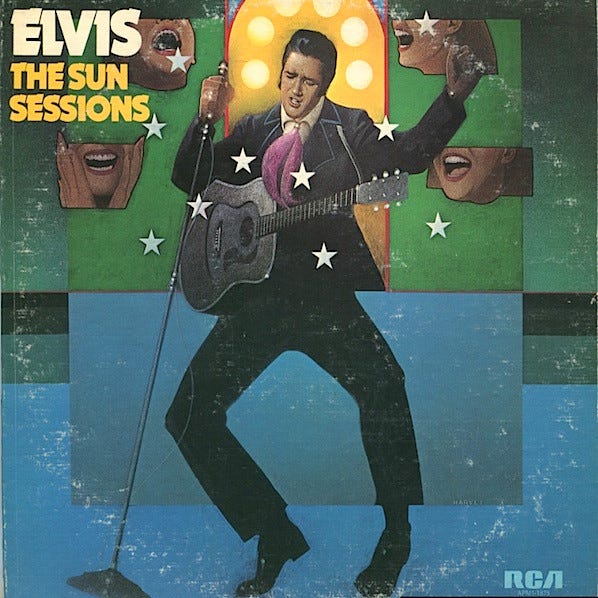

The earthquake called Elvis started today!

70 years ago in Memphis' Sun Studios, a truck driver cut a song, changed the world

The Internet tells us that there are two ways to measure an earthquake. One is to measure the magnitude or the size of it, another graphs the intensity of the eruption. As far as we know, nobody has ever brought a seismograph inside the dusty building at 706 Union Avenue in Memphis, Tennessee but if they had in the summer of 1954, it would have been interesting to see what it read when this soft-spoken truck driver showed up and over the next few months turned American popular music upside down.

An odd-shaped building with very unusually hand-tiled ceilings installed by Sam Phillips himself, Sun Studios is exactly what you might imagine a hole-in-the-wall studio looks like. There’s a tiny entrance area, barely wide enough for a desk, then in the actual studio area, barely enough room for three or four musicians, there’s an old piano in there with worn-out keys (probably thanks to the fingers of Jerry Lee Lewis), an assortment of black and white photos on the walls and on the tile floor, a little black “X” precisely where the microphone stood waiting for the sounds coming out of that truck driver’s pouty mouth.

The building used to be an automobile glass repair shop with a tin ceiling. After Phillips bought it, he installed acoustic tiles and, according to an article in Popular Mechanics, worked precisely to get the sound just so. Former Sun Studio engineer Corey Webber told the magazine “the sound changes depending on where you place instruments…even if you are moving them just a few feet.”

Visiting the actual studio a couple years ago, they conclude the tour by playing an original Sun Studio recording, in this case, Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes.” Everyone in the room, of course, had heard the song before, probably hundreds of times but here, it just leaped out of the speakers as if it actually belonged right there, which, of course, it did. It was created there, in the very spot where we all were standing and it occupied the air in a way that was arresting, rousing, thrilling.

As we listened and looked around, it wasn’t much of a leap to imagine yourself up in that control booth, hearing that tune for the first time, knowing you had a stone-cold, rock-solid, toe-tapping No. 1 hit! (It was actually Take Two!)

An X on Sun Studio’s floor marks where Elvis’ mike was set. Bob Dylan knelt and kissed it.

Go back about a year before “Blue Suede Shoes” and here is Sam Phillips up in the tiny control booth in the evening after Independence Day, 1954. Isn’t that fitting, right AFTER Independence Day? Elvis Presley was freed and in turn, freed all of us.

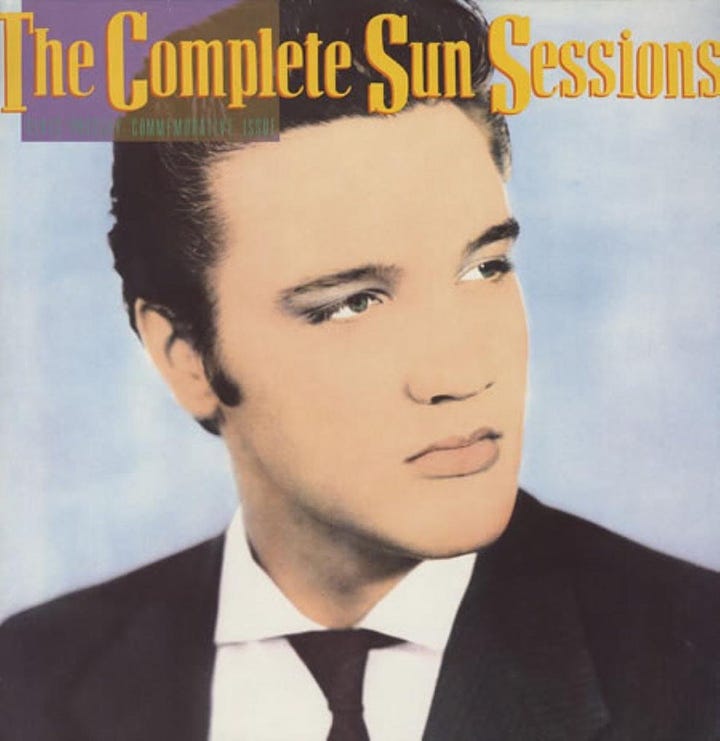

Below him, a 19-year-old Elvis Presley, a truck driver for Crown Electric with a passion for music, stands before the microphone, frustrated after running through his personal catalog of songs and not really impressing anybody. This was his chance and he was blowing it.

