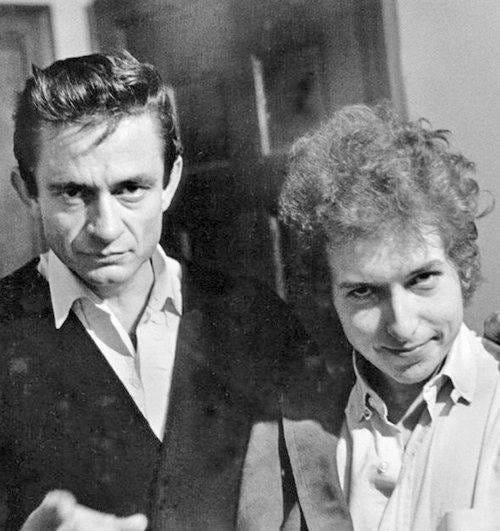

Editor’s Note: This is Part Two of the Bob Dylan playing Woodstock fantasy I came up with a long time ago. In Part One which I posted yesterday, Columbia’s John Hammond enlisted Johnny Cash to try to get Bob Dylan back writing and working again. Cash had a plan.

Bob Dylan at Woodstock (Part Two)

So, a couple of nights before John Sebastian would kick things off at that festival before an ever-growing sea of people, Cash and Hammond hatched their plan. It was Cash’s idea and Hammond quickly approved. They knew damn well that nobody was going to convince Bob Dylan to walk out onto the stage at Woodstock in front of half a million hippies, yippies, flip-ees and zip-ees.

But maybe – and this was Cash’s genius - somebody could talk him into NOT playing. This was the kind of scheme that would live on in rock and roll immortality. The single greatest no-show since Hank Williams missed that New Year’s gig a few years back for the most understandable of reasons.

Cash’s pitch was different. He and Bob were good friends now. And in some ways, Dylan was really in need of a good friend, someone who wouldn’t try to bullshit him. Both of them had been in Nashville’s Studio B lately, running into each other, Cash’s career seemingly steered by this faraway star, Dylan’s sort of under a cloud.

Johnny Cash had a devious plan for Bob Dylan for a hidden Woodstock show . Bob loved it.

So one evening, Cash made his pitch. Right away, he got Bob laughing. Dylan was sitting in the corner of Studio B by himself, some sheets of paper in front of him with some very small, painstaking handwriting on it. He’d been recording a slew of other people’s songs. But he never stopped scribbling.

“Bob, I know you’re going to think I’m crazy,” Cash said, walking in, laughing. “But I have an idea for the greatest damn prank of ‘em all. And I want you to help me.”

Dylan looked up. A prank. Hmmm. Interesting. “Go on,” he said.

“Well look,” Cash said. “I know they’ve been up your ass about this Bethel, Woodstock thing coming up,”

“Oh, Jesus….” Dylan said, waving his hand, “don’t even start.”

“I know, the voice of a generation and it’s your generation and all that…”

“MY Generation? Hey, that’s Peter Townshend!” Dylan said, pointing a finger at Cash, grinning. “Right, those are MY PEOPLE, the tie-dyed, long-haired, doped-up, do-nothings..the lost, forlorn, the stupid, the naked…”

“That’s them,” Cash laughed. “Sounds about right.”

“They can HAVE them,” Dylan said. “I don’t want ‘em. Well, maybe some of the naked,”

And the two of them laughed and Cash, a fisherman, felt as if he had a nibble.

“Well, what about THIS idea,” Cash said, sort of chuckling the way he did when he had a good one. “This is so damn diabolical, NOBODY would believe it. I mean, nobody. Shit, if we told Johnston about it, he’d stain his god-damn jeans.”

“They’re probably already stained – barbecue sauce, grease, beer,” Dylan quipped, staring at Cash intently, as if there was really something he wanted to hear.

Cash moved in closer and looked into Dylan’s eyes.

“What if you and I do a show – a PRIVATE show – I mean a really private gig…and we record the son of a bitch RIGHT BEHIND THE GODDAMN Woodstock stage, up in the hills. AND THEY DON’T KNOW A THING ABOUT IT?”

Dylan looked amazed.

