Telling history to go to hell

Fury tries to regain title on Saturday in Saudi Arabia

EDITOR’S NOTE: If you’re a boxing fan, there’s a terrific show “Fight Life” on ESPNews or Channel 207 on Direct TV at 7:30 tonight. It’s a good preview for Saturday’s title fight.

On Saturday in the sands of Saudi Arabia, the new “hot spot” for heavyweight boxing, former heavyweight champion Tyson Fury, all 6-foot-9 of him, will try to regain the heavyweight title he lost to Ukraine’s Oleksandr Usyk, a 37-year-old who came in with only 21 professional fights, via a split-decision in May.

Heavyweight history is shaking its collective head. Good luck, Tyson. Regaining the title you lost? Right. Hey, can you tell history to go to hell?

For the longest time, regaining what you lost seemed an impossibility. You’re the heavyweight champion of the world, you try to defend your hard-won title, have a bad night, get caught with a lucky punch, lose a close decision and all of a sudden, goodbye, title.

“It’s OK,” you think. “I’ll get it back in the rematch.” Except you don’t. Nobody could.

Ex-champion after ex-champion after ex-champion tried and failed. It was a curious thing. All of these fighters — James J Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, James J Jeffries, Jack Dempsey, Max Schmeling, Joe Louis, Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott all attempted to regain the title after losing it. Every one of them failed.

You had to wonder if it was a psychological barrier. A psychic wall that the once-champion of the whole wide world was unable to scale, once a man had beaten him. It didn’t seem as if it was a physical thing; a fighter can’t lose that much in a year or two, can he? Will that be what Tyson Fury is staring down across the ring as well as Oleksandr Usyk?

Whatever happens on Saturday, Fury has been one of the most unusual of heavyweight champions. Breaking into Don McLean’s “American Pie” in mid-ring after winning the title, well, that’s not the kind of thing you’d expect, is it? The Gypsy King nonsense, seating himself on a throne, his trilogy of fights with Deontay Wilder were wild, thrilling, the kind of heavyweight combats that go down in history.

The fight with the stubborn Usyk in May was puzzling. Usyk, a natural light heavyweight, was moving up in weight. A southpaw who’d only had 22 professional fights by age 37, it would seem that Fury’s experience, his size and power would overwhelm the challenger.

But it didn’t. Fury spent more time than he should have posing, farting around in the ring and didn’t really land the kind of bombs on Usyk that he had on others, Wilder, for instance. Fighting southpaws, that is, fighters who lead with their right hand instead of the traditional left, can be tricky and Usyk, though without a lot of pro fights, is quite ring-wise, shifty and he takes a great punch.

Fury was rocked and took a standing eight count in Round 9 which was probably the one round that decided a very close fight. It'’ll be interesting to see if Fury can really assert himself from the early rounds like he did the first time and take him out of there.

If Usyk survives an early assault, Fury might have a difficult time outpointing him. He’s that clever. And he finished strong the last time.

What we don’t know is what Fury has left; does he still have that “fury” that a fighter really needs? As we’ve seen with recent examples like Evander Holyfield, Wladmir Klitschko, Roy Jones, there can come that one night when a fighter gets into the ring one time too many and suddenly discovers that while he might look in shape and ready to go, once the fight commences, everything is gone, combination punches, power, etc. It’s like someone unplugged that part of the brain that lets them fight. It’s odd, disturbing and unsettling. It’s like the message from the brain just doesn’t get through to the limbs. Will we see that Saturday night?

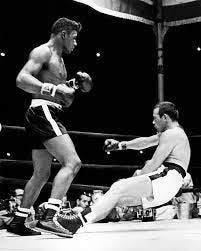

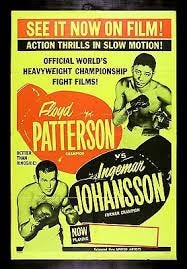

The first heavyweight to break that string of ex-champion failures was Floyd Patterson, who was also the youngest heavyweight champ at the time, defeating an ancient Archie Moore for the title left vacant by Rocky Marciano’s retirement. But Patterson promptly then lost the crown to Sweden’s Ingemar Johansson in 1959 when Johansson’s right hand put the glass-chinned Patterson on the canvas seven times in three rounds. It was a mismatch.

Yet, Patterson got even in the rematch, however, a stunning left hook in the fifth round of a fight in New York’s Polo Grounds, separated Johansson from his senses, left him flat on his back, his foot twitching. Patterson’s win gave him back the heavyweight title he’d lost.

But when Patterson defended the crown against No. 1 contender Sonny Liston, it only took Sonny a single round to earn the crown. When Patterson begged for a rematch, promising he’d do better, he did. He lasted two seconds longer against Sonny, another ex-champ failing to regain the crown.

Liston himself joined that list, after losing the title to Cassius Clay (soon to be Muhammad Ali) in 1964, they rematched in Lewiston, Maine in a high school hockey arena and Liston lasted about as long as Floyd did, falling in a controversial first-round KO.

Muhammad Ali, who had his title taken away after refusing to go into the service, regained his title with his thrilling win against George Foreman in 1974. He regained it a third time, earning a decision over Leon Spinks in 1978 after his embarrassing loss to the toothless Leon the year before in a fight he never should have taken.

George Foreman also regained the title, long after he lost it to Muhammad Ali, knocking out Michael Moorer in 1994, twenty years after he lost it the first time.

As you can see, a few fighters have done it. Patterson, Ali, Foreman. Does Tyson Fury have what it takes to join the list and avenge the only loss of his career? Can Fury be the man to tell heavyweight history to go to hell? I’ll be watching to find out.