EDITOR’S NOTE: I happened to spot something on the Internet the other day regarding the apparently delicate health of Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame Carl Yastrzemski, now 85, which I cannot confirm and hope is just a rumor. Growing up in New Hampshire, getting to see Yaz in a Red Sox uniform for 23 seasons was an integral part of my every summer.

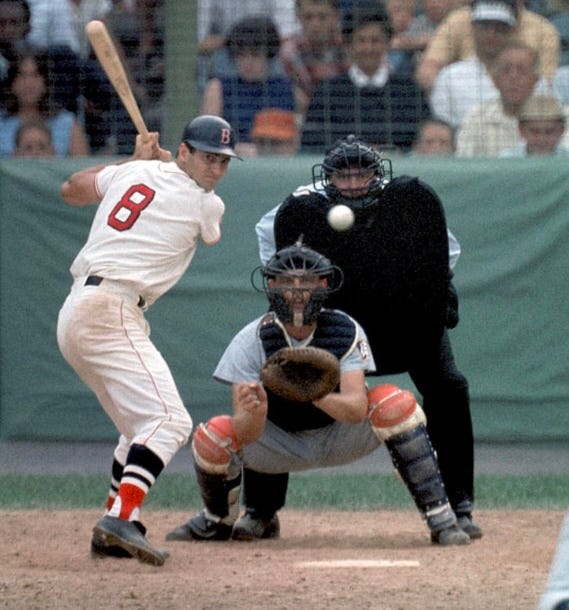

With a name like mine, I had a coach once call me “Ski,” how could I not root for the driven Yastrzemski? My son wore No. 8 for much of his youth baseball days. In recent days, occasionally catching Red Sox highlights from years ago, Yaz always seemed to be hitting a clutch two-run homer somewhere to save the day. He homered off Ron Guidry in that black day in Boston in the 1978 playoff game with the Yankees when Rich “Goose” Gossage got him to pop out to third to end the day. For some players, Fred Lynn, Ken Griffey Jr., Willie Mays, the game seemed effortless, they were naturals, they seemed born to play this game. It never looked that way for Yaz, one of the greatest grinders in baseball history.

Since he’s been on my mind lately, I thought I’d share my account of his final game, a chapter from my baseball book “Last Time Out” which documents the MLB finales of 43 all-time greats and the first MLB game for my son, John Nogowski Jr. with the St. Louis Cardinals in 2020. “Last Time Out,” if you’re interested, is available on Amazon and locally at Barnes & Noble and Books A Million. Let’s all hope Captain Carl is hanging in there.

CARL YASTRZEMSKI: To Yaz, with Love (1983)

DATE: October 2, 1983

SITE: Fenway Park, Boston, Massachusetts

PITCHER: Dan Spillner of the Cleveland Indians

RESULT: Pop out to second baseman Jack Perconte

BOSTON —He looked down at his feet, planted in the same batter’s box, maybe in the exact location where his predecessor had bowed out so memorably 23 years earlier.

Talk about following in Ted Williams’s footsteps. Carl Yastrzemski literally did. Now, it was all over. After 23 years, 3,308 games, 11,988 at bats—4,282 more than Ted Williams—3,419 hits and 1,845 walks, he was finally through.

With this last at-bat against Cleveland reliever Dan Spillner, a nondescript righthander finishing a grand 2-9 season, Yaz would wrap it all up. It was hard to focus the way he normally wanted to. The moment he stepped out of the Red Sox dugout, the crowd began to clap and wouldn’t stop, even for the public address announcer.

Yastrzemski stood outside the batter’s box, his bat by his side, his right arm waving his helmet to the overflow crowd that couldn’t throw enough love his way. They knew this was it; they’d never see No. 8 in that batter’s box again. Then he had to step in and try to hit.

How different a finish it was for him compared to Williams. On Teddy Ballgame’s final game—which wasn’t announced in advance—there was a brief pregame ceremony on a September day 23 years ago. Williams then merely went through the motions of another drab ballgame. It only became electric when Williams came to bat for the final time, in the eighth.

Even after Ted’s dramatic last at-bat home run, there was no nod to the fans, no final tip of the cap, nothing for them but the thrill of the moment, which, of course, has grown with the years.