“What?”

Then, like Bob Johnston talked about later, he put his hand on his chin and looked at the wall. Johnston was sitting over in a corner, quietly watching the two of them without saying a word.

“I mean it,” Cash continued. “Columbia has already given me the go-ahead for my next project, whatever I want to do. Hell, I’ve done two PRISON albums…so you think they’re going to mind you and I working together?”

Dylan, arms folded across his chest, hand to chin, was thinking hard. After a minute or two, he spun and asked, “But, like where? We gonna build a campfire or something?”

Cash put his hand up.

“Listen to this. I’ve been running this idea by Mr. Hammond. He’s connected. And when he found out where the main stage was going to be, he hired a couple of carpenters to throw up a nice little wood cottage for us, a nice little place that’ll be ready the last night of the concert. We can sneak in, relax and play for a while, record it and NOBODY will know a thing about it.”

“Right” Dylan was shaking his head.

Cash continued with the fervor of a convert.

“Hammond cleared it with Columbia already. I mean, they don’t know how big this festival is going to be – they have quite a lineup, Jimi, Sly, The Who, Janis…”

“Yeah,” Dylan said. “Robbie said The Band is playing there, too. That Lang guy came by and invited me...” And then he shrugged. Dylan seemed somewhere else, like he was really imagining it. Cash was up and walking around the studio.

“Think about it. What if you and I sneak up there in the middle of the night – they’ll be all tripping and everything…,”

“Yeah,” Dylan said, slyly. “I’m sure many of ‘em are going to be saying they saw me anyway,”

“Right,” Cash laughed, getting a stronger sense that Dylan WAS buying in. “You and I can sit there, do a nice little acoustic set – whatever you want – record it and shit, there won’t be a soul in the world who won’t wish they were there. Hell, I’d want to buy that record myself.”

“What kinda songs do you want to do?” he said. “I’ve been recording a few of other people’s songs lately, you know.”

“You can do whatever you want. Hammond said so already. And you know, I get how you like to work, Bob. What do you think it was like at Sun? Sam wanted something inspired, something that maybe you hit one time…So we played, had fun, got crazy and found things.”

“Like with Elvis?”

“Well, Elvis, he said, was a little bit different thing. He had to kind of steer that one because nobody was singing country like Elvis did. I mean, he was mapping the territory, kind of, you know. Elvis wasn’t thinking about singing no rock and roll, that’s for sure.”

It was quiet for a moment.

“How do you think Sam would record me?” Dylan asked. Cash wasn’t expecting that one. Before he could answer, Dylan began to strum his guitar. “Toooo-morrrow niiiiiight, won’t you be with me tonight,” he sang and Cash nodded in recognition. “Sam cut Elvis on that,” Cash said. “Some Johnson fella?”

“Tommy Johnson,” Dylan corrected. “Not Robert. Sam could have really done something with Robert Johnson. That’s if he didn’t mind bailing him out of jail.”

‘He offered to bail me,” Cash said. “Thing about Sam, if there was talent there, he’d do it. Guy was cheap but Jesus, he could see things and envision things. Maybe we should invite Sam. He ain’t working.”

“Would he come?” Dylan asked, suddenly and surprisingly intrigued.

“Sam don’t do nothing he don’t want to,” Cash said. “But if he heard us together, I bet he’d come. Woodstock Hideway. Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash, produced by Sam Phillips! I can see the headline in Rolling Stone Magazine now.”

Dylan was excited. The two of them were laughing and Johnston could see dollar signs. This was going to be something…

“How you gonna keep this quiet?” said Dylan, ever suspicious. “I mean, I can’t take a shit without somebody wanting to paw through it to see if I’m on dope or what I’ve been reading or…” He was getting wound up. Cash expected it.

“Look….NOBODY knows. Hammond, you and me. Johnston over there, who ain’t doing a thing right now. Christ, I can get my roadies to set it up for us. We’ll tell ‘em it’s my Counter-Country Album – do my warped-style rock like I did at Sun. They’ll eat it up.”

“You been drinkin?” Dylan laughed. And Cash knew he had him. Felt the pull on the line, so to speak.

