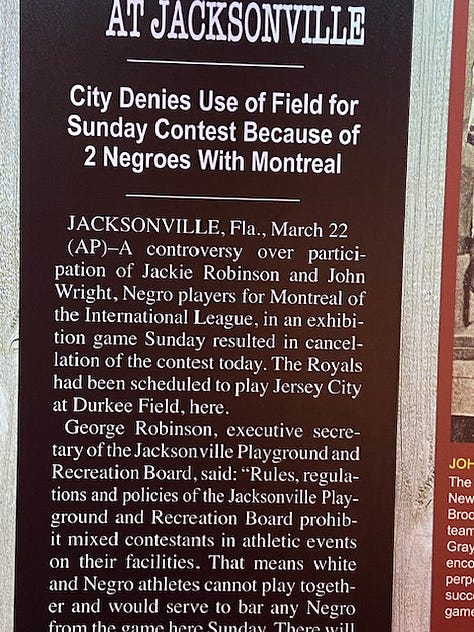

And I quote: “Strangle holds, razors, horsewhips and other violent implements of argument will be barred at the baseball game at Island Park this afternoon when the baseball club of Wichita Klan Number 6 goes up against the Wichita Monrovians, Wichita’s crack colored team…The umpires have been instructed to rule any player out of the game who tries to bat with a cross.”

This is from an article posted on the wall at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum on 18th and Vine in Kansas City, Missouri that bore the headline: “Only Baseball Is On Tap At Island Park, Klan and Colored Team to Mix On The Diamond Today”

It is one of all sorts of old-time articles from back in the day posted on the museum walls, the Klan facing a “colored” baseball team in Kansas. Oh.

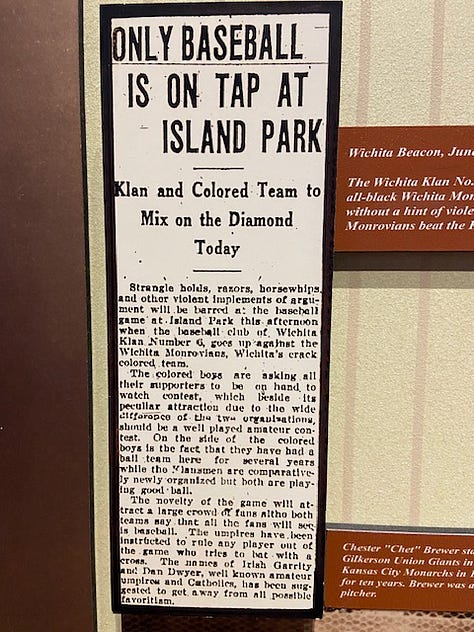

If you have never been to the Negro Leagues museum in Kansas City — my second trip — you leave with an unsettled feeling in your stomach or maybe your heart. We all know about Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey and what Robinson faced in 1947, breaking into the major leagues as the first black player. We’ve also noted MLB’s more than somewhat belated attempt to include Negro League statistics alongside “traditional” MLB statistics — a mistake, in my view.

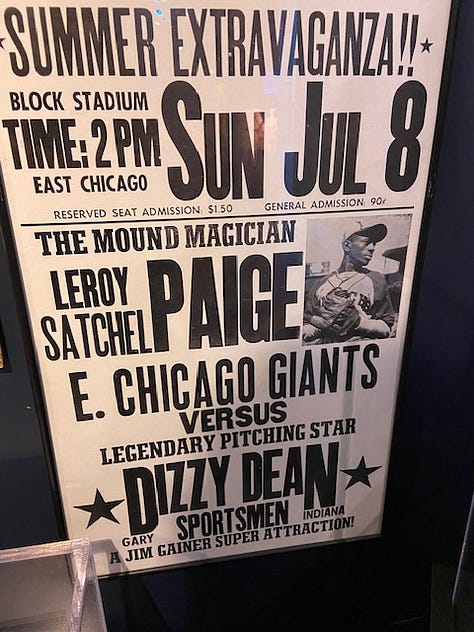

What we haven’t — and can’t really ever know — is what it felt like to be a terrific player in the game of baseball, perhaps as good in your game as a Babe Ruth or a Joe DiMaggio or a Walter Johnson was in their game but denied the chance to compete with them on the same field, except, perhaps for barnstorming games like the one advertised — Satchel Paige vs. Dizzy Dean, games that went on neither man’s career record, played on a wide-ranging assortment of fields with amateur umpires, lineups of farmers, mechanics, salesmen mixed in with a few major leaguers.