Like the attendance, no doubt. But on this final day of reckoning, Yaz did beat Williams there. Ted drew just 10,454 to his Wednesday afternoon finale. There were 33,491 there for the Sunday afternoon farewell to Yaz. In fact, Yaz’s final weekend was a pure fan fest. Sure, there had been a time when Yaz had heard their boos, when he stuffed cotton in his ears when he ran out to left field. Boston’s fans can be demanding and very hard to please. Some of them thought Yaz should have won the Triple Crown and been the American’s League’s MVP every season from 1967 to 1983.

Instead, after that Impossible Dream season of 1967, it took him eight years to get the Red Sox back into the World Series. So if he’d heard more than his share of boos and took more than his share of blame in the newspapers and on the radio talk shows over that time, he understood, at last, how much they cared. So did he.

Together, they came through the years, through all the stances and heartache and strains and bruises and disappointments. This hard-won audience finally loved him. He loved them, too.

You could see it as he stood there waving his helmet, turning as if to drink in all the sad and happy faces that showered him with such affection. They had noticed how long and how hard he’d kept at it. How much of himself—and his life, really—he gave to this team.

So the day of reckoning was healthy. No, he never quite matched Williams’s standards of excellence at the plate. It wasn’t for lack of trying. How he worked at it. All those hours and hours of extra hitting. At least a dozen different stances. And worry. All those off-hours thinking about that next at-bat, that next game, that next pitch.

No, it was never easy for him. Never looked it, either. Maybe the great Ted Williams could study the enemy, declare that the dumbest guy in the ballpark was always the pitcher, come to the park and get his two hits every day. You’d never hear Yaz say something like that. He could see the lines in his face when he got dressed before this last ballgame. Deep circles under his eyes. He could see the silver feathering in the sides of his thick brown hair. He looked like a man who worked hard for a living.

“The pervasive, unshakeable image of Carl Yastrzemski that I carry inside me,” wrote Roger Angell in 1983, “is of his making an out in a game, in some demanding or critical situation—a pop-up instead of a base hit, or perhaps an easy grounder chopped toward a waiting infielder—with Yaz dropping his head in sudden disappointment and self-disgust as he flips the bat away and starts up the line, his chance gone again.

“No other great ballplayer I have seen was more burdened by the difficulties of this most unforgiving of all sports,” Angell continued, “and by the ceaseless demands he made on his own skills, and by the expectations we had of him in every game and almost every at-bat. . . . Yaz wasn’t glum, he was funereal.”

Why? Why could someone who could play the game so well be so downhearted about it? Well, he never came right out and said it, but how do you step into the batter’s box that Ted Williams had made his for 20 seasons?

So now, here it was. His final at-bat. Everybody remembered how Williams went out. What would Yaz do?

All New England knew his mannerisms as he stepped in. The hitch at the back of the pants, the jamming of the blue batting helmet down on his head with the palm of his hand, the twirl of the bat, the front foot poised. . . .

He laughed as he thought about that unmistakable voice he used to hear all the time every spring . . . Williams. “That damn Yastrzemski; he’s always got 15 million things to do before he gets into the batter’s box.”

No, he wasn’t another Ted Williams. But who the hell was? As you saw him standing at the plate on this sunny final Sunday, he was showing a little more of his back to the pitcher than he had before, the bat partially hidden by his body. Once he held the bat so high over his head, it looked as if he was trying to poke a cloud.

Now, it was as if age and gravity had finally brought his hands and tools down to a level more befitting a 44-year-old man. He didn’t look threatening any more.

There was a time when he cocked those hands and ripped that bat through the strike zone with a dramatic, back-bending flourish that would sometimes move classically understated Red Sox announcer Ned Martin to blurt, “Mercy!” One writer said Yastrzemski had a chiropractor’s dream of a swing. That was it, ferocious, at his best, almost untamed, out of control.

After his sudden surge of power in 1967—he hit 44 home runs—the stance seemed to change annually, a concession to age, to the way they happened to be pitching him that season, to a whim.

That was another element that further separated him from Williams, whose stance was defiant, his swing classical, elegant, unchanging through the seasons. Unlike Williams who played left field except for his rookie season, Yastrzemski started in left but eventually moved to first base, then designated hitter, still hitting in the productive spots in the Red Sox lineup. Williams just about always hit third.