“You know…I gotta say, I gotta admit, it’s a great idea,” Dylan said with genuine enthusiasm and surprise and delight. “Won’t that piss those fucking hippies off….think what they MISSED.”

Cash just smiled.

***

John Hammond had been at work on his end. He loved Thoreau and knew Bob would fall in love with his singularity, his vision and his independence if he started “Walden.” You couldn’t rush through that book. E.B. White called it “indigestible.” That was a good word. It was just the kind of book, Hammond figured, would inspire Bob, would get him excited about his work, his vision. Thoreau would get under his skin. He just felt it.

Once Hammond found out the site of the Bethel Festival, he hired two carpenters to construct a small Walden Pond replica house back out in the woods, way out behind the stage. He couldn’t make it the precise size – that would be too small. But it was proportional.

And he made sure the only thing that Dylan and Cash would find in there was a drum. A single drum. To echo Thoreau’s famous quote about a guy not keeping up with his companions “because he hears the sound of a different drum.”

Commerce was part of it, sure. But Columbia was in a good place, as strong as the label had been in years. This was time, maybe THE time, to step in a different direction. Maybe the right artist, the right set of songs, the air was filled with this kind of talking, thinking anyway, if only someone could gather it all…

And the more Hammond thought about it, wondered how Dylan would feel as he heard the sounds of the Bethel show would waft over the forest, a rich, explosive tapestry of sound cloaking a cabin where inside, even more powerful, secret, mystical sounds were emerging, surging up out of the earth, a real Earth Day.

Yet at the same time, none of them, none of those half a million kids, not a single one, would know where Bob Dylan was AT THAT MOMENT! Or hear him. And when they found out what they had missed later on…the furor would be unbelieveable. “We coulda seen DYLAN? What kind of crap is that? He was THERE?”

In a way, Hammond thought, there was something perfect about this. They didn’t REALLY listen to Dylan, or maybe didn’t appreciate him like they should have or VALUED him – that’s the word, value. Because Dylan’s VALUE to music, to teen-agers, adults, America alike was that he wanted, maybe even expected his audience to listen. That was what he found so great in England. You could see it on the “Don’t Look Back” tour. He stepped out into that spotlight, onto those stages of those old music halls and it was silent. Utterly silent. They came to listen.

When an artist, a sensitive, plugged-in artist like Dylan senses that, he delivers. That was why, a year later, when a disillusioned (and sadly mistaken) fan reached the breaking point and shouted the most famous cat call in rock history “Judas!” you could hear him, in Chuck Berry’s famous phrase “like he was ringing a bell.”

Now, with the biggest and most transformative musical festival of all time about to be blaring on just a few feet away, the counterculture’s greatest hero would be offering a new tune, several of ‘em, actually, just out of their reach. How delightful!

***

When the helicopter landed quietly in the woods, having flown over the entire Woodstock expanse, Dylan was smiling. He was above all the mud, the mess, the absolute sea of people below, literally and figuratively, the place looked like a huge city of tie-dyed ants. The Woodstock Generation. The hippies. His people. Looked like they needed a shower not more free love.

As the helicopter touched down, Dylan was excited. He walked towards the cabin, carrying his Martin 0-18 acoustic guitar and a small notebook and, as he crunched through the woods, snapping twigs that Natty Bumpo had to hear, he felt like he was getting away with something. Something exciting, almost like a James Bond mission. Cash was already inside with Johnston.

As Dylan pulled at the door of the cabin, he could hear their laughter. This was going to be fun. Though it was 90 degrees and had been rainy, it was dark and cool inside the wooden cabin, a few small, quiet fans in either corner stirring the air around. The high-backed chairs were wood – all wood – and turned so that Cash, near the door, and Dylan could face each other when they sang.

Johnston, who had recorded both of them before, had everything miked perfectly. On just the little sample playback he did with Cash just prior to Dylan’s arrival – Cash did an acoustic version of a song he and Bob wrote together - “Wanted Man” - there was something fundamental there in that space, something real and honest that seemed to cut through the heart of a generation of excesses happening just a few hundred feet away. The sound was great. It seemed to be coming out of the Earth.

