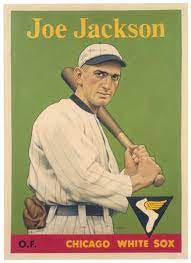

EDITOR’S NOTE: Yesterday, Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred lifted Pete Rose, Joe Jackson and the rest of the Black Sox off the permanently ineligible list for the Baseball Hall of Fame. For the great “Shoeless Joe” Jackson, it might clear the way for him to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2028 after a 2027 vote. In my 2022 baseball book “Last Time Out,” I tell the story of “Shoeless Joe’s final major-league game on September 27, 1920 as news of the fixed 1919 World Series broke. Ironically, Joe Jackson slammed a game-winning double to give pitcher Dickie Kerr, the one White Sox pitcher who was trying to win in 1919, a victory. Here’s an excerpt from “Last Time Out,” my collection of stories about the final MLB games of 43 of baseball’s all-time greats. The book is available locally at Books A Million and Barnes & Noble.

SHOELESS JOE GETS CALLED OUT

DATE: September 27, 1920 SITE: Comiskey Field, Chicago, Illinois

PITCHER: George Hauss of the Detroit Tigers

RESULT: Game-winning double Joseph Jefferson “Shoeless Joe” Jackson wound up what might have been a Hall of Fame career with a game-winning two-bagger off George “Hooks” Dauss in the sixth inning of a scoreless game against the Detroit Tigers on September 27, 1920. The hit made a winner out of Dickie Kerr, the White Sox hurler who won two games in the infamous 1919 World Series, dumped by the White Sox to the Cincinnati Reds.

By now, the noise was deafening. So persistent, so unmistakable, there seemed to be no way to keep it quiet any longer. “Shoeless Joe” Jackson stepped out of the dugout at Comiskey Park and looked around him. He could just feel it. The season was almost over. They were just a game behind the Cleveland Indians, just one game, and they could do it.

Here it was, the sixth inning of a scoreless duel with Detroit and a win might put them right at the top of the standings. He hefted his trusty 48-ounce bat, “Black Betsy,” and looked out at George “Hooks” Dauss, the Detroit Tigers’ starter, who had just hit Buck Weaver with a pitch. With number three hitter Eddie Collins up next, maybe Collins could get Weaver into scoring position and Jackson would get a chance to give his club, charging hard at the American League pennant, the lead. Not only in this game but also in the American League race. Jackson hefted the bat again. It was hard to think about only baseball.

He wasn’t reading the newspapers, that was for sure. Shoeless Joe couldn’t read. But he could hear the talk. Everywhere he went. He knew this kettle was about to boil over. Ever since Jackson and the rest of Kid Gleason’s heavily favored Chi cago “Black Sox” had fumbled away the 1919 World Series to the Cincin nati Reds, there had been talk in town that things weren’t on the square. Of course, they weren’t.

And now, thanks to the damn Cubs and their gambling talk, it was everywhere. It wouldn’t go away. Ever. Back at the start of the month, there was a story in the Chicago Tribune about an attempted fix of a midweek game between the Cubs and Phillies. Cubs management, eager to dispel the notion that there was anything shady about that game—they’d seen the World Series the year before—pitched ace Grover Cleveland Alexander out of turn and even offered him a $500 bonus if he won. But Alexander lost.

The stench from the story seemed to linger in the Windy City. A week later, with the White Sox surging, the Tribune’s I. E. Sanborn was able to write like a prophet. “Procrastination has proven the thief of something more valuable than time in the case of professional baseball ver sus gambling,” he wrote. “It has cost the game a considerable portion of its good reputation. . . . If the promoters of professional baseball had heeded the warnings dinned into their ears for years against the inroads of the betting fraternity on their business they would have headed off much of the trouble that has come to them, and which is still coming to them.”

Jackson heard the talk in the locker room. He was worried. He knew he shouldn’t have come to the big league all those years ago. He first played in Philadelphia. He was 19. Why, it took him three tries to get to the big city. Playing for the Greenville, South Carolina, team, he was summoned to play for the Philadelphia Athletics. Jackson was scared by the size of the town, the Chicago Tribune said. “The Athletics’ scout, on the first attempt to get Jackson north, succeeded in piloting him as far as Charlotte, North Caro lina, when the boy decided he has gone far enough and leaving the train, he hid from Ossee Schreckengost.”

A day later, the boy showed up in Piedmont country. “What’s the matter, Joe? Don’t you want to be a big leaguer?” friends of the young star asked. “No, them places is too big,” Jackson said. “Pelzer, Piedmont, and New berry just about suits me.”

On the second trip, the A’s scout got Jackson 200 miles closer, getting him into rural Virginia. But one look around at the cotton fields and smokestacks and Joe got lonesome for South Carolina again and left.

