Thinking about The Basement Tapes

Did Dylan and The Band stop time or kill it?

EDITOR’S NOTE: In these troubled times, one thing music can provide for us is precisely what it brought Bob Dylan and members of The Band (minus Levon Helm) in the summer of 1967 — peace. Re-reading this piece this morning, something written last summer before all sorts of things happened to me and our country made me think about The Basement Tapes, why they appeal to us so much. It also made me think about why for Bob Dylan, their appeal remains puzzling, mysterious. What they meant to him then was so very different than what they mean to us, especially now.

They seem to be written inside of a bubble, when Bob and four-fifths of The Band were able to stop, or at least ignore, time. By doing that, what seeps in is a certain joy, a delight at having a musical gift, a verbal facility and the space and time to just create. Not to sell records or climb the charts. Just for themselves. For fun. For one another. And unwittingly, they cut us in, too. Took a while, sure.

Greil Marcus famously wrote a book about these recordings, at least some of them, in a book originally called “Invisible Republic.” He talked about them “killing time.” Respectfully, I don’t think they were “killing time,” but savoring the moment, in that old phrase “seizing the day.” That Garth Hudson had the wherewithal to actually record some of these — who knows what we lost! — is our great luck. Yes, I was one of the ones who actually drove to the house, sat outside of it and listened. Still listening, all these years later. I bet you are, too.

“Big Pink,” the one-time home of three-fifths of The Band, is located out on Parnassus Lane at 2188 Stoll Road in Saugerties, New York, set in the middle of the majestic Catskill Mountains, surrounded by acres and acres of pine trees and oaks and maples and not much else. Literally, it’s the middle of nowhere.

Driving through Woodstock years ago, I had to find it myself. It took a little while but I finally did, parked in front of the house, rolled the window down and listened, just in case there was still an echo from a magical summer all those years ago.

On an afternoon exactly like this one 59 years ago, maybe you were out for a walk or a drive or lost and you might have heard music coming out of what seemed like the little basement of that home. You might have heard music in the afternoons for quite a few months back in 1967. For it was down in that basement, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Robbie Robertson, along with regular visits from a famous neighbor, Bob Dylan, where the five of them would get together and play. And escape. And wait for the world to change. Seems idyllic now, doesn’t it?

Wouldn’t you just as soon spend your afternoons coming up with funny, playful, musical yarns for your — and their — entertainment. Not for any particularly pressing reason other than to get away from the daily hum, to reconfigure your life, what were your priorities, after all? At that moment, they had life’s greatest gift. Time. What to do? Where to go? Keep playing, it’ll come to you.

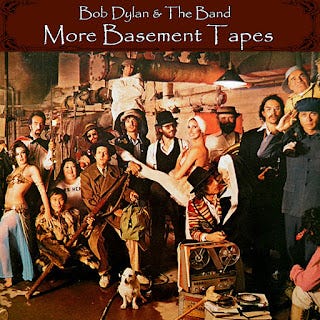

The album cover for Columbia’s “The Basement Tapes” in 1975. Later, they found even more.

It was in the summer, some 123 years earlier — July 4, 1845 — another writer named Henry David Thoreau went to the woods, too at woodsy Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts. His goal was to live “deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Maybe Dylan read Thoreau, maybe he didn’t. But wasn’t there something similar sending him up to Stoll Road five days a week? Sure, he played and wrote music for a living and it wasn’t his fault that what he wrote seemed to cause such a fuss. After that motorcycle accident, following up a brutal world tour, he needed and wanted to take a break, take stock of where he was, where he wanted to go next. It wouldn’t be a reach to say he wanted to front the essential facts of his life, too, didn’t he? The record company wanted more, the listening public wanted more, but they just had to wait. Hell, they held a gynormous festival just down the road, hoping he would show. Nope.

The world then, as now, was in a mess. Vietnam, racial issues, the country just wouldn’t settle down. And perhaps, one of the reasons it wouldn’t settle down was that notable neighbor, who’d drive up to Big Pink just about every weekday, let himself in, make a pot of very strong coffee (from all reports), then, sit down at a typewriter and start throwing together words, lyrics, freewheeling tales of instantly memorable characters who magically pop up on that typewriter with dizzying regularity.

