EDITOR’S NOTE: Baseball honored Jackie Robinson the other day, every player on every team wearing his number 42. Robinson’s sad finale was included in my baseball book “Last Time Out” and I thought it appropriate to share that chapter with my readers to honor the late great Dodger. “Last Time Out” is a collection of stories about the final games of 43 of baseball’s all-time greats and the first MLB game played by my son, John. Here’s a look back at Robinson’s sad farewell.

When he stepped out of the Ebbets Field dugout, the stadium was emptying and it seemed like he could hear most of the city crying. Broken-hearted Dodger fans were again cursing their World Series luck, heading home sadly to a lousy dinner and another lousy offseason.

As it turned out, Brooklyn’s very last World Series game in cozy Ebbets Field was just about to come to a close. Jackie Robinson, due up third, couldn’t have known what lay ahead for him or his franchise. Not just the last at-bat of the World Series and the last at-bat of the 1956 season. It would also be his final at-bat in the big leagues. The journey that had begun with so much drama so long ago was finally about to end. What a rotten ending.

To think that the night before, early Tuesday evening, his dramatic 10th-inning hit against the New York Yankees— repaying them for an earlier insult—had forced a Game 7 here in Brooklyn, lifting the hearts of Dodger Nation. That title last year wasn’t a fluke; they were going to win it again. After all those losses to the Yankees, Brooklyn was going to start a dynasty of its own. There was going to be one more game for the baseball championship.

Yeah, Dem Bums were coming back, starting 27-game winner Don Newcombe in ol’ Ebbets Field against whomever the Bronx Bombers would trot out. Didn’t matter.

Brooklyn was going to do it again and send that stuck-up, pinstriped mob back across town to stew on a Game 7 loss all winter.

Except it didn’t quite work that way. Not at all. Robinson knelt down in the on-deck circle and could hear how quiet the park was. Ebbets Field wasn’t usually like that. Even in a loss. The hurt was palpable. And constant, it seemed, when the Yankees were involved.

After the Dodgers had jumped out to a 2–0 Series lead, sparking hopes of a World Championship repeat, the Yanks won the next two games. Then in Game 5, New York’s Don Larsen had thrown a perfect game, completely silencing the already near-dead Dodger bats and moving the Yankees within a victory of the title.

But in Game 6, the Dodgers fought back with one of the most stirring triumphs in franchise history to set the stage for this dramatic Game 7. On Tuesday, Dodgers manager Walt Alston had sent reliever Clem Labine to the mound to face New York fireballer Bob Turley, and the two of them put on a pitching display to nearly rival Larsen’s brilliance. Labine hadn’t started a game since the second game of the 1951 playoffs vs. the Giants, and Turley was razor sharp. And neither team was hitting.

Through nine pressure-packed scoreless innings, the tension rose over Ebbets Field like a magnetic field. In the bottom of the eighth, Labine himself clouted a double, the only extra-base hit of the day for the weak-hitting Dodgers. After two outs, Yankees manager Casey Stengel ordered Duke Snider walked to put it all on Jackie Robinson’s shoulders, to see if the proudest Dodger could force a Game 7 with a clutch hit.

The Brooklyn fans were aghast. True, it hadn’t been that great a season at the plate for Robinson—he hit only .275 and in the World Series, he was just 6-for-24 (.250). But walking someone to face Jackie Robinson?

This time, the Yankee fireballer won the battle, getting Robinson to pop out, preserving the scoreless tie. The situation repeated itself in the 10th inning with the game still score less. Again, Stengel ordered Snider walked to face Robinson once again with the game on the line.

Triumphantly, Robinson came through, lashing a rocket over the head of Yankees left fielder Enos Slaughter—his final big-league hit—and Junior Gilliam came all the way around to give the Dodgers a 1–0 10-inning thriller and set up a Game 7 back in Brooklyn with their 27-game winner on the hill. After a victory like that, how could the Dodgers not win?

With Game Seven winding down, Robinson quietly shook his head. He looked up at the scoreboard and saw all zeroes on the Brooklyn side. The Yankees had a run for every inning, leading 9–0. It all seemed a cruel joke. He took one last long look around the ballpark, the signs along the left field wall, “Brass Rail,” and “Luckies Taste Better,” and “Stadlers,” and, of course, the “Van Heusen Shirts” sign out in right-center field. He could see the two-tiered stands, the World Series banners ruffling emptily in the cool October breeze, all nearly deserted now.

There had been so much optimism in the place just a couple hours ago. Where did it all go wrong? In his very first big-league season—1947—Jackie Robinson had led the Dodgers into the World Series, and they lost to New York in seven games. Here he was, leaving the same way. Well, almost the same. In that 1947 World Series, the Yankees broke it open at the finish of that Game 7 to take a 5–2 win and take the title. At least, it was close for a while. Wednesday’s box score wouldn’t be as kind.

At first, it looked so good for the Dodgers. They were going to start 27-game winner Don Newcombe, while New York manager Casey Stengel decided to bypass veteran ace Whitey Ford to go with skinny right-hander Johnny Kucks, an 18-game winner during the regular season. Kucks wasn’t bad, but he hadn’t been able to win a game in over a month.

Though Newcombe bore the tag of a man who couldn’t win the big one, surely he’d shake that 0-3 World Series mark here. This was a different Dodger team, wasn’t it? Maybe not. There were other off-the-field indications that Newcombe might not have been the Dodgers’ best choice. When he had been shelled earlier in the Series, he was so upset about it that he got into a brawl with a parking lot attendant on the way home.

