrets for all these years, why, it would be almost a confessional.

He’d do that for maybe seven, eight songs. Then, about halfway through “Visions Of Johanna,” he’d stop, look directly into the one camera and say, “You know, if I drain the mystery out of these songs, maybe I ought to just tell you — I wrote this one when I was missing Joan Baez taking showers with me.”

He’d look directly into the lens. “Does that clear it all up for ya?”

RECORDING ‘MURDER MOST FOUL’ -February 2020 - LOS ANGELES, STUDIO A — 3 A.M.

I’m not sure how Todd Haynes would catch this on film. But I wish he could try. Bob Dylan is sitting in a corner, scribbling on a sheaf of papers, a big stack of them. Approaching 79, there’s no possible way of counting how many words have come out of the ends of his fingers, or out of his mouth into microphones all over the world since he hitchhiked into New York City all those years ago. He’s written songs and poems and album notes and speeches and books, given hundreds of interviews and yet, he hasn’t run out of ‘em.

When Jeff Rosen got the call that Bob was ready to record again, the first such call he’d gotten in eight years, he knew something unusual was brewing. There was an urgency in Bob’s voice — he knew him as well as anybody could know him by now — that made him think Bob had something coming, something he just had to cut, something big.

He called Haynes, who still didn’t know if Bob had ever seen “I’m Not There.” If Rosen was calling him, he must have liked it. Told him where they would be tonight, to come by late, or early, however you want to talk about it. Rosen was expecting him any minute.

Meanwhile, standing in that antiseptic control room, watching that shaggy mess of hair hovered over a page out there in the studio, he could see Bob’s writing, small and spidery, watching him working on sheet after sheet as if he were on a deadline. Which, at 79, you could say he is. The FINAL deadline.

All of this hits Rosen while he’s standing there that this might be Bob Dylan’s official last album. He’s watching him writing his own new material for the first time in, geez, a long time and now, maybe it’s also for the last time.

For those in the Bob World, there was always so much Bob stuff to wade through, stuff that took years, even decades to come out. Columbia recorded so many things, stuff in the studio, too. But this, well, this was coming out of his hand NOW, right now.

Pianist/organist Benmont Tench, formerly of Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers, a friend of Bob’s for a good while, sits there quietly, watching and reading a newspaper from the other corner of the studio. It occurs to him, too that it’s been a while since Bob has written something new. Something original. Something, you know, he didn’t “borrow” from Robert Louis Stevenson. Haha.

Bob had showed him an article that someone sent him the other day and the two of them read it, quoting lines, laughing at just how silly that was. “Well, yeah, Dylan wrote a book but, you know, he stole some lines from Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, Mark Twain…”

“They don’t get you, do they, Bob?” Benmont asked him then, laughing. Dylan just shrugged.

Watching the feverish way Dylan wrote now, Benmont remembered hearing the “Tempest” record. That was like eight years ago. It had that John Lennon song on it and that long sea chantey thing about the Titanic. Nothing since. Nothing he knew about, anyway.

Tench had worked with Bob on his perennially underrated “Shot Of Love” record. That was all the way back in 1981, he remembered. Dylan was just coming out of his “Christian” period and was so excited about the record. When Tench heard that “Every Grain of Sand,” well…who writes songs like that these days?

Then there were the Dylan/Petty tours with him, all around the world. Those shows were fun, you never knew when Dylan would turn to the band and say “Let’s do “Lucky Old Sun”” or some old chestnut or old oddity. Just winging it. Man, he knows some songs.

He watched Dylan’s pen work on the page, not a word to a soul, just a total focus on what he had before him. Such a stack of papers, too. He smiled to himself. Here the old man is, at it once again. And judging from the sheaf of papers he has, this is no simple tune.

Dylan reaches around to scratch his back. He’s hunched over a little desk, pages spread out before him, scratching some words out, flipping the pages back and forth. It’s intense, he’s in mid-creation — again.

Tench nods, soft drink in his hand. Doesn’t speak. If Bob speaks to you, then you speak back. Otherwise, keep quiet.

One of the studio engineers comes over to Tench, leans down and whispers.

“Two pianos? And your organ?”

“That’s what Bob said,” he said softly, then shrugs.

“Really?” he asks, eyes raised.

Benmont gestures with his thumb to the other corner, where he can see Dylan’s scraggy hair, hanging over a page. It may seem as if Dylan is oblivious to the world at that moment but the real truth is, Bob Dylan is very much in tune WITH the world at that moment. The nasty cloud of COVID is hanging over the country, his country. All of America, it seems, are wearing masks. Is this a holdup or something?