They were exhibitions, of course. How hard Dizzy Dean or any big-time major-leaguer like Bob Feller tried in any of these games is impossible to know. And while it is probably the right thing to do to try to make amends for these slights by inducting a bunch of Negro League players belatedly into the Hall of Fame long after their death — last time I visited, I was surprised at some names I did not recognize — do we really know how they would have done vs. major-league competition day after day after day? We don’t. And won’t.

Of course, now we all agree it was wrong and certainly, there had to be some players then who knew that, who’d played against some of these Negro League stars and knew how good some of them were. And you had to think that if a few of those white major-league stars, maybe 10 or 15 of the very best players in the game stood up, possibly went to the newspapers and said that these Negro League players needed to be given a chance, things might have changed.

Yet I’ve never read of a single player who ever mentioned the idea of a strike, a boycott of MLB games until Negro League players were permitted. You wonder if that idea had occurred to any of them. Even players with exemplary character, like a Stan Musial or a Robin Roberts.

But then again, had they done that, some of their friends, those marginal white players would have lost jobs, friendships, careers. And society in general would have almost certainly rejected that concept and might well have taken their protests out in lack of attendance. That might have been the owners’ fear. The Civil Rights Act didn’t happen until when?

In A.J. Liebling’s “A Neutral Corner,” a posthumous collection of his extraordinary New Yorker stories on boxing, he quotes from a prominent Louisiana newspaper (The Shreveport Times) in the 1950’s that carried an editorial claiming “four eminent scientists” suggested “the Negro IQ becomes progressively lower as he ages.” Liebling cited this article to make his case for the venerable boxer Archie Moore getting smarter as he aged, but that a newspaper would run an editorial like that, not to mention “The Klan vs. the Colored Team” shows you, sadly, where a good part of America was then. And we hope “then” is still an accurate term.

Seeing the artifacts of these Negro League careers, the gloves and bats and traveling trunks, even the write-ups from black newspaper writers at the time, you wonder why some Senator or House of Representative member or even a President didn’t think about doing or saying something? Wasn’t baseball our National Pastime?

What do you learn? Well, I guess it was fun to note that Yankee Elston Howard was credited with inventing the metal “donut” weight to put on the end of the bat for warmup swings. And it was great to see the expansive display of materials for former Carrabelle resident Buck O’Neil, who was finally inducted into the Hall of Fame after he had passed. Having had a chance to chat with Buck over the phone just before the Ken Burns’ Baseball series came out on PBS, there could not have been an ambassador for the game with a sunnier disposition, an old soul with the unflappable dignity of one who’d seen and been through plenty and still remained optimistic, hopeful, unfailingly generous. And forgiving.

In reviewing my online friend Paul White’s book “Cooperstown’s Back Door” a while back, he was deeply disturbed about the Hall of Fame’s general treatment of former Negro League stars and their uncertain actions in recognizing these players. I nod to White’s scholarship and passion but it is — and remains — a foggy area to me.

That baseball went ahead and decided to include Negro League records into the long-established MLB record book seemed a way-too-late move towards political — if not statistical — correctness. No, I don’t believe for a minute that former Homestead Grays’ star catcher Josh Gibson had a lifetime .372 mark, nor do I believe that something like 10 of the top 15 longest home runs in history were hit by Negro League stars. Satchel Paige claimed he threw 50 no-hitters. An extensive look at the actual record shows four.

So, I wish I could say visiting the Negro League Baseball Museum was an uplifting experience. It wasn’t for me. The museum is well done, interesting — if unsettling — and it’s a visit that stays with you if you’ve spent a good part of your life watching, reading, playing baseball. And maybe it should.

It was also interesting to note that in my hour plus there on a Friday morning, I didn’t see a single black face. Other than those on the walls. They’ve moved past it. We’ve moved past it. Or have we?

I toured the museum last month and had many of the same feelings. In my opinion, MLB is in a no-win situation with the inclusion/exclusion of Negro League stats. On one hand, it belatedly corrects a historic wrong that was for too many years ignored as players were legally, culturally, socially, and professionally spat upon. On the other, as you note, verifying the stats is challenging at best and in many eyes an overcorrection of history.

I lean toward including them, because I tend to fall on the side of inclusion in all cases. The problem in this country is that society remains largely separate and dramatically unequal, and those in power want to keep it that way.

Thank you for an excellent piece.

We should have moved past it, but nobody can deny that it happened. Should people tour the museum? Sure. There is only so much history that we can erase.