Like Williams, he wasn’t able to bring home a World Series title, either. But, unlike Ted, in Yaz’s two tries, 1967 and 1975, both were seven-game series and he hit like hell (.400 vs. the Cardinals, .310 vs. the Cincinnati Reds).

Like Williams, he was great in All-Star games, too. Always found a way to raise his game when it counted. That’s what Boston fans just knew. They didn’t need stats to tell them. The Boston writers dug them up anyway. In the 22 most important games of his career—World Series, pennant races, playoffs—Yastrzemski batted .417, nearly 140 points higher than his lifetime average or about twice what Williams hit vs. St. Louis in his 1946 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Yaz was also the man at the plate when both those World Series ended. He flied out against Bob Gibson in Game Seven of the 1967 World Series and flied out against Will McEnaney in Game Seven of the 1975 World Series. His most famous final out came in the Red Sox-Yankees 1978 playoff game, when Goose Gossage got him to pop out to Craig Nettles, ending the game in utter heartbreak for Boston fans, who’d had a huge lead that season, then squandered it, losing a playoff game at home.

For stunned Red Sox fans, it just didn’t seem as if it really happened, as if it should have counted. Globe columnist Ray Fitzgerald, writing moments after he saw the ball descend into Craig Nettles’s glove, said “Somewhere there should be a film director wearing a beret and shouting through the megaphone: “Another take, gentlemen, and this time, let’s get it right.”

Angell, a Red Sox devotee, was wounded to the core. Writing about the moment in “Late Innings” he brought the moment back vividly.

“Two out and the tying run on third. Yastrzemski up. A whole season, thousands of innings, had gone into this tableau. My hands were trembling. The faces around me looked haggard. Gossage, the enormous pitcher, reared and threw a fastball. Ball one. He flailed and fired again, and Yastrzemski swung and popped the ball into very short left field foul ground, where Graig Nettles, backing up, made the easy out. It was over.

“Afterward, Yaz wept in the training room, away from the reporters. In the biggest ballgame of his life, he had homered and singled and had driven in two runs, but almost no one would remember that. He is 39 years old, and he has never played on a world championship team; it is the one remaining goal of his career. He emerged after a while, dry-eyed, and sat by his locker and answered our questions quietly. He looked old. He looked fifty.”

The scene so moved Angell, he even directed a criticism upward. A Harvard professor had written: “The hero must go under at last, after prodigious deeds, to be remembered and immortal and to have poets sing his tale.”

“I understand that,” Angell wrote, “and I will sing the tale of Yaz always, but I still don’t understand why it couldn’t have been arranged for him to single to right center, or to double off the wall. I’d have sung that, too. I think God was shelling a peanut.”

A couple years later, after Gossage had surrendered a game-winning home run to George Brett in the AL playoffs, writer Peter Gammons asked him about the pitch and Brett’s final swing. What was it like, surrendering that game-winning home run?

He was surprised at Gossage’s answer. “I think of Yaz,” Gossage said. “I’d like to think of these moments as the best against the best, not winners and losers. The pitch to Yaz ran a little more than the pitch to Brett. Don’t ask me why because I don’t know. If time were called and we went back and I had to throw those pitches over again, George might pop up and Yaz might have hit the ball into the bleachers.”

This was it. No time for a pop-up. His last at-bat, competing with the ghost of Williams. Ol’ Ted had gotten it right in his final turn at bat. Could Yaz follow him there, too? That was on the mind of every soul inside Fenway Park. Every player on either team knew what was on Yaz’s mind. So, of course, did Spillner, winding down a rotten season.

As reported in the Boston Globe the next day, Spillner already knew what the rules were for Yaz’s last at-bat. “We were in the bar with the umpires Friday night and Rich Garcia told us, ‘Look, fellows, if he doesn’t swing, it’s a ball,’ said Tribe pitcher Lary Sorensen.

With all that going on around him, the emotion of the moment got to Spillner, not exactly a precision pitcher on his best day. Once Yaz stepped in, he couldn’t find the plate.

Ball one. Cheers. Ball two. More cheers, some boos. Ball three. Booooooos. “I could see Spiller was trying to aim the ball,” Yastrzemski said later. “It was coming in at 80 mph.”

With a 3-0 count in his favor, 33,491 screaming for him to whack one, to go out like Ted did, Spillner wound and delivered.

