It’s funny how sometimes my somewhat warped writer brain steers me somewhere I never would have expected to go. Do I follow it? Or move on?

Yesterday afternoon, I was reading through “Good Vibrations: My Life As A Beach Boy” by Mike Love, one of the group’s lead singers who also had the good fortune to be a cousin of principal songwriter and visionary Brian Wilson. After reading all about the court cases and legal squabbles that ruined the late-in-life attempts at reconciliation and reunion with all the members of the band, I was nauseated.

Reading all about that fighting about money, thinking of Brian Wilson now suffering from dementia, why, all this crap couldn’t have been further from the spirit of the joyous, uplifting, celebratory songs of The Beach Boys. When you think of “The Beach Boys” you don’t want to be thinking about lawsuits and court cases.

It reminded me of The Band, who went through the same sort of thing. The five of them came on the scene mysteriously with the air of brotherhood, four Canadians and a guy from Arkansas, who all sublimated their individual egos and considerable talents for the sake of great, communal, all-for-one, one-for-all music.

It was only later on, when songwriter and visionary Robbie Robertson got the songwriting credit — and the money — that the others started bitching about their share and credit. And that whole communal thing went down the drain.

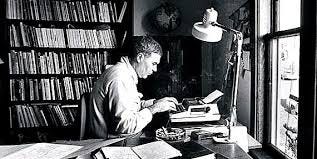

Why this directed my strangely associative brain to the case of the late great short story Raymond Carver, I’m not certain. Only that I had remembered reading some long, harrowingly detailed stories of the brutal in-fighting between Carver and his editor, Gordon Lish. After the fact, of course.

Carver became known — and acclaimed as a worthy successor to the Ernest Hemingway tradition of minimalist short story writing but late in his career — he was to die of cancer in 1988 at 50 — Carver started to reject, question, revolt against Lish’s heavy editing hand.

The two of them had worked so well previously, Lish’s editing, Carver’s writing was celebrated in literary circles. Critics offered high praise for Carver’s work and the editor took a bow, too. Except now, after the acclaim, now the writer, well, he wanted the editor to put the pen down and this time, let the writer’s words stand as written.

This raised an unusual, maybe even an ethical question. How much does/should an editor impact a writer’s work? It’s a good question and one that isn’t easily or simply answered. The words, of course, are generated by the writer. It’s up to the editor to try to present to the reading public in their finest possible form. But what if writer and editor disagree?

In the newspaper business, the answer was, in just about every case, the editor would have the last word. Even if it was, in the long view, wrong or short-sighted. I previously told the story about the busy-body editor insisting that I had misspelled the name of the winner of fishing tournament (I hadn’t) but he became so obsessed with that, the headline he wrote over the story was completely incorrect! And who looks like the idiot?

With fiction, the editing process is much more subtle and, we would guess, more subjective. Can you imagine a John Updike NOT getting a story in the New Yorker? Yet look at this rejection letter from editor Roger Angell shipped to the noted short story writer Ann Beattie, author of “Dinner At The Homesick Restaurant.”

“Dear Ann: I’m sorry — extremely sorry — to say that we’re sending back “Another Day.” No one here could recognize these people; they don’t seem to have any connection with real life. The story is written with wonderful clarity and intensity, but the gigantic egos and destructive behavior of your characters are presented so bluntly and cold that they blot out everything else…”

So, after all their success and acclaim, when Carver sat down and wrote this to Lish, you can imagine the editor wasn’t particularly receptive.

"Dearest Gordon, I've got to pull out of this one. Please hear me… I've looked at it from every side, I've compared both versions of the manuscripts… until my eyes are nearly to fall out of my head.""

What had happened was Lish’s edited version of these recent stories Carver wrote so little resembled what Carver had originally sent him, the writer was uncomfortable. Who was writing this, anyway?

According to Gaby Wood’s story in “The Guardian”, “There were three stories in particular that were so cut back that he felt he could not live with them, whether or not they were objectively better: "Even though they may be closer to works of art than the original," he wrote to Lish, "they're still apt to cause my demise."

“The letter is an incredible document,” Wood writes. “a missive from a man both indebted and imperiled, unsteady, spewing. It's at once a plea and a manifesto – it reveals the extent to which writing was connected to Carver's sense of self, and it reads much more like the characters he originally wrote, who, far from leaving things unspoken, say too much and still manage to scutter around the main point, which is perhaps only anxiety itself.”

So, 20 years after Carver’s death, his widow, Tess Gallagher, who had seen the stories in their original form, decided to bring them out the way he initially wrote them. Which prompted Wood’s story in The Guardian. And re-thinking the Lish-Carver relationship.

“She describes the process as a "restoration",”Wood wrote. “and says it has taken 12 years for Carver's words to be exhumed from under Lish's hand, so extensive were his marks. It makes the stories sound like the literary equivalent of the Sistine Chapel.”

We are used to musicians re-packaging their outtakes. Both The Beach Boys and The Band have done plenty of that as has just about every other famous musician you can think of. Bob Dylan has an entire Bootleg Series made up of outtakes. But we haven’t really had that happen with writers. Not yet.

I haven’t read the re-worked stories but did teach three Carver stories in my days in the classroom. I taught “Neighbors,” “Errand” — his final story, about the death of Anton Chekhov, and his most famous story, “Cathedral.”

I could definitely see the Hemingway influence in his writing and his deceptively simple style. He wasn’t somebody who had my students reaching for the thesaurus or puzzled over his sentence structure. It was clean, dialogue was clear and sharp.

My students got a kick out of “Neighbors” and enjoyed Carver’s clear-eyed grasp of human nature and our latent curiosity. It’s a fun and frisky read, one that now I wonder how much Lish fiddled with.

I’ve served my time an editor and my goal, always, was to stay the hell out of the way and help the writer have his/her say. You know that ol’ do-unto-others thing. Not everyone agrees with that approach.

Raymond Carver did agree that with Lish as his editor, he likely rose higher in literary circles than he might have with someone else. As he wrote to Lish in that same letter: "You've given me some degree of immortality already."

But where did the writer end and the editor begin? Something to think about, isn’t it?

HERE ARE LINKS TO “NEIGHBORS” and “CATHEDRAL”

(Cut and paste in your browser)

https://tnsatlanta.org/wp-content/uploads/Neighbors-Carver.pdf

https://thelondonmagazine.org/cathedral-by-raymond-carver/