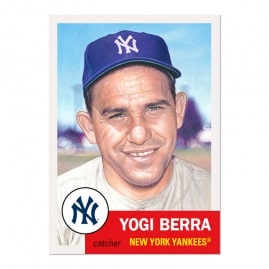

His final World Series start wasn’t much better. Hank Bauer opened the game with a single and stole second. Newcombe fanned Billy Martin and then Mickey Mantle. He got an 0-2 count on Yogi Berra, just one strike away from getting out of the inning unscathed. But his third pitch to the little catcher was one he’d always regret. He fired a high fastball, a fat one, and Berra lined it over the right field fence. 2–0, New York.

In the third, Berra did it to him again, ripping another two-run homer to make it 4–0, Yankees. The Brooklyn fans were crestfallen. When Elston Howard blasted a Newcombe pitch into the seats in the fourth to make it 5–0, Alston had seen enough and gave him the hook. So, from the sound of it, had Brooklyn’s faithless. As Newcombe slowly walked off the mound, the Dodger fans cut loose with such a chorus of boos, even the Yankees were appalled.

“I feel great that we won,” Whitey Ford said afterwards, “but it was awful the way the fans booed him. Why should they boo a guy who did so much for them this year?” Newcombe was a good symbol for the Dodgers on this day, Robinson could see that. He was one of the best pitchers in baseball, everybody knew that. And the Dodgers were one of baseball’s best teams. But they weren’t quite as good as the Yankees. And never would be.

This final time the Yankees would triumph in a World Series over the Dodgers during Robinson’s career—this 1956 title—assured that. Writing for the New York Herald Tribune, the famed columnist Red Smith began his column with the departure of Newcombe, too. “This is a game for boys, and Don Newcombe is no kid,” Smith wrote. “He is large and grumpy and not necessarily the most cuddly character in baseball. He is mean to hitters and a soft touch for gossips who have made him the victim of a cruel slander. Because the Dodgers’ big pitcher can win 27 games in the National League but has never won one in a World Series, they call him a coward, a choke-up guy. “It isn’t true, but now he may never have a chance to prove it false. . . . They booed Newcombe out of the park.” “‘Calling all parking lot attendants,’ the funnymen in the press box were shouting as the big guy shambled off. ‘All parking lot attendants—take cover!’ It wasn’t exactly hilarious.”

Robinson could feel that anger, that sense of betrayal, kneeling in the on deck circle, looking at Kucks. Thanks to that 9–0 score, the same as a forfeit, Robinson wondered how many sarcastic sportswriters would note it in their dispatches the next day. Many did.

Robinson thought about the other times he’d faced the Yankees in the World Series. Five different times in a 10-year career. He lost in five games in 1941 and 1949 and lost in seven in 1947 and 1952. Now this. A Game 7 loss in 1956. Damn. He looked up to see Snider rifle a shot back through the box, only the Dodgers’ third hit off Kucks. It was now up to him.

He dug in, looked out at the right-hander, saw Berra behind him, Newcombe’s tormentor, and tried to focus. It went by too quickly. Suddenly he had two strikes on him and Kucks’s pitch was on its way, sinking and twisting. Robinson swung and missed. The ball hit the dirt, Berra trapped it and Robinson had to run. He got a couple steps off, saw Berra’s throw snap into Bill Skowron’s mitt, and stopped. It was over. All over. The Yankees were world champs again.

Brooklyn’s reign as world champs lasted but a year. A fluky year. Robinson’s heart ached as he watched the Yankees celebrate again. On his field. A little over two months later—64 days to be exact—the Dodgers, figuring it was time to break up their aging club, dealt Robinson—with no warning or previous discussion—to the New York Giants for Dick Littlefield and $30,000. Everyone, including Jackie, was shocked by the move. “It is impossible to think of Robinson except as a Dodger,” wrote Red Smith in the Herald-Tribune. “Other players move from team to team and can change uniform as casually as the Madison Avenue space cadet sheds his week day flannels for his weekend Bermuda. His arrival in Brooklyn was a turning point in the history and the character of the game; it may not be stretching things to say it was a turn ing point in the history of this country.”

One month later, Robinson had decided to retire. Instead of sharing the news with the New York press, he cashed in his chips and sold his exclusive story to Look magazine, stiffing the voracious newspapermen who, through out his career, had built him into a folk hero. Smith, naturally, was one of the first to let off steam.

“The fact that he gave [the Dodgers] full value on the field and the fact that after 11 years, they sold his contract without consulting him, these do not alter the fact that everything he has he owes to the club,” he wrote. “If it is true that Jackie Robinson has, for a price, deliberately crossed his friends and employers past and present, then it requires an eloquent advocate, indeed to make a convincing defense for him. From here, no defense at all is discernible.”

That was nothing. The next year, the team left Brooklyn forever. The strikeout by the way, was somewhat unusual for Robinson, a player who fanned just 291 times in 4,877 big-league at-bats. It was a heck of a way to end a World Series, a season, a career. It was also, some fans noted later, Kucks’ only strikeout of the game.

If you’re interested, “Last Time Out” is available locally at Books A Million and Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

John. Always great work. Enjoyed this unique perspective of the final at bat of Jackie Robinson!