Introducing Bob Dylan's Vol. 3

Dylan's in the air now - "A Complete Unknown" opens on Christmas Day

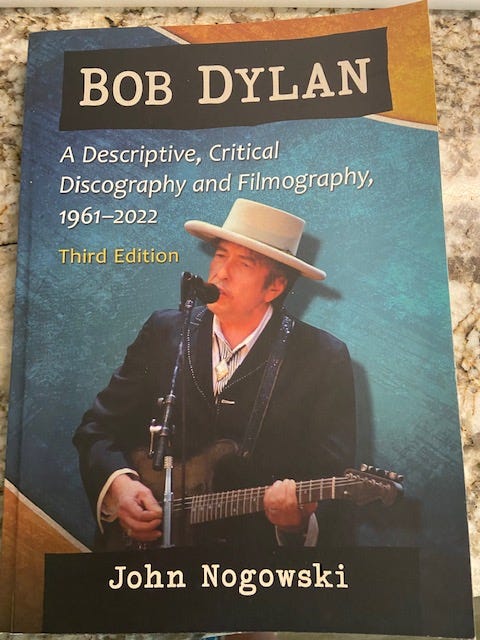

EDITOR’S NOTE: With Christmas just a couple weeks away and so much excitement about the new Bob Dylan movie “A Complete Unknown” hitting theaters on Christmas Day — Bob has even said how much he likes it! - a friend of mine suggested sharing a chapter from my recent book: “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography” on my Substack, which might help Dylan fans out their fill out their shopping list. It’s available locally at Barnes & Noble and Hearth & Soul, if you’re interested.

My book is the third edition of a continuing series I’ve done for McFarland and Co., since 2005. Edition Three includes the two previous editions is 352 pages long and covers everything Bob has done all the way through his last studio album, “Rough and Rowdy Ways.” It also includes a look at his films, his books, TV appearances, bootleg albums and an annotated bibliography of a whole bunch of other writer’s books about Bob Dylan.

If you’re a Dylan fan and want to gear up for the movie, the book is also available of course, on Amazon. Can’t wait to see “A Complete Unknown.” In the meantime, happy reading!

BOB DYLAN REVISITED (My Introduction to Edition Three)

You hear this familiar, crisp voice, rough, weathered, careful, ring out across the music as if it had been trapped. Almost as if you can watch the words tumble out…

It’s midnight on a Friday late in March. (Sounds like the intro to Theme Time Radio…) A scared, lonesome, suddenly all too vulnerable world is frozen with fear of this shocking pandemic. Unable to find truth anywhere, certainly not from our leaders or the television set, it’s almost like when schoolkids were taught how to duck under their desks, fearing that Soviet attack that meant the end of the world. Coronavirus is everywhere at once, it seems.

Suddenly, there’s something new posted on Twitter. What? A NEW Bob Dylan song? Would the world lend an ear to this relic? Quietly, Bob Dylan slips out “Murder Most Foul,” an unsettling, surprising 17-minute meditation on the still jolting death of John F. Kennedy, Dylan’s first original tune since being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. And it goes to No.1! His first! Would there be an album to follow? What was happening?

It’d been eight years since anybody had heard much of anything new from Bob. Until the pandemic, there had been plenty of noise from the cranky old man; those never-ending tours with often unrecognizable renditions of old songs and somewhat raggedy cover versions of tunes from the great American Songbook as done mostly by Frank Sinatra. Nothing really “new.” As in not sung before.

So now, here comes this 17-minute monolith of a song. In these haunted, difficult times who would have thought Bob Dylan’s voice would be the one to break the silence? Wasn’t the guy in his 80’s? Wasn’t he done writing?

Nope. There it was on Twitter that Friday night, no warning: “Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for your support and loyalty across the years. This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant, and may God be with you. Bob Dylan”

Bob saying thanks. Cool. Bob writing again!

With the surprising success of “Murder Most Foul” going to No. 1 on the Billboard Charts, evidently many people found hearing from him comforting, something we didn’t know we needed. Here was a voice that sounded like it’d been through the wars and was still here. With us. FOR us.

Now you know if Bob read that, you could see his expression. The scowl. Or the stare. Or he’d pull that everlasting hoodie up further. Well, Bob Dylan can sound as indignant as he wants about being tabbed “the voice of a generation.” But if he’s that upset about it, then maybe he ought to stop acting like “the voice of a generation.”

You can’t listen to any number of the songs he’s shared for decades now, from “Ain’t Talkin’” to “Things Have Changed” to “Murder Most Foul,” without thinking that this is a guy writing from a place, a platform where nobody else is. And he thinks he has something important to say. And does. Even now, at 79.

He can sing “I used to care, but things have changed” all he wants and add in all the other ducks and dodges that’ve alternately delighted and frustrated a sea of followers in his amazingly long run. But if you’ve paid any attention at all – which I would surmise you have, since you’re reading this – Bob Dylan feels a responsibility, a duty, a calling, an urge, whatever you want to call it, to share his feelings, his experience, his insight on recordings from time to time. Even now.

