The Salinger finale - so far, anyway

"Hapworth 16, 1924" was published in the New Yorker in June of 1965.

For the past several nights, I’ve been watching Shane Salerno’s “Salinger,” his oft-criticized, much debated biography/documentary about American writer J.D. Salinger which came out in 2013, or three years after J.D. hit the dirt, which is a good thing because had he lived to see it, this might have done the trick.

Many of the claims Salerno made in the documentary, particularly about Salinger having a wealth of material that would shortly be released to the public, haven’t worked out yet. Salinger’s son Matt did a story with The Guardian in February of 2019, assuring that he was going through his father’s material and he said “most all of the stuff he wrote will at some point be shared with the people who loved reading his stuff.”

That was five years ago. So was Matt just saying that to get people to stop bugging him about his old man’s work or did he really mean it? How long does it take to re-read and organize and get some of his dad’s material out into print? Or, is that work so insular, so embarrassingly bad, that Matt would rather let his dad’s reputation survive as it is and keep that stuff private?

When it comes to posthumous work, it’s easy to see both sides. From what I’ve read, Franz Kafka insisted all his unpublished work be burned upon his death. It wasn’t. One of Ernest Hemingway’s most cherished later works was his recollections of his early days in Paris, “A Moveable Feast” which, happily, was released posthumously.

While you should respect the writer’s wishes, I suppose, if there is something that they left behind of quality, that’s distinctively, unmistakably his or hers, why just burn or discard it? Especially in the case of a writer who simply stopped publishing in 1965 but, from all accounts, including Salerno’s “Salinger” he wrote just about every damn day until his death in 2010.

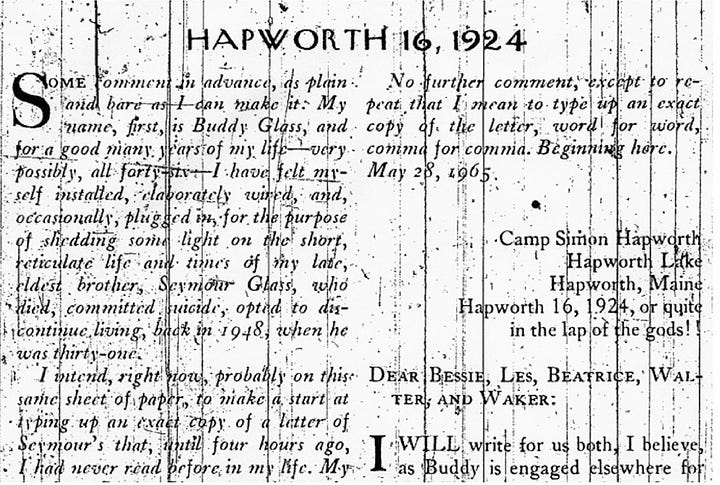

When it comes to Salinger and what he left behind, we can’t help but be a bit wary, even before we heard from his son five years back. Because the very last bit of Salinger writing that he was willing to share with the world was an amazingly long short story, almost a novella, called “Hapworth 16, 1924” that appeared in — and took up most of — The New Yorker issue of June 19, 1965.

And for a writer known for his subtle, careful touch — there’s an anecdote in “Salinger” about him holding a serious grudge over a New Yorker editor inserting a comma where he didn’t think one was required — “Hapworth” is about as dense and difficult to wade through as James Joyce’s “Finnegan’s Wake” or his “Ulysses.”

At 28,000 words, none of which, apparently, New Yorker editors were able to fiddle with, it is one tough read, one that I was never able to tackle until recently. I looked but could never find it because Salinger never allowed it to be reprinted. He almost did once with a small press but that fell through.

So, for the final 45 years of his life, one of America’s finest writers was as silent — in print anyway — as a Chesapeake Bay clam. Did the criticism of “Hapworth” — and there was plenty of it — shut him up? Or didn’t he have anything else left to say?

Salinger’s stubborn silence drove a lot of writers, some really good ones, nuts. The terrific Esquire writer Ron Rosenbaum made the pilgrimage to the little New Hampshire town where Salinger was holed up for a cover story, then felt guilty about it, as he probably should have.

Just because a writer once wrote something that just about everybody loved — “Catcher In The Rye” — did that mean he had to keep churning stuff out? We hadn’t really had a writer do that sort of thing until Salinger. Hemingway’s bearded face was on more magazine covers than practically anybody in his time and authors like Joseph Heller, John Updike, Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal weren’t exactly publicity shy. And after watching “Salinger,” you could understand why Salinger may well have wanted to be left alone.

Evidently, many of his readers took this passage from “Catcher” to heart: "What really knocks me out,“ Holden says, “is a book that, when you're all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it."

People did that, not just writers from Esquire or would-be biographers. And clearly, that drove Salinger crazy, maybe literally.

Writing for The Millions in 2015, Christian Kriticos took a long look at “Hapworth” and admitted he was as baffled as everyone else.