On the third try, he made it to Philadelphia and played for Connie Mack, who let him go to Cleveland the next year. He’d been in Chicago since 1915. Hell, he thought, I should of stayed in South Carolina. What a jam he was in now.

It wasn’t the first time that shady things had happened in baseball. There had always been talk about gamblers and players laying down. Hal Chase himself was good for a scandal or two a year. There was always that kind of talk around the game, gamblers asking who was hurt, whose arm was ailing, who was hitting?

Sure, sometimes strange things happened at the end of a season. Just nine years earlier, Cleveland’s Napoleon Lajoie thought he won himself a car (and the American League batting title) by collecting eight hits, including seven straight bunts in a final-day doubleheader to slip past Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers, who chose to sit out the last two games and protect his lead. Or so he thought.

It turned out that Lajoie tripled his first time up. Then St. Louis Browns third baseman Red Corriden, a rookie, and Browns manager Jack O’Connor got the word to him that he should simply bunt. He didn’t have to go through all the trouble of hitting triples. It was also hinted that the Browns’ strategy was greeted with the strong encouragement of the rest of the Detroit Tigers, who didn’t want the hated Cobb to get the car. So Lajoie got his hits and was so eager for the car and the batting title that after the game, he actually called the game’s official scorer Richard Collins, to ask him if he didn’t think one of the fumbled bunts by Corriden should have been ruled a hit, which would have given him nine on the after noon.

Cleveland’s Napoleon Lajoie and Detroit’s Ty Cobb each received a Chalmers automobile after their contentious battle for the 1910 American League batting title.

According to a story in the Chicago Tribune, Harry Howell, a former Browns pitcher, even offered Collins a $40 suit if he’d change the call to help Lajoie out. Collins refused. Ultimately, Cobb was declared the winner, thanks to a clerical error by the American League office, where one of Cobb’s games was counted twice. Lajoie’s hits—legit or not—stayed on his lifetime record.

Corriden, a rookie, was forgiven. Manager O’Connor got himself suspended indefinitely. Jackson knew about all that stuff. There was plenty more. All the stuff Hal Chase did. There were so many. But the one he was involved in, he couldn’t shake.

Blowing a World Series was a different story. And for most of the season, it seemed that guilt hung over the White Sox players like a shroud. Though it had four eventual 20-game winners and Joe Jackson was hitting .382, a 31-point improvement, the White Sox struggled early in 1920. Buck Weaver was up 37 points to .333 and Hap Felsch and Jackson were among the top 10 in the league in home runs: Felsch had 14, Jackson 12.

Yet for most of the season, it was Cleveland and New York battling it out for the lead. The reigning American League champion White Sox, with the whole team back, were having a tough time. Near the end of the season, as the rumors grew louder, something clicked. Maybe it was a shot at redemption. Nobody knows for sure, but Gleason’s club took off and made a run at Tris Speaker’s eventual pennant winners in Cleveland, winning 10 of its last 11 games, climbing within a half-game of the American League lead.

Why, if they could just get back to the Series, they could make it all right again. In mid-September, the last time Jackson played against Babe Ruth and his Yan kees, Eddie Cicotte, the same Eddie Cicotte who let himself get lit up in the World Series as part of the fix held Ruth (who’d hit 54 homers that year) to a harmless single and the White Sox pounded New York, then the AL leaders, 15–9. The Yankees were worried. Nothing, it seemed, could stop these Black Sox.

They all talked about getting back into the World Series, winning the damn thing and it’d be done with. It seemed as if that was indeed fueling Gleason’s club, who were roar ing. But a grand jury investigation had begun. Everybody on the Black Sox got nervous. They knew someone would talk about gambling and baseball. Their dirty not-so-secret would soon be out.

“Baseball is more than a national game,” the jury foreman said at the time, “it is an American institution, (our great teacher of ) respect for author ity, self confidence, fair-mindedness, quick judgment, and self-control.” And as the trial gathered, the talk in town was rampant. A few days later, a letter to the Chicago Tribune from Fred Loomis, a heartsick White Sox fan, seemed to speak for all of Chicago. And you can imagine how the hearts of these Black Sox sank as his letter hit the press.

Jackson heard all the guys talking about it. They weren’t a close bunch, really, but now, this was going to be troublesome. “Widespread circulation has been given to reports from various sources that the World Series of last fall between the Chicago White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds was deliberately and inten tionally lost through an alleged conspiracy between certain unnamed mem bers of the Chicago White Sox and certain gamblers . . .” Loomis wrote.

And the buzz continued. By September 20, Gleason’s White Sox had passed the Yankees and were within a game of trying to win themselves an American League pennant by outdueling the red-hot Cleveland Indians, taking two out of three.

