It seems to me that it was William Faulkner who said once he’d “written and sent a lot of things off to print, never realizing that someone would actually read it.”

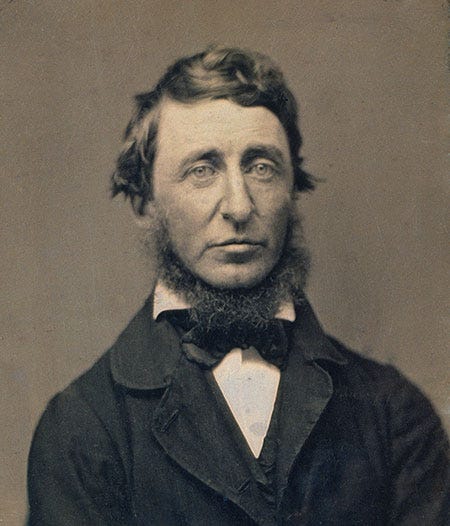

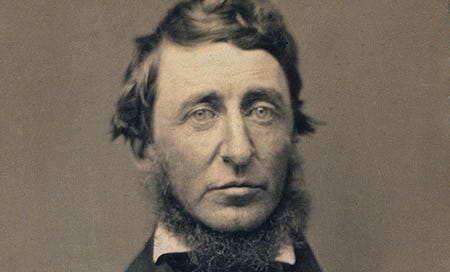

I don’t think that was the case for Henry David Thoreau. Though holed up in his one-room cabin near Walden Pond for a couple of years, discovering himself as a writer, he seemed to me to be writing for down the road, well past his contemporaries, whom I sure he felt wouldn’t understand him. (And they didn’t.)

Though I grew up only about 40 minutes from Concord, Massachusetts, Thoreau really wasn’t on my radar until college. I had an older woman friend who was a huge Ralph Waldo Emerson fan, she tried to convert me but Thoreau, what little I’d read at the time, seemed a lot more practical, sensible, stubborn, unrelenting.

While I wasn’t particularly practical - anybody who ever watched me try to assemble a bike would testify to that - the other Thoreauvian elements seemed to suit me. It wasn’t really until I started teaching that I not only began to recognize, appreciate, get excited by his work, I made sure to share it with my classes with the play “The Night Thoreau Spent In Jail” and excerpts from “Walden” and “Civil Disobedience.”

My classes were all largely African-American, so recognizing that Thoreau was an abolitionist, someone who was out front against slavery a good ten years before Abraham Lincoln did, impressed them. As did, I think, the pungent way he wrote things. The writer E.B. White referred to Thoreau’s writing as like an anchovy spread (without the scent!)

“Walden” is so indigestible that many hungry people abandon it because it makes them mildly sick, each sentence being an anchovy spread, and the whole thing too salty and nourishing for one sitting. Henry was torn all his days between two awful pulls — the gnawing desire to change life, and the equally troublesome desire to live it.”

I like that quote. And when I read “Now Comes Good Sailing” a collection of 27 essays by an assortment of authors on their reading of Thoreau, absorbing both his influence and flavor in varied writing styles and also on topics far afield from him. Somehow, it brought me and my heart closer to the former Walden resident who carried frogs in his hat, didn’t even have a bathroom at his home and had a wicked sense of humor that he masked as expertly as his own heart.

In Allen Cunningham’s “Thoreau Was Funny As Hell” for example, he writes: “Depicting himself ironically well-employed as nature’s surveyor and inspector in Walden’s first chapter, he boasts: “I have watered the red huckleberry, the sand cherry and the nettle tree, the red pine and the black ash, the white grape and the yellow violet, which might have withered else in dry seasons.” Like much of Walden’s wit, the Falstaffian irreverence here, wherein Thoreau confesses to being a serial outdoor pisser, went—to deploy a pun of my own—whizzing right over the teenage reader’s head.”

In “Now Comes Good Sailing” there are all sorts of wonderful essays where an assortment of writers try to do with Henry what Kurt Vonnegut said he tried to do with his idol - “I’ve tried to think and write with Mark Twain’s brain.”

In “Wild Apples,” the opening essay by Lauren Groff, she says “I discovered a love so powerful for Thoreau’s energetic vision that it often took my breath away. I saw the wicked humor in the book, the laughing absurdity of what I’d taken twenty years before to be only tiresome bragging. Thoreau’s sentences have such vigor that they sometimes made my body need to stand up and pace to dissipate their pent energy.”

In Gerald Early’s “Walden And The Black Quest For Nature” he quotes Thoreau on the futility of one generation helping another - something we all can relate to these days. “One may almost doubt if the wisest man had