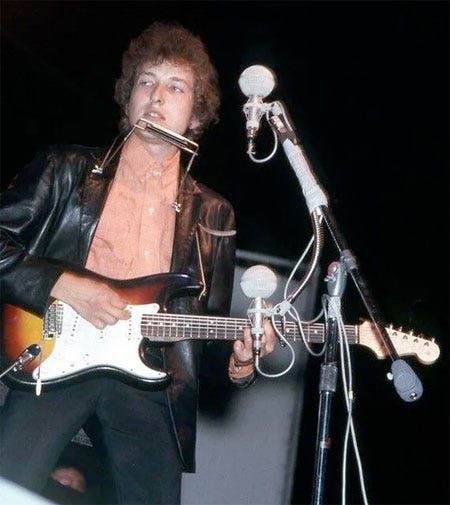

The "real" Bob at Newport, 1965

"The Other Side Of The Mirror" captures that crucial performance

In a few weeks, the re-creation will be among us. The sacrilege of our Bob Dylan playing electric music before the stunned masses at the Newport Folk Festival on July 25, 1965 will undoubtedly be the pivotal moment in “A Complete Unknown,” the new Dylan bio that hits the screens on Christmas day.

By my count, that’s actually the second filmed re-creation of the event. The first, memorably, came in Todd Haynes’ “I’m Not There” where we see a leather-jacketed Bob spin on the hostile audience sporting a submachine gun instead of a Stratocaster, which, if not literally true, may have been how it felt to the folk purists, aghast that their polemical songsmith ditched topical songs for what he hoped would be higher art.

He was right, of course, because if he wasn’t, if he hadn’t gone on to a remarkable career, gone on to win the Nobel Prize, Grammy Awards and all sorts of honors, he’d have been a temporary sensation, someone who occupied the national consciousness for a while, had nothing else interesting to say and sort of disappeared.

A few weeks before the film itself actually gets here — the hype has already arrived — it seemed like a good idea to re-watch the ACTUAL event itself, as filmed by Murray Lerner in his “The Other Side Of The Mirror,” a film that captures all of Bob’s Newport performances from 1963-1965. We’ll get to that in a moment.

As the film’s premiere approaches, it’s hard to say what’s more shocking; Bob giving the film and Timothee Chalamet’s performance and a mighty plug to Elijah Wald’s book or that he did all of that on Twitter/X.

“There’s a movie about me opening soon called A Complete Unknown (what a title!). Timothee Chalamet is starring in the lead role. Timmy’s a brilliant actor so I’m sure he’s going to be completely believable as me. Or a younger me. Or some other me. The film’s taken from Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric – a book that came out in 2015. It’s a fantastic retelling of events from the early ‘60s that led up to the fiasco at Newport. After you’ve seen the movie read the book.”

With an endorsement like that, we can assume that (A.) Bob likes how he’s portrayed in the film — we never heard a word about his reaction to the Todd Haynes’ film — (B,) he must have read and LIKED Elijah Wald’s book, which to my recollection is only the second time in memory where Bob has liked how he was written about.

The other was Anthony Scaduto’s “Dylan” where, near the end of the book, Dylan told him he liked it, then actually went to the point of explaining what he intended in some of the songs on “John Wesley Harding” which, from what I’ve read in doing the research for my three editions of “Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography 1961-2022,” he never did again. (The book is available on Amazon, if you’re interested.)

While it seems to me that Bob has been more than generous when it comes to talking about other performers’ work, he hasn’t said much specifically about books people have written about him — including mine. So getting that sort of encomium from the Nobel Prize-winner is to be cherished.

Looking at Lerner’s film once again, we forget that in 1965, Bob did a couple of daytime performances, three wind-blown acoustic/harmonica numbers at a workshop the day before. He performs “All I Really Wanna Do,” “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” and “Love Minus/Zero” pleasantly enough, his wild mass of brown curls blowin’ in the wind, so to speak. Lerner zooms in close and we see Newport’s favorite having filled out a little, now wearing a dark sport coat, smiling as he walks away from a standing ovation.

The next day, we see a different Bob, dark glasses on, wearing a wild polka-dot shirt and boots, fiddling with the organ during an afternoon rehearsal. According to pianist Barry Goldberg, he was playing Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.”

Later, a cigarette jammed in his mouth like a peg, he faces guitar whiz Mike Bloomfield as they try to tune up. A shirtless Peter Yarrow, that evening’s MC, hollers instructions all the while. Then, we see a brief clip of Dylan and the band (Sam Lay on drums, Jerome Arnold on bass, Al Kooper on organ and Barry Goldberg on piano) running through the changes of “Like A Rolling Stone.” So it wasn’t like Yarrow didn’t know what was coming.