There’s a TV on in the control room, some sort of Presidential Press Conference, closed caption on, where the President, this dyed-blonde, over-bronzed loudmouth, a moron, is telling people at one point to use bleach to clear the crap out of your lungs. Tench remembered there was some poor bastard in Arizona who actually took the drug this idiot recommended, something like chloroquine phosphate for fish tanks or something and he died. Nice job, Prez.

How many Presidents has Bob Dylan seen, Tench wonders? Truman? He remembered reading some quip from him.

“When I was a boy, Harry Truman was President,” Dylan said. “Who the hell would want to be Harry Truman?” He laughed out loud, the sound bouncing off the recording studio walls. Dylan stopped writing for moment, turned.

“Alan here yet?”

“Haven’t seen him,” Tench said.

Dylan nodded and turned back to his papers.

Tench looked back to the control room and saw a tall, older man, maybe mid-sixties, black jacket, short hair. The serious look of a musician.

“Must be him,” he said to himself, quietly getting up and walking out to the control room. Once the door closed softly behind him, he extended a hand. “Alan Pasqua,” he said, smiling, nodding, shaking Tench’s hand.

“He’s still writing?” he says, gesturing to the older man’s pen, still working over what seems like quite a little stack of paper.

“That’s our Bob.”

Pasqua laughed. “When did you start with him, with Petty? I worked with him back in 1978. Long time ago.”

“Street Legal”?” Tench asked. “Around then?”

Pasqua nodded. “Record sounded a lot better when we cut it.”

“Not since then?”

“Well, I did the music for his lecture.”

“Lecture? Did miss something?”

Pasqua laughs. “Some would say ‘Yes.’ When Bob won the Nobel, I think it was 2017 or so, he asked me to give him some piano music for background, to play beneath his lecture. You win the prize, you want the money, you give a lecture.”

“He did?” Tench said. “Bob asked you himself?”

“No. Not him,” Pasqua said. “His team. They asked me to send them thirty minutes of music for an undisclosed project. They gave me some direction. I was like ‘What am I doing here?’ They used the model of early Steve Allen.”

“I remember when Bob was on the Steve Allen Show,” Tench said. “I remember that. It was in one of those movies, “No Direction Home” or something. He was just a kid. Allen made Elvis sing to a fucking dog but Bob, he called “a genius.” Bob was just giggling. Then he did ‘Hattie Carroll” as if to prove it or something.”

Pasqua looked back out at the older man scribbling away.

“Well, they wanted piano musings that may seem slightly bluesy but not really,” he said. “You know what I mean. They’re not necessarily connected, but they’re not terribly random either. That was just enough for me to go on.

“So I said ‘I’ll send you three minutes of some stuff and tell me if I’m in the right direction.’ And it was. They said “Do the rest.” I asked “When do you need it?” You guessed it. “Tomorrow.”

Tench laughed and the two of them both watched Dylan squint at his tiny scrawls again. Then the door opened and Fiona Apple walked in, stunned look on her face.

“Uh, is this…?”

Tench and Pasqua looked at one another. “Of course.”

When Bob looked up and saw the three of them, he smiled and gestured to them all to come into the studio. The two pianos were side by side, Benmont’s organ beside them. Bob was holding his Martin guitar.

“Here,” he said, handing a sheaf of his lyrics to Pasqua, sort of the leader of the three.

Pasqua stood there, holding these lyrics, maybe the last batch of them anybody would ever see from his hand. They hadn’t been sung yet. They were warm to the touch from Bob’s hand.

They all chatted quietly for a bit, Bob smiling at Fiona, trying to get her to feel comfortable, maybe with an eye to a future generation. Benmont sat at his organ, waiting. He knew the drill. Just then, Todd Haynes showed up in the control room. Rosen motioned to the studio. “You need to see this,” he said, softly.

Bob walked over to Pasqua and spoke softly in his ear, so soft neither of the others could hear it. Then he pointed to Fiona and nodded. “Follow him,” he said. He glanced at Benmont who, of course, knew the drill.

And so “Murder Most Foul” began with a tinkling, gentle piano, then Bob’s warm, knowing, crisply pronounced words “It was a dark day in Dallas, ‘63…” phrases that floated over Pasqua’s gentle piano, creating a perfectly paced, gently swirling blanket of sound, highlighting Bob’s strong, confident, knowing voice. He had something to say here. He meant business, he was going to be heard.

He was not exactly singing, almost as if something this serious, this important, should not have been sung, but spoken as if prompted by a relentless memory, a series of disconnected pictures and sounds and images that kept coming and coming, the music was there to, you know, smooth it all over.

As Dylan yanked these lyrics and phrases from history, the music rolled by, Dylan speaking clearly and deliberately with only occasional inflections on the end of a phrase, or the odd word. Pasqua’s playing was quiet but persistent, empathetic, as if the words actually generated the music.