They weren’t anthems, “finger-pointing songs” as he called a few of his oldies. The songs went deeper in some ways and were just skating across the carnival of humanity in others. He wasn’t trying to impress anyone or speak for his generation. He wanted to play — in the very literal sense of that word — and let the world go on without him. At least for a while.

Big Pink, where Bob Dylan visited The Band on a regular basis

Wouldn’t you like to do that, too? Let the world go on without you. For a summer. For a while. Find a spot out in the middle of nature, no car horns, traffic lights, billboards, no signs of civilization, really. Whatever noise there was, you were making it. With your friends. Making it together. For one another. For fun.

The songs they recorded deep in woods of the Saugerties weren’t ever supposed to be heard. Dylan famously told Band guitarist Robbie Robertson that they ought to burn them. But fortunately for us, they didn’t. Maybe they can help us now the way they did then for Bob and The Band.

That collection of songs, “The Basement Tapes” they were called, came at us in three waves. First, there was a bootleg that came out, the first bootleg, really, called “The Great White Wonder” that sneaked out some of these songs. Rolling Stone Magazine’s Jann Wenner wrote a story in 1968, calling for their release, especially since it seemed Dylan, recuperating from that motorcycle accident and being booed by most of the world on that tour, had pretty much gone silent.

Though Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” album came out with no publicity just a couple days after Christmas in 1967, a late Christmas gift, that spare record was barely a whisper, hard to hear. The rest of the music world, it seemed, was immersed in what the recording studio, technology, knobs and tape loops and dials and wizardry was available. Albums like The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s,” “The Rolling Stones” “Satanic Majesties Request,” were about as far away from the homely sounds coming out of that basement that summer as you can get.

Somebody, might have been Robbie, joked that they were rebelling against the rebellion, something like that. Playing music in a basement, surrounded by cement blocks, an old furnace, maybe a dog on the floor, his tail keeping time with the music.

Eight long years later, a two-record set, just a smidgen of what the bunch of them had actually recorded that summer, hit the stores to a great response and buoyant sales. Dylan was surprised, saying he thought fans already had ‘em. But two measly records wasn’t enough, particularly since some of the most famous numbers that had leaked out to the world — “I Shall Be Released” and “The Mighty Quinn” — weren’t on it.

So, they kept digging, supposedly Neil Young, of all people, had one of the master reels, and in 2014, out popped a six-disc, 138-song box set, over six and a half hours of music from that magical getaway summer. People loved it. There was no other music quite like it. It was, as Greil Marcus titled a book about them, they found themselves in an “Invisible Republic,” letting the music — not the world — take them some place. And it did.

The Band’s “Music From Big Pink” came out of those basement sessions. And Bob wandered into country music which seemed almost scandalous at the time and far, far away from the edge, the ledge he had walked on just a few years earlier. Sure, there were bigger, better things to write than “Peggy Day” but, what was the rush? He had time.

You and me, maybe like Dylan and the young guys from the Band way back then, need to pull away. It was the wise thing to do. Like that song lyric “Make the world go away.” For a while.

The Basement Tapes, accidentally, of course, did just that for Garth and Rick and Richard and Robbie and Bob. You might call it a holding pattern — there was no big tour or record to promote — they were just having fun, making daily discoveries about what music, the noise they were collectively making out in the Saugerties’ woods, could bring them. Joy, for one thing, all of them pitching in just for the fun of it. There was plenty to worry about — if you looked — but those problems would still be there tomorrow. And the day after. And the day after that.

Maybe we need to remember there’s still time to smile, to laugh. To care about each other, the way The Band propped up Bob when, for most of a tour across the whole wide world, it sounded like that world was against him. He came to them to regroup, to “front only the essential facts of life” you might say, writing songs, singing them. For friends. Fellow travelers. Brothers, even.

There’s a lot not to like out there, there always will be. But maybe The Basement Tapes are there to remind us we can get through this the way they did that magical summer 59 years ago. Together.

I really enjoyed reading about The Big Pink again. It’s an important part of music history to many of us. I’d probably stay a little too long if I ever went there, Lol! I appreciate your thoughts on the time of peace and healing, resulting from those sessions. Bob needed this time and fellow musicians. Someone who, in my reading, also made a great impact on Bob coming back to himself, is George Harrison. As always, thank you, John!