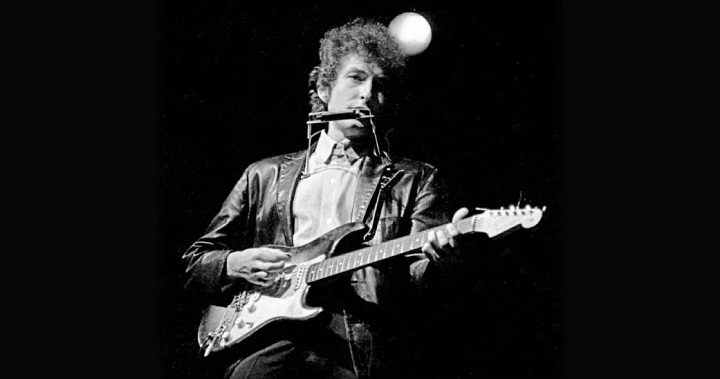

When we cut to the evening performance, Bob’s wearing a leather jacket, a high collar shirt, a Fender Stratocaster and his harmonica rack and a determined look as the band rocks into “Maggie’s Farm.”

The only band member in the spotlight, he strums the Strat relentlessly while Bloomfield burns roaring riffs off his Telecaster in the shadows off to his right. He looks around the stage but never directly at the audience. And as the song winds down, we can hear some of the boos over Bloomfield’s closing riffs.

Dylan shows no reaction as he sings the unknowingly (or knowingly) ironic words “I try my best to be like I am. But everybody wants you to be just like them. They say, ‘Sing while you slave’ I just get bored.”

The moment the song ends, there’s a tremendous roar of boos from the crowd, almost as if they were building up an explosion of sound once the electric noise subsided so they could be heard. Dylan seems oblivious to it all, tuning his guitar, not acknowledging what sounds like an overwhelmingly negative reaction as they prepare to go into “Like A Rolling Stone,” the song that’s probably Dylan’s most important -= if not best — which had been released as a single five days earlier. The song would climb all the way to No. 2 on its 12 weeks on the Billboard charts, a spot Dylan would, improbably surpass with his 17-minute “Murder Most Foul” some 55 years later.

While Dylan begins the opening chords, Bloomfield plays a wistful figure, not the slam-bang opening on the record. Bob keeps strumming his guitar, looking around the stage. Kooper’s organ comes through clearly in the mix as Bob recites the verses, trying to keep up with the surging verses, unlike, say, the way you’d hear him on the 1966 World Tour with The Hawks (later the Band) where, as Robbie Robertson once said they could “drill these songs into people.”

Of course, on this hot July night, Bob can’t know that this song he’s in the middle of will carry him through all these years as the pinnacle, what, as time goes on, will be seen as the high point of his long career. He’s trying to work his way through the song live, something he hasn’t done since he finished singing it in a Columbia recording studio on June 16, just 39 days ago.

As soon as he turns towards drummer Lay and concludes the song, both he and Bloomfield take their guitars off and leave the stage — after just two songs! Sniffing disaster, a panicked Yarrow, dark glasses still on, dashes to the microphone amid the boos, trying to explain the unexplainable.

“Bobby was…He will do another tune, I’m sure if we call him back.” The boos are louder, angrier. All the way to Newport for two overamplified songs?

“It was the fault of the…he was told he could only do a certain period of time,” Yarrow says, stalling as he turns off stage and not asks, begs.

“Bobby, can you do another song, please?”

“He’s going to get his axe,” he says. “He’s coming.”

He takes the dark glasses off, wipes the sweat — but not the panic — away.

“He’s gotta get an acoustic guitar.”

And then we see Bob, acoustic guitar on his shoulder, coming back on stage.

He immediately starts to strum “Mr. Tambourine Man,” everybody’s favorite, which might give us a sense of how that moment truly hit him. And several strums through the song, he realizes he doesn’t have the harmonica he needs for the key of the song.

“Does anybody have an E harmonica?” he asks. “Anybody? Just throw them all up.”

When they do, he picks one, puts it in his holder and says “Thank you very much” as he fixes a capo on the neck of his guitar and rolls into the lovely — and familiar —harmonica opening of of “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The crowd, just delighted to have gotten their way, cheers wildly and as Lerner’s camera pulls in for a deep closeup, we pause the DVD for a moment and take another look.

Though it is a hot night, there’s an unmistakable single streak of a teardrop on Bob’s left cheekbone. He HAD heard the boos, after all.

Without a pause, Dylan concludes the night’s performance and the festival itself, rolling directly into a song whose title now looks prophetic. With a mournful harmonica wail — no other introduction — he goes into a stunning “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” And singing with the ache of the evening’s events on him, this line seemed to carry even more import than usual.

“Whatever you wish to keep, you’d better grab it fast,” he sings. Before you knew it, he was gone.

Hi John,

One note: the booing you hear after "Maggie's Farm" in Lerner's film is not on the original soundtrack -- it is spliced in, from the wild booing after Dylan left the stage having played only three songs. The band was so loud that the stage mikes were turned way down during the performance, and virtually no crowd noise is audible until they finished "Rolling Stone" and Yarrow came back to the mike.

I look forward to reading your posts. Gotta admit, I was responding just to the pic in that last comment, intending to read the post later. At work now, where I should probably concentrate on other things. I have a dear friend who writes exclusively about Zimmm. Guessing you already know him. Try searching for Steven. I forget the rest, exactly, but something like "Got nobody to love." Tell him I told you to say hi. Pleasure crossing paths.