There wasn’t going to be any studio trickery, or overdubs and or take sixes. Sgt. Pepper’s my ass. What could these two giants generate with minimal accompaniment? What sound would emerge?

Johnston, who always said Dylan had a different voice for every album, was anxious to find out. Dylan stood in the doorway, taking it all in. He saw that the trusty old Ampex 602 tape recorder, the one Garth Hudson had used to record The Basement Tapes, was also set up, ready to go whenever Johnny and Bob started. Dylan spotted it when he opened the door and smiled liked he was greeting an old friend.

“Is this gonna be as big as Folsom?” Dylan giggled as he stood in the doorway and saw Cash approaching him with a smile and a big oatmeal cookie.

“If Johnston doesn’t fuck it up,” Cash thundered in that rich baritone, looking at Johnston, sitting over by the cookies, his feet up.

“Just us?” Dylan asked, walking over where Johnston was.

“Yup,” Johnston said in his best high-pitched, ‘you wanna make something of it’ twang. “Shit, nobody wants to play with a pair of protest singers.”

Dylan laughed and Cash threw the rest of his cookie at Johnston.

“It’s up to y’all,” Johnston said. “I’m just gonna turn on the fucking tape recorder and eat oatmeal raisin cookies. These sumbitches are good!”

“You know what we should do?” Dylan said, climbing up into the chair. “We should each do each other’s favorite songs. Together.”

“Like ‘Johnny Cash Sings The Bob Dylan Songbook?’ Cash said, gently hinting at his current status as THE world’s biggest music star. “That would hit the charts?”

“Yeah,” Dylan said, giggling, thinking of the royalties an album like that would bring. “Except I’ll pick the songs for you. We’ll start with ‘Sad-Eyed Lady’”

“I could sing that song,” Cash said, “Sad-eyed lady of the LOOOOOOOOOWlands” letting his bass voice almost drop below the range of human hearing.”

“Really,” Dylan said. “It’d be fun. And we know the words,”

“Speak for yourself,” Cash said. “And you get a huge break there, Bob. Christ, I only know 47 words. And that don’t include shit and damn.”

“Forty-seven words? That’s verse one for Bob Dylan!” Johnston, sitting up straight, applauded. “Let’s do it,” he said.

“What do you want to start with?” Dylan began to strum, “Well…I taught the weeping willow how to cry…” He stopped. “You know, that’s a great line. I wish I wrote that.” Cash, flattered, smiled and nodded. Then he began to sing himself,

“Well, it ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, babe?...”

“You did that already,” Dylan said. “Let’s make it songs we haven’t done before.”

Cash shrugged. “OK by me.”

“Maybe it should be songs that we think the OTHER guy ought to sing,” Johnston piped in.

“Christ, give me a chance, Johnston,” Cash said. “I have about 40 songs, he has 400.” “Well, get off your ass then,” Dylan said, eyeing Cash. “We got all night.”

The two of them looked at each other and began to laugh.

“Tiny,” Johnston said, chewing on another cookie. “Do Tiny, Bob. Johnny could do that one”

A Basement Tapes song, “Tiny Montgomery” was obscure all right. But with Garth Hudson’s swirling organ, Dylan’s rockin’ on the front porch vocal…it was a Basement Tapes song that was so friendly, so inviting, to downright neighborly, it was mesmerizing. It was community.

“How’s it go?” Cash asked. And Dylan started to sing in his not-quite Nashville Skyline, warm and sharp and friendly voice,

“You can tell everybody down in ol’ Frisco, Tiny Montgomery says hello…” Two hogs, a buzzard and a crow, tell ‘em all Montgomery says hello…”

He finished the song.

“You wrote that?” Cash asked?

“I can sing that!”

“Show me,” Dylan cracked, laughing again. And Cash, flipping through the lyric sheet Johnston brought, began reciting the lyrics out loud, just about laughing at each line. And when he got to the line “Tell ‘em all Montgomery says hello.” Dylan and Johnston looked at each other and smiled. This was going to work. It was as if that song’s hello was a benediction, a special blessing that would mean the world to whomever it was directed to, a call to a real community, not a bunch of drugged up, tie-dyed space cadets running full-tilt from society, the real world, life.