If you’ve followed his career, the highs and lows, the long silences and mystifying turns – 3 albums of crooner songs released all at once?; a Christmas album? Self-Portrait? ( I could go on). But the moment that surprises and seems to jump out at you on “Rough And Rowdy Ways,” his 39th album, is when you hear him sing, with as much passion as the old geezer can muster -“I’ve made up my mind to give myself to you.”

Just for an instant, after all the years and guises and misdirection and sarcasm and subterfuge, it’s as if 79-year-old Bob Dylan felt now, right now, would be the perfect time to sneak in the truth. He’s made up his mind to give himself to us. To explain, finally, why he’s kept after it all these years. Why it still matters to him – and to us.

Everything, of course, is done strictly on his terms – as always. He’s certainly not doing any of this for free. The overflow of archival material that has flowed from the great Columbia vault over the last dozen years; pricey projects, too, show he (and his record company) are not above making a dollar or two. The never-ending tours (3,891 concerts according to Concertarchives.com) – halted only by the pandemic (God: How do we stop this Dylan character? He’s almost 80!) are certainly supplementing his income, child support, alimony payments, etc.

Bob Dylan isn’t about to give us this grand explanation of his artistic mission. Maybe he doesn’t have to. Consider the one interview he granted before this album release was his chat with historian Douglas Brinkley. It appeared in the New York Times just as “Rough And Rowdy Ways” came out. The article opens: “A few years ago, sitting beneath shade trees in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., I had a two-hour discussion with Bob Dylan that touched on Malcolm X, the French Revolution, Franklin Roosevelt and World War II. At one juncture, he asked me what I knew about the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864. When I answered, “Not enough,” he got up from his folding chair, climbed into his tour bus, and came back five minutes later with photocopies describing how U.S. troops had butchered hundreds of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapahoe in southeastern Colorado.”

Ok, so at 77 (then), Bob Dylan found himself teaching one of American’s top historians about another incident of American injustice. Why? Maybe it’s a naïve suggestion, one Greil Marcus or Robert Christgau would laugh at, but maybe he’s made up his mind to give himself to us, to have that voice, his say. Decided that long ago, actually. Which, if you think about it, would explain these endless tours, traveling the world like an apostle and his insistence on keeping active; welding?, recording silky Sinatra songs with a voice gently described as ravaged, selling hootch, his paintings, his giving a one-man concert performance, going to the circus with Jimmy Fallon… living! This is what he does and will do until he dies.

That thought, about Dylan’s relentless - or maybe unrelenting is a better phrase - artistic commitment, conscience, calling, crusade…there’s not an exact word for it, occurred to me a few years ago as I watched “I’m Not There,” Todd Haynes’ imaginative film portrait of the many lives of Bob Dylan. I loved the movie and the way it wove the many lives of Bob Dylan – something Daniel Lanois talked about – into a narrative that was a lot like growing up listening to his work; the two of us, me and Uncle Bob to steal an album title, going together through life.

There were so many electric moments of real connection in that film – Haynes knows his Dylan - the machine guns at Newport, the Judas moment, the Beatles coming to the swank party with him, high as kites on Bob-introduced weed. But the moment that grabbed me was Richard Gere’s part, a moment that at first, didn’t seem to fit at all, a moment Hollywood producers didn’t think worked. They had asked him to remove it, which Haynes, in a Dylanesque move, refused.

Gere is playing a sort of modern-day Billy The Kid who awakens from what seems like a Rip Van Winkle-ish sleep (think of Bob’s ‘silent’ period after ‘Blonde On Blonde’ and before ‘John Wesley Harding.”) and he wanders into a town called Riddle Township and discovers all these Basement Tapes characters stuck in some sort of a crisis. As the scene opens, a thief has run off with something and Gere finds himself as part of a procession of people walking into town, just another pilgrim on the march of life. Everyone, it seems, is on the move. As Haynes holds a long shot of Billy, everyone, it seems, even a giraffe, is looking to him to DO SOMETHING. At least, that’s how it registers with me – and him!

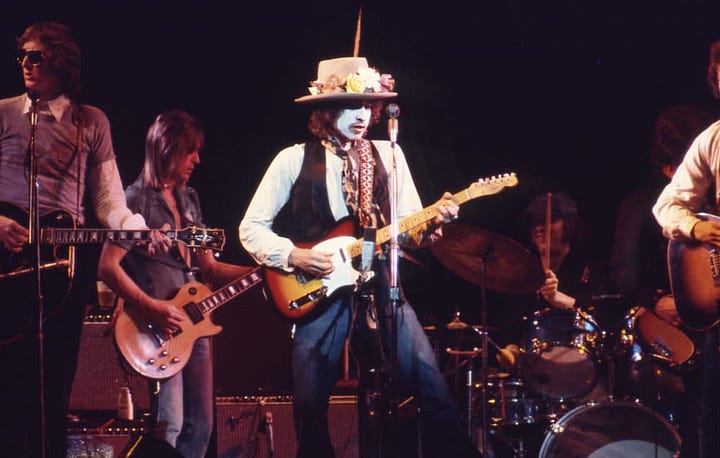

We cut to the town’s pavilion, where there seems to be a funeral going on for sweet Mrs. Henry, her wide-eyed, life-like corpse staring out of an open-faced casket. Everyone looks all upset, a black man with half of his face in stars and stripes (maybe it was actually 3/5) is there, too and we find a white-faced Jim James, all white-faced Rolling Thunder-esque, from My Morning Jacket singing a beautifully mournful version of one of the Basement Tapes songs that almost got away, “Goin’ To Acapulco.” It’s an aching tune about a guy sadly leaving to go have fun at some distant brothel. Townspeople stare back at Haynes’ camera, as if looking for someone, anyone to help. How can this be happening? (We know that feeling in 2020.)

