"Take it easy, Garth"

Remembering The Band's Garth Hudson

EDITOR’S NOTE: It would be wrong to overlook, ignore, forget about the passing of Garth Hudson yesterday, the last remaining member of The Band, one of the most influential and important of all rock groups. Hudson was possibly the finest all-around musician ever exposed to a rock and roll audience but I’m not sure he ever got his due. Hiding behind that bush-like beard, never speaking on stage, he let his playing do the talking for him.

Forgive me if this is too radical a thought, but without Garth Hudson, rock history, as we know it, might have been completely changed.

Not only did the amazingly talented Hudson find endless ways to weave impeccable, often irresistible musical pathways to lift, support, color, carry Robbie Robertson’s story songs with brilliance, subtlety and imagination — a career achievement to be sure — he did something else that may have had a major impact on rock and roll history.

Certainly, his role in The Band was a pivotal one, providing the diverse, always supportive musical base for each of their three singers, bassist Rick Danko, pianist and occasional drummer Richard Manuel and regular drummer Levon Helm, and he seemed to be able to connect with principal songwriter and guitarist Robertson in a seamless, almost intuitive way.

But except for his in-concert showcase “The Genetic Method” a number added for him to show off and give the rest of the group a breather, you never thought, “Oh, it’s time for Garth’s solo” like you often do with other keyboarders in other bands. He always made it a point to fit in, to make the whole sound picture complete, full, satisfying.

With Garth Hudson, there was even more. For he recorded — and you’d also have to say engineered, brilliantly, too — Bob Dylan’s historic Basement Tapes in Big Pink (mostly) during that famous lost summer after Dylan’s motorcycle accident. Attempting to record and balance the noise from voices, two guitars, an organ or piano, a bass and drums in the smallish basement of a ranch wedged in the Saugerties of upstate New York had to be a daunting task. But his recordings, most of them, anyway survive.

While time and perspective has established their importance in the career of Dylan and The Band, too, for that matter, that wasn’t always the case. For a long time, nobody knew a thing about them.

There was Dylan’s motorcycle crash on July 29, 1966, just 63 days after his exhausting and controversial world tour had ended at the exact spot his 2024 tour ended, London’s Royal Albert Hall.

We’re not exactly sure when Bob was well enough to start playing with The Band, minus Levon, but they began at Bob’s house, “The Red Room” then relocated to the Big Pink house on Stoll Road and set up in the now famous basement, now a tourist site. (Yes, I had to drive to the house, too!)

Though manager Albert Grossman reportedly told them to get a place in Woodstock, “where they could make as much noise as they wanted,” The Basement Tapes aren’t like that. There aren’t raucous guitar solos or pounding drums or the excess you might expect from a rock band finally free to make as much noise as they felt like. Instead, they sat in a circle so they could see — and hear — one another with their famous visitor pounding out songs on an upstairs typewriter or making them up at the microphone every afternoon. And they created a set of songs unlike any others anybody ever heard; bawdy, funny, somber, playful, tunes that weren’t exactly Hit Parade material but were, on the whole, just delightful, a side of Bob Dylan we’d never see again.

In the process of Dylan re-discovering his muse, The Band pitched in with such enthusiasm, their eyes and ears wide open, they found their own sound, their own musical vocabulary. With Garth Hudson recording it all, or just about all of it when Bob would occasionally tell him, “Garth, you’re just wasting tape.”

Having spent a summer in those unofficial musical “classes” — Robbie noted there often seemed to be a method behind what material Bob brought them — it wasn’t surprising that when “Music From Big Pink” came out, The Band seemed fully formed. It was a debut album, sure, but it didn’t sound like a bunch of kids trying to make some noise and get somebody to notice them. They were past that.

The Band seemed to have a collective, all-for-one, one-for-all vision, a unity and an anonymity that was certainly the opposite of Dylan. There was an air of mystery about the whole thing that was both immensely appealing and unusual at the time.

Meanwhile, the career, the myth, the legend of Bob Dylan, officially musically silent since the release of “Blonde On Blonde” in June of 1966, somehow grew. Was he seriously hurt in that motorcycle accident. Was he maimed? Done? Had we heard all we were going to get from him?

Columbia Records, not used to this long a period of silence from Dylan — remember, he’d released three albums, one a double-disc, from March of 1965 to June of 1966 in a 15-month firestorm of activity — hurriedly released “Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits” in late March of 1967, wondering if that was it from their star.

While Dylan did release the modest “John Wesley Harding” just after Christmas in 1967, Dylan fans wondered if their man had truly been totally silent since going over the handlebars of that Triumph. And what was this soft acoustic stuff all about?

Amazingly, interest in Dylan through those 17-months seemed to intensify. It might have been about the only time in recording history where an artist’s silence actually advanced his career. Dylan’s management was admittedly surprised by it all. These fans wanted MORE.

In June of 1968, Rolling Stone Magazine’s Jann Wenner leaked out word of a Dylan Basement Tape, Hudson’s summer recording project. Bootlegs appeared and finally, in 1975, Columbia Records officially released a double album set of Dylan and The Band cuts. Bob’s take was “I thought everybody already had ‘em.”