Launched into the song, it was as if Dylan was hypnotized himself by this propulsive, staggering array of images and titles, fleeting memories, pictures, even voices as the listener and the musicians were woven into a spell. There was piano, organ, Donnie Herron’s mournful violin blending perfectly with Pasqua’s gently insistent waves of sound. Fiona Apple’s notes here and there, filling in as the verses piled one on another, memories, images, phrases that came so fast, like film from a motion picture camera reeling out of control.

But it always was under control, Dylan’s poised, all-knowing delivery — how many songs had he written and sung all these years to get to this place, this moment, maybe for the last time. This beast of a song would surge forth like an undeniable river of words and phrases and images, a swirling pool before Bob’s always wide-open eyes as he scanned the years. Those gathered around him were somehow under his unflinching command, riding along with him on this magic carpet of Dylan-delivered and savored phrases, each of them feeling every word to the very tips of their fingers and the soles of their feet.

When it ended with Bob’s perfectly delivered “Play the Blood-Stained Banner,” Play “Murder Most Foul” there were stunned looks on everyone’s faces. It wasn’t so much a song as a incantation, a spell woven by the only man who could have written a song like that.

Haynes was silently weeping. “Thank you,” he said softly to Rosen. “I wouldn’t have been able to film that. Film wouldn’t hold a moment like that.”

A little later, after a playback, Pasqua leaned in toward Tench. He was almost trembling.

“The whole thing is in free time,” he whispered. “There’s no tempo or anything.” And yet, it held together, almost by magnetic force. Bob spotted Pasqua talking to Tench and turned towards him, his often inscrutable face this time, wide open, eyes curious.

“Bob, this is like “A Love Supreme,” “Pasqua said, referring to the great John Coltrane’s unapproachable burst of untethered jazz lines from so many years before.

Dylan just looked at Pasqua, then Tench, then back at the control room. There were no more words available to anyone. When each of them drove home, they shut the radio off. There was still sound in their ears.

A few days later, the news still full of COVID fear and sadness, the President of no use, Bob Dylan gave the OK to release his 17-minute song, late on a Friday night, with the vaguest of messages on Twitter.

“Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years. This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you. Bob Dylan”

It was a voice, maybe THE VOICE America needed to hear. For the first time in a while. A long while. This familiar, crisp voice, rough, weathered, careful, caring. After all this time. “Stay safe.”

Midnight on a Friday late in March. (Sounds like the intro to his ‘Theme Time Radio’…) A scared, lonesome, suddenly all too vulnerable world, frozen with fear of this shocking pandemic, unable to find truth anywhere, certainly not from our leaders or the television set, and this voice, familiar, rough, speaking directly to you, it seemed, coming right out of the speakers on your radio.

Didn’t he once joke with John Lennon about being ahead of the curve — something like “Yeah, I’m ahead. But only by about 15 minutes.” A joke, then. This was no joke now. Was it COVID? Did his artist’s antennae tell him this was the time?

What if it flopped? It was a fair question, wondering if the world would still want to lend an ear to this relic? Dylan had made a career, at times almost a spectacle of NOT TALKING or RESPONDING. So why now?

Looking back, four years ago, the first original song Bob Dylan writes in, what, eight years is an unsettling, surprising 17-minute meditation on the still jolting death of John F. Kennedy. That took some nerve, didn’t it?

Maybe that was what Rosen sensed in Bob’s voice. His first song since being awarded the Nobel Prize is “Highlands” long, “Desolation Row” long. Did he feel as if he had to prove something? Or did he feel as if he, if somebody had to to say something at this critical, empty time? Speak to the country, the nation. To tell them to stay safe. That Bob was still here, on the lookout.

It worked. This 17-minute monolith of a song went to No. 1. Radio stations were playing the whole thing! His first No. 1. At age 79!

In these haunted, difficult times who would have thought Bob Dylan’s voice would be the one to break the silence, connect with so many people, people who, you’d bet hadn’t listened to a new Bob Dylan song in years, maybe decades.

Bob has never said why he wrote it. He may not know. Or better yet, he may not even know why he chose to release it then, in such a mysterious, unexpected, unprecedented way. Or why it worked.

Certainly, his was a voice that sounded like it’d been through the wars and was still here. With us. FOR us. Maybe, somehow, we needed that and after all these ducks and dodges and disguises and unanswered questions, he sensed we needed him. So he spoke up.

Like Bruce Springsteen said. “The father of my country.”

(Special thanks to Ray Padgett and Andy Greene for their stories - which spurred my imagination — and I hope, yours. My third edition of “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography 1961-2022” is available on Amazon.