This was deeper, real and tangible. And in Johnny Cash’s varnished voice, those words would sound like they tumbled down the side of a mountain. Cash thought it was perfect. It only took a few moments to get the rhythm down – Cash learned that from Sam, you had to have the right tempo.

“He was a tempo maniac” he told Dylan. Then once he started and hit it just right, the song flowed out of him, Dylan alternating verses, the two of them barely containing their delight at being able to work together.

“Wanna listen back?” wondered Johnston, obviously excited.

“Naw, let’s get a few down, then we will,” Dylan said. Cash looked at Johnston and winked. And the session began.

“What else you got from them? You did those with The Band, right?”Cash asked.

“Well, no Levon for most of it, but yeah,” Dylan said, fingering his guitar. “At Big Pink, at my place, it was always fun. Johnny, try this one…

“Everybody’s building ships and boats,” Dylan began to sing in his best “You don’t – and won’t – ever know if I really MEAN this” Nashville Skyline voice, tapping his foot. “…you’ll not see nothing but The Mighty Quinn…”

Cash laughed out loud.

“Love it! I love it!”

Johnston kept the tape running the whole time, catching the playful banter between the two as they ran down an impressive run of songs, some by Dylan, some by others, even some old Sun cuts. It was quite a song list: • “All-American Boy” • “Belchazzar” • “I Forgot To Remember To Forget” • “Girl From The North Country” • “Mama, You’ve Been On My Mind” • “One Too Many Mornings” • “I Don’t Hurt Anymore” • “Tomorrow Night”

They were having so much fun, Johnston was loving everything they did. He did what a good producer should do when things are flowing – shut up. The two guitars were in tune, both players adapted quickly to covering the songs themselves – they were used to backup bands, of course.

But the sound between the two, the light and chiaroscuro Dylan voice and the deep-pitched Cash rumble, blended surprisingly well and the affection between the two, even in mid-song was apparent.

“I’m right from my side, you know, Bob” Cash sang on “One Too Many Mornings”

“I know it, Johnny,” Dylan responded, a smile creeping across his face as they sat before the mikes. It seemed so unusual to see Dylan smiling in the studio. They had themselves an album.

The two decided to take a break. They walked outside and, off in the distance at the Woodstock Festival, could hear the sounds of Johnny Winter’s snarling electric guitar wailing into the New York night. Cash, smoking a cigarette, Dylan looking out into the night, listening to the sounds way off in the distance, began to laugh.

“We’ve got some good cuts,” he said. “We shoulda done some of these on your show.” Cash smiled.

“Well, you can always come on again, you know…”

Tapping his foot, looking at the ground, Dylan nodded. Then looked up. There was noise coming through the woods.

Trudging through the woods, here came Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm from the darkness. Beers in hand, a six-pack of Genessee each, here came Rick Danko and Richard Manuel with Garth Hudson, looking up absently at the stars, in tow.

“Doin’ some recording?” Levon quipped. “I hear you could use a hand?”

That god damn Johnston, Cash thought. He thinks of everything. After exchanging hugs and greetings, Robertson looked straight at Dylan and shook his head.

“We need to make some noise,” Robertson said. “I feel like I just played a bar mitzvah.”

Dylan did a double take

“What are you talking about, Robbie?” Dylan laughed.

“At this Woodstock Festival deal. Christ, they put us on between Alvin Lee and Ten Years After – he was speeding and Jesus, he was all over the guitar and, well, you can probably hear him off in the distance, Johnny Winter and his blasting Texas blues,” Robertson said. “Compared to them, we were, well, Richard said just call us “The Choirboys.”

“Damn, I felt like we didn’t even have the amps turned on,” Levon said. “Not how we wanted it.”

Johnston, who had masterminded this surprise visit to coincide with when he figured that Cash and Dylan would be taking a break, was just tapping his feet. This was going to be something. He knew The Band wanted to keep playing…and now Dylan and Cash were ready to resume…wow.

***

Johnston hurriedly got their equipment set up while Cash and Robbie talked with Levon and the rest of the crew. He put out some more cookies and beer and told the engineers to keep everything running. It was a good call.