Then on the stage, an ancient, Old Testament-bearded, wheelchair-bound Pat Garrett (who caught and killed Billy The Kid a newspaper tells us) has sold out the town of Riddle. Billy, wearing a Rolling Thunder Review-style plastic mask, decides to speak up on behalf of the town he just walked into. Nobody asked him but they didn’t have to. His conscience told him IT WAS THE RIGHT THING TO DO.

“Do you think you’re speaking for the people, sir?” a belligerent man asks. “We know how to handle people like you.” Billy gets thrown in jail (think recording “Self-Portrait”), somehow a nameless friend gets him out and tells him, “Your secret is safe with me.”

As the film winds down, Billy escapes by riding the rails like a hobo or Woody Guthrie and, lo and behold, finds a dusty old guitar on the train. Our last shot of him is sitting in the open boxcar, guitar in hand, riding towards another town, another crisis, never stopping, a never-ending tour.

Now it seems ridiculous to consider that the particular time period represented in the film as the early 70’s (when Dylan was about as removed from the “scene” as he could be, holed up in Woodstock drying out, reconfiguring, reconsidering, reconnoitering) should suddenly make you think of how he had to be involved, had to keep writing and recording and performing. How it seemed to him in that retirement, that a withdrawal was just not in the cards, not now, not ever, just not possible, not something he could ever do and live with himself. Something “in the moonlight still hounds him” as he put it on the underrated “Handy Dandy” on the equally underrated “Under A Red Sky.” Even as the curtain comes down on a 79-year-old.

Sure enough, the delightful and wholly unexpected new album “Rough And Rowdy Ways” is generous, unflinching, rambunctious, thoughtful, fun. When you’re handed a Nobel Prize for Literature and you’re so rattled you can’t even speak or say thanks for the longest time – at least that’s how it looked to me – what card can you play that’s going to top or even match that?

Was that why he retreated into cover albums of songs nobody wanted to hear him sing? What brought forth this album? Was it the pandemic halting his Never-Ending Tour (Wasn’t he supposed to be overseas in Japan?) that gave him some unplanned, unscheduled time off. Did he think, aw, what the heck, instead of welding a new gate or sketching some empty road…let’s do another record? We will likely never know the answer to that.

Looking back, wasn’t that the case in 1997, when he was unexpectedly snowbound on his Minnesota farm and somehow found the time and the inspiration for the giant comeback album “Time Out Of Mind,’ a record that earned him three Grammy Awards including 1998’s Album of the Year? Or at least, that was the story we heard.

Did the temporary halting of the Never-Ending Tour give the old master some unexpected free time? Was he chiseling away these songs all along and just waiting for the right time to record and release them? Or, most daringly, did his artist’s antennae tell him, nudge him, poke him, plead with him to speak up NOW? That we needed and wanted to hear from him. Hence “Murder Most Foul.”

One of the daunting challenges for anyone trying to evaluate an artist’s career is, looking back, a writer can never recapture “the moment” when something happened. When future writers look at, for example, “Murder Most Foul,” they may well wonder what spurred a nearly 80-year-old, creatively silent for eight years, to drop this song in this place and in this time? Those of us who were here to catch this familiar croak coming off our computer screens or out of our car radio speakers won’t forget how it hit. Just as, in 1885 when the most popular writer in the world, Mark Twain, released a novel with a runaway slave as its unspoken hero and hardly anybody (judging from reviews at the time) realized what a revolutionary novel it truly was.

Nobody, even Dylan, could have expected this kind of reception. To achieve his first No. 1 song, a 17-minute job at that, an absolutely glorious reception from record critics, the finest album reviews of his remarkably long career. Who could have believed that the Bob Dylan who was absolutely torching the candle at either end in 1965 (Haynes demonstrates this perfectly in with a great imaginative shot of a mannekin-like Dylan soaring up into the sky in “I’m Not There.”) Who would have thought he had another 55 years to live and another 32 albums to release – not to mention thousands of concerts and who knows how many bootlegs?

The wealth of Dylan material compiled over these many years is staggering. The books, the essays, the magazine articles, the interviews; there’s just so much. For a not particularly cooperative or eager interview subject, there are at least three good-sized compilations of Dylan interviews. Where the hell do you begin? That’s where “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography, Edition Three” comes in.

The third edition of “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography 1961-2022” is available on Amazon and locally at Barnes & Noble and Midtown Reader.

Outstanding work! 👏 I’m definitely buying your book and it’s going on my Dylan shelf.