The pitch, Yaz could see right off, was high. Up in his eyes. Williams would have taken it, no question. That was his way. If it was a fraction of an inch off the plate, he’d take it. Period. So he’d go out with a walk. Fine.

Yaz just couldn’t. He and all those who came to cheer for him had too much riding on the pitch.

He swung from his heels and lifted a high pop-up to second baseman Jack Perconte. He laughed as he ran down to first base.

“I was trying to jerk it out,” he admitted later.

He trotted back out to his old post, left field, in the eighth and Red Sox manager Ralph Houk, like Mike Higgins had done with Ted Williams years earlier, sent a substitute out to take his position.

Yastrzemski left to deafening roars and stopped on his way to the dugout to give his hat to a youngster seated along the rail. In the locker room afterwards, Yastrzemski ordered champagne for all the writers and even toasted them for their fairness as they stood around his locker. He even remembered some of the writers who’d covered him early in his career who had since passed away. Ted Williams might not ever have talked to him again if he knew that.

There was something going on inside Yastrzemski. Never a forthcoming interview, he suddenly opened up, as if it were a great relief to him to have this career thing over with.

“I’m just a potato farmer from Long Island who had some ability,” Yaz said then. “I’m not any different than a mechanic, an engineer, or the president of a bank.”

The emotions, he was astonished to see them keep coming. Earlier in the day when he had his turn at the microphone before the game began, he spoke with such feeling, he had to halt a couple times to collect himself.

“I saw the sign that read ‘Say it ain’t so, Yaz’ and I wish it weren’t. This is the last day of my career as a player, and I want to thank all of you for being here with me today. It has been a great privilege to wear the Red Sox uniform the past 23 years, and to have played in Fenway in front of you great fans. I’ll miss you, and I’ll never forget you.”

The great thing was, for those who saw that final weekend in person or on TV, they won’t need any final home run in his last at-bat to keep it in their memory.

Yes, the signature Yastrzemski moment came the day before when, without any warning, Yaz broke away from a sweet pregame ceremony around the pitcher’s mound and impulsively began to trot along the fence down the right-field line, reaching up to slap hands with a wildly excited Fenway crowd along the way.

Amazingly, he just kept going. All the way around the ballfield. No player had ever said good-bye like this. Organist John Kiley, catching the moment perfectly, soared through “My Way” while Yaz kept waving, slapping hands down the line. He finally reached the 380 sign on the right-field bullpen wall where 23 years earlier, Williams had flied out in his next-to-last at-bat.

Then Kiley brilliantly swung into “The Impossible Dream,” the unofficial theme song for Yaz and the Red Sox’s improbable pennant drive 16 years earlier, his greatest year as a baseball player, and the joint melted. By the time Yaz crossed through right center and center field, still waving, misty-eyed himself, Fenway was a sweet, soggy mess.

No, it didn’t seem 16 years ago. Yaz and all of Red Sox Nation were young again. Finally, Yaz’s trot got to his old workspace, left field. Seeing him jog across the worn grass, it had never occurred to Red Sox fans that someday he would leave that spot. It was if he would always be out there, like a lawn ornament.

Once he got to the left-field line, Yaz moved back along the edge of the wall, slapping hands with fan after fan while Kiley swung into his third number, an emotional “Auld Lange Syne.” Yaz stopped to shake hands with a few Indians’ players, then stood at home plate, waving, his eyes wet, his lip trembling.

By the time he was back in the dugout, it didn’t seem as if he’d be able to play. And that was only Saturday. Of course, Yaz did play and went 0-4, grounding out four times, including the game’s final out.

There was one great surprise left. On that final Sunday, after that glorious last at-bat pop-up, Yaz stayed in the dugout until the game and season ended. As fans were emptying Fenway feeling a little downhearted, he magically appeared again, in an undershirt, and trotted back out onto the field and gave them his own instant replay, starting down the right-field line and taking the whole park in one last time.

With a thunderous roar from the Red Sox fans still there, Carl Yastrzemski took one final, triumphant tour around the field. Call it a victory lap.

John Nogowski’s two baseball books - “Diamond Duels” and “Last Time Out” are available on Amazon and locally at Barnes & Noble and Books A Million.

Yaz was a class act! Said by a Yankee fan

OK lol! I gasped thinking you meant Yaz - the band.