With time and patience running out, Elvis begins beating his guitar to an old blues tune he loved, “That’s All Right, Mama,” a simple, nondescript tune written by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, an African-American blues singer, someone that Phillips later admitted he was shocked Presley, a poor white kid, knew.

Phillips heard something in Presley’s spontaneous presentation, got bass player Bill Black and guitarist Scotty Moore to follow him and they ended up cutting the number as Elvis’s first Sun single. The song, as shocking a source for a revolutionary tune as you could imagine, was exactly that.

On the evening of July 8, that one-sided single came whistling out of radio speakers tuned to Dewey Phillips’ “Red, Hot and Blue” show on WHBQ and everything changed. As Peter Guralnick explained in the first half of his superb two-volume Presley biography “Last Train To Memphis,” the song was a hot connection. “The response was instantaneous,” he wrote. “Forty-seven phone calls, it was said, came in right away, along with fourteen telegrams? – he played the record seven times in a row, eleven times, seven times over the course of the program. In retrospect, it doesn’t really matter; it seemed all of Memphis was listening as Dewey kept up his non-stop patter…”

“Forty-seven phone calls, it was said, came in right away, along with fourteen telegrams? – he played the record seven times in a row, eleven times, seven times over the course of the program. - Immediate response to “That’s All Right”

Even now, 70 years later, the depth of such an immediate response to a record is startling. Can you imagine any song by any artist now or ever generating such an instant reaction, even with all the technological advantages we have available to us? It was as if entire cities all across America had kept their late-night radios on for years and years, hoping for some sort of sign or message of hope, excitement, jubilation, anything to shake things up.

The unusually shaped Sun Studios building in Memphis is where it all started.

Yet, here it came one warm summer night, out in the middle of the country, Memphis, Tennessee. And as Jerry Lee Lewis would later sing into that same Memphis microphone a year or two later, across the city there was “A Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On.” It was Elvis Presley.

You have to remember that in 1954, only a little over half the population owned TV sets. The Presley’s didn’t even have their own telephone line. Faceless, pictureless radio still ruled. You had to listen. And pay attention.

The Billboard charts showed America was listening to Elvis Presley. With five hit songs in 1956’s top 15 (“Heartbreak Hotel” – 1., “Don’t Be Cruel” – 2., “Hound Dog” – 5.), four in 1957 (“All Shook Up” – 1., “Too Much” – 9, “Teddy Bear” – 14, “Jailhouse Rock” – 16.) Elvis Presley was a phenomenon.

Almost before you knew it, here was this swiveling kid Presley on national TV, shakin’ his hips, sneering his way through an assortment of exciting, ground-breaking, earth-shakin’ tunes that shocked, thrilled, irritated, delighted viewers from coast to coast. Guralnick summed up precisely how it felt: “Elvis hit like a Pan-American flash.”

The impact of that Presleyquake was felt all over. In Freehold, New Jersey, a seven-year-old Bruce Springsteen was watching. He wrote about it in his memoir “Born To Run” as if it had happened the day before. “Ladies and gentlemen…Elvis Presley” Springsteen wrote, precisely remembering the moment. “Seventy million Americans that night were exposed to this hip-shakin human earthquake. A fearful nation was protected from itself by the CBS cameramen, who were told to shoot “the kid” only from the waist up. No money shots! No shifting, grinding, joyfully thrusting crotch shots. It didn’t matter. It was all there in his eyes, his face, the face of a Saturday night jukebox Dionysus, the shimmying eyebrows and rocking band. A riot ensued.”

In Hibbing, Minnesota, Robert Zimmerman, later to be known to the world as Bob Dylan, felt it, too. “When I first heard Elvis’ voice, I just knew that I wasn’t going to work for anybody; and nobody was going to be my boss,” he wrote. “Hearing him for the first time was like busting out of jail.”

Just outside of London, future Rolling Stone Keith Richards felt a similar jolt. “But the one that really turned me on, like an explosion one night, listening to Radio Luxembourg on my little radio when I was supposed to be in bed and asleep was “Heartbreak Hotel.” That was the stunner. I’d never heard it before, or anything like it. I’d never heard of Elvis before. It was almost as if I’d been waiting for it to happen. When I woke up the next day, I was a different guy.”

Over in Liverpool, England, John Lennon listened and knew his destiny, too. "Nothing really affected me until I heard Elvis,” he said. “If there hadn't been an Elvis, there wouldn't have been The Beatles. Before Elvis, there was nothing.”

Seventy years ago yesterday. In Sun Studios. In Memphis, Tennessee.