““Hapworth” is the final story (although the first chronologically) in Salinger’s Glass series, a sequence of short stories revolving around a family of hyper-intellectual New Yorkers,” he wrote. “One of the most common criticisms leveled against the Glass stories was that Salinger was writing them purely for himself, at the price of alienating his readers. Salinger even admitted as much, stating “I write just for myself and my own pleasure,” and “there is enough real danger, I suppose, that sooner or later, I’ll bog down, perhaps disappear entirely, in my own methods.”

“Thus,” Critikos writes, “Hapworth” came for many to represent the culmination of this, and the ultimate in insufferable self-indulgence, with its endless verbosity and preposterous length. Even within the story, Salinger appears to acknowledge this, with his narrator warning us that “This is going to be a very long letter!” and later urging the reader “Please, please, PLEASE do not grow impatient and ice cold to this letter because of its gathering length!”

When a writer, in re-reading his own work, applies the brakes, suggests that maybe he did run off at the mouth a bit but it’s too late to go back, start over, whittle it down, maybe he thinks: “I’m J.D. Salinger, for cryin’ out loud. I know what I’m doing. Back off.”

But maybe the isolation, his retreat from society, from the world of publishing, critical input and reader response ended up poisoning his work. That’s if the critical response to “Hapworth” was indeed on target.

The story is available online (link below) and I was even able to find a brave soul who offered an audio version on YouTube.

But since so much time has passed since the story’s publication, there is the possibility that Salinger’s technique as an author was so advanced, so ahead of the field, we just didn’t understand what he was doing. That wouldn’t be the first time an author’s work was misunderstood in its time. Ask Herman Melville about “Moby Dick” or Mark Twain about “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

Critikos suggest that perhaps “Salinger was “trying something new, arguably something different than any other American writer: to reconcile non-material (Eastern) ways of transcendence with the particulars of American daily life.” writer Roger Lathbury contends that this accounts for its unusual style — “a letter that is not a letter” — and that to write what Salinger wanted to write necessarily required “a seismic shift in sensibility.”

“Salinger addressed this exact concept in an earlier story entitled “Teddy,” which also takes a child prodigy with spiritual gifts as its protagonist: “It’s very hard to meditate and live a spiritual life in America.” Likewise, the form of “Hapworth” is recycled from an earlier unpublished story, “The Ocean Full of Bowling Balls,” which is also presented as a letter written home from summer camp.

“Thus, one might hypothesize that in “Hapworth” Buddy’s voice is apparent via a brief introduction before the letter begins, in which he assures us twice that he intends to type up an “exact copy,” which is what we will read. This over-assurance is immediately suspicious, and the opening line, in which Seymour states “I will write for us both,” might also serve as evidence.”

What if that is the case? What if Salinger had outdistanced his critics? Watching “Salinger” — with all its flaws and overdone bits — made me think about that.

As Critikos concludes: “This is the crux of “Hapworth” — it defies interpretation, and in this way stands as Salinger’s ultimate embodiment of the Glass family’s ideals. Just four years earlier he had admitted that Buddy was his “alter-ego,” blurring the lines between fiction and reality, and here we see him bringing the ideals of his fictional world into the reality of his work as a writer.

“In Franny and Zooey, Salinger quotes at length from Swami Prabhavananda:“You have the right to work, but for the work’s sake only. You have no right to the fruits of work.” “Hapworth” can be seen as a culmination of this ideal, as it represents Salinger writing purely for himself, and for the pleasure of the work. The fact that he continued to write for the rest of his life, but ceased publishing, also meant he was rejecting considerable “fruits.”

I’ve written about Salinger’s silence and his son’s apparent reluctance to share his posthumous work with us — so far at least. But what if, toiling away for his eyes only up in a New Hampshire bunker just 78.9 miles away from me, growing up in ol’ Brookline, he stumbled into a breakthrough in writing fiction and wasn’t able to tell a soul about it? He coulda called me!

So, are you brave enough to give “Hapworth 16, 1924” a try?

Here’s a link to the story that worked for me as well as an audio book version of “Hapworth 16 1924.” Keep in mind the audio version is over two hours, so fortify yourself with a drink and snacks if you want to give it a whirl. But if you do, please drop me a note and let me know what you think! Thanks, friends.

THE LINK: https://kaizenology.wordpress.com/2014/06/18/hapworth-16-1924-j-d-salinger/

THE AUDIO VERSION:

Harper Lee was similarly silent after writing To Kill a Mockingbird. It's not surprising that some authors only have a single, truly great novel in them (we should all be so lucky). After that, everything they write they consider pedestrian, so why publish it?

Like Salinger's later efforts, Harper Lee published Go See a Watchman in 2015 to mediocre reviews, at best.

I've read "Hapworth" twice, decades apart. The time between didn't make it any less of a slog to get through. But your essay was very insightful, thank you. There was a little book published in 1977 titled "Zen in the Art of J.D. Salinger" which traces the development and progression of Zen concepts in Salinger's writing. There are traces of it even in "Catcher" and the early short stories, according to the book. By "Hapworth" it was full-blown. So who knows how readable or publishable the post-"Hapworth" material is?