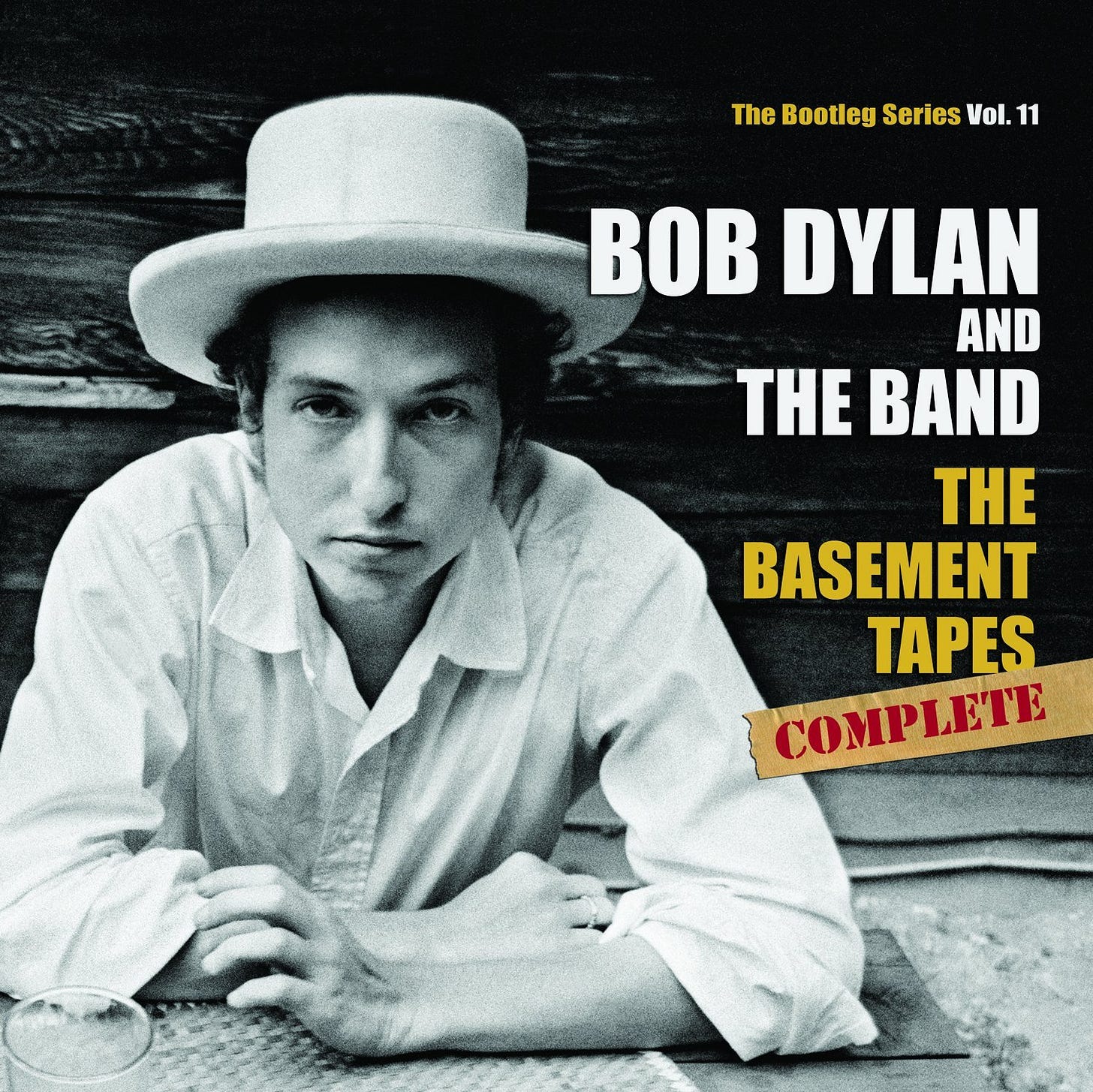

But the reviews, the acknowledgements of what Hudson had worked so hard to capture that magical summer in the Big Pink basement completed the picture of both Dylan and The Band and helped explain their kinship and debt to one another. A more complete version, “The Basement Tapes Complete,” a six-disc set, came out in 2014 to great response. And had Hudson not commanded the reel-to-reel, we might never have heard any of it.

In “The Last Waltz,” their gloriously filmed farewell by Martin Scorsese, Garth Hudson barely speaks, probably like in real life. Supposedly, there’s quite a hilarious and a considerably stoned recitation by Hudson on one of the Basement Tapes’ sessions but the editors have spared us that cut, unfortunately. The music will have to do it.

To me, one of the great inside jokes of “The Last Waltz” is when the band opens the show with Ronnie Hawkins, the guy they started with. Hawkins rips through a delightfully brassy “Who Do You Love?” and near the end quips, “Take it easy, Garth, don’t you give me no lip.”

As far as we know, Garth Hudson didn’t give anybody much lip. But he had plenty to say.

John Nogowski is the author of “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography, 1961-2022, 3rd edition.” Currently available on Amazon.

I’m very thankful that you let me know about this story! During the time of the basement tapes, I, sadly, wasn’t following Bob. My loss, because so much happened. This is really a great story, and although I had previously read about some of this, you included many more details. I always appreciate your stories! I also now know more about Garth … and sadly, now he is gone. I believe that his memory will always be a blessing. Thank you, John!

In 2014, my girlfriend gifted me the six disc Basement Tapes for Christmas. She’s a keeper!