Once inside, Dylan put on an electric guitar and yelled over to Levon.

“Let’s show Johnny how he should have done “Folsom,” and with Robertson’s lead – they had played this during The Basement Tapes, they soared into a faster, more rhythmic version of the Cash classic. It was different not hearing the clippedy-clop backing of the Tennessee Two but the song was still cool. Cash was nodding his head and smiling as Dylan snarled out the words.

“It’s a different song,” Cash said. And they were off, running through all sorts of songs, Dylan singing, Cash singing, harmonizing with The Band. It was a magical night. As Johnston wrote down the songs on the chart sheet, he could hardly believe the titles he was writing down, never mind what he was listening to. • “Big River” • “Train Of Love” • “I Don’t Believe You” – with Cash singing it, slyly, like someone who’d had his fill of groupies and one-]night flings. • “Obviously Five Believers” with Cash singing the last verse “Yes, I could make it without you…if I did not feel so all alone…” • “Wanted Man” • “Promised Land” • “Nadine” • “Slippin’ And A Slidin’” • \“Tombstone Blues” with Cash intoning the chorus “Mama’s in the factory, she ain’t got no shoes...” • “I Shall Be Released” with all of them singing harmony. • “I Still Miss Someone” – same thing. • “Get Rhythm” – everybody was clapping and loving it.

Bob Dylan always loved playing with The Band, but this was special…

Then Cash had an idea. “Bob…what do you think about this…let The Band start with the intro to “Like A Rolling Stone” – you know that dramatic, hard-charging beginning, then, as the first verse comes in, let it get real quiet, I mean, really clear out the air, then let the voice come in…and I’ll talk the first line like a damn country preacher.

“Once upon a time, you dressed SO fine, didn’t you?”

The Band – and Dylan – looked around at each other. Now this would be cool.

“Bob, you come in on the second verse,” Cash said, “and we’ll go that way until the final verse where we’ll take turns singing the “How does it feel?” part…until everybody goes nuts.”

Dylan was smiling, as if he had an inside secret cooking.

“Sounds great, Johnny. Let’s do it.”

With Garth Hudson kicking it off, the song had never sounds more magisterial, more powerful, more imposing and exciting. Johnston was standing up, directing each of The Band’s dramatic flourishes, even though nobody was paying any attention to him. “How does it feeeeeeeeeeeel?” Dylan sang…

“How DOES it feel?” Cash sang… “How does it feel” they both sang into the night. Johnston just made sure the tape kept running.

***

Back at Columbia Studio A in Nashville the next night, Johnston sat back and listened to all he had in a room by himself. He kept laughing and smiling. Great songs, great spirit, a great sampling of the best of each guy, delivered with sass and subtlety and artistry.

And to think, not one soul of those half a million tie-dyed kids knew anything about it. They thought Woodstock was big, was monumental. Wait until they hear this. This was the one that got away. This is the one that they’ll really want to LISTEN to. That was the thing. Get them to listen.

On Monday morning in New York, when Rachel came into the 11th floor office, there was a package on Hammond’s desk. It smelled like wood. When Hammond came in and picked it up, he seemed surprised and excited, all at once. She heard him unwrap it, then open his cassette player and click it in.

The lone voice, the pealing harmonica, the lone guitar floated out of Hammond’s office and drifted down the hall.

“Build your castles in the air and build ‘em high, too many people don’t even wanna try……the highways of the world are crammed and jammed, people goin’ nowhere for no reason. It’s a brand new world, a brand new season…You know what’s right, you know what’s wrong. Find that beat, that different drum…never mind the rest, you might be the one…”

She couldn’t make out all the words but that was OK. The message came through. It was no country song. John Hammond was drumming on his desk. She could hear the cassette player rewinding.

EDITOR’S NOTE: It sure would have been fun if this really happened. Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash DID actually record together, thanks to Bob Johnston’s scheme. It’s a very liquid recording session — you can hear the results on Bob Dylan (featuring Johnny Cash) – Travelin’ Thru, 1967 – 1969: The Bootleg Series Vol. 15. Thanks for indulging me! (Nogo)

I wish it did happen just as you imagined it did.