In that last game in Cleveland, where Jackson first became a big-league regular, the crowd was nasty. Jackson had hit his final big-league homer in the fifth inning and with the crowd chanting nastily “Shipyard, shipyard”— mocking Jackson for refusing to enlist in the Army for World War I, prefer ring instead to work in a shipyard in Cleveland. Feeling the pressure of everything mounting on him, Jackson lost his cool and made an obscene gesture when he hit third base, then did it again when he crossed home plate. Things were turning ugly.

THE STORY OF THE “FIX” BREAKS

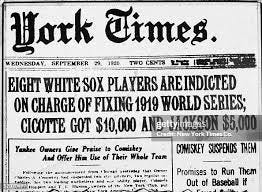

On September 23, the dam broke. The banner headline in the Chicago Tribune would echo through history. “‘Fixed’ World Series. Five White Sox Men Involved Hoyne Aid Says.” The investigation of the Alexander fix attempt had stirred a hornet’s nest. It turned out too many people were ask ing too many questions. Cubs infielder Charles Herzog and Art Wilson, a Boston Braves reserve catcher, were the first two players to give affidavits about the rigged series.

Meanwhile, the White Sox kept playing against a clock they knew was running out. Next up were these Tigers here in a midweek series. If they could just catch Cleveland, maybe they could put off this trial. Back at the ballpark, Jackson heard the Comiskey Park crowd roar as Collins’s single drove Weaver over to third. Here was his chance. It was up to him and “Black Betsy.” He looked over in the dugout to the White Sox pitcher that afternoon, fresh-faced Dickie Kerr, who was working on a six-hitter.

Kerr, Jackson remembered, was the guy who didn’t know the fix was on in the Series and won two games against the Reds in spite of it. Now he had a chance to win one for him—legitimately. He unleashed that picture-perfect swing one last time and launched a shot into the right-center-field gap, just beyond Ty Cobb’s reach. Weaver came charging around and when Cobb botched the relay throw, so did Collins.

Jackson pulled into second, the noise of the Comiskey Park crowd ringing in his ears one last time. It was the 1,774th and final hit of Jackson’s career, his 120th and 121st RBI of the season, the only time in his career he drove in more than 100 runs.

The game, a 2–0 White Sox win and Shoeless Joe Jackson’s last big league game, was over in just 75 minutes. When he got into the clubhouse at the end of the game, the guys were reading the papers from Philadelphia, where the story broke. Billy Maharg had talked and explained the whole deal. This wasn’t good.

The next day, Jackson, like the other seven White Sox play ers involved in the World Series scandal, was ordered to appear before the grand jury. They were just one game out. They could win this thing and get them all off their back. Why now? Why now?

When he got his turn before the grand jury, Jackson was blunt. “I wanted $20,000 for my part in the deal and (Chick) Gandil told me I could get that much out of it,” he said. “After the first game, (Lefty) Williams came to my room at the hotel and slipped me $5,000. He said the rest would come as soon as we showed the gamblers we were on the square with them. But that is all I ever got. I raised a howl several times as the games went on but it never got anywhere. I was hog-tied.”

And when he talked about the games themselves, he explained how eas ily a game could be rigged. “I am left fielder for the Sox,” he told the jury. “When a Cincinnati player would bat a ball in my territory, I’d muff it if I could. But if it would look too much like crooked work to do that, I’d be slow and would make a throw to the infield that would be too short. My work netted the Cincinnati team several runs that they would never have made had I been playing on the square.”

Once the players were on the grand jury list, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey had to indefinitely suspend those eight players for the rest of the regular season. The team didn’t win another game. Other teams around baseball offered to lend Comiskey their players for the rest of the season. It was quite a show.

Cleveland won the pennant and went on to thump Brooklyn in the World Series. The jury ended up acquitting the “Black Sox,” but it was a hollow victory. There had been so much dirt unearthed from the testimony that new com missioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, hired to clean up the sport, had no choice. He banned all eight of them—for life.

“Regardless of the verdict of juries,” Landis wrote, “no player who throws a ball game, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame, no player that sits in confidence with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed and does not promptly tell the club about it, will ever play professional baseball.”

Shoeless Joe Jackson’s .382 final season was the fourth-highest of his career and strongest season in eight years, and raised his career mark to .356, ranking him third on the all-time list. The 1920 campaign was the 33-year old Jackson’s final one in the big leagues. His 13th season.

Author John Nogowski’s two baseball books - “Last Time Out” and his new book, “Diamond Duels” are available locally at Barnes & Noble and Books A Million. Nogowski will be doing a book signing at Barnes & Noble on May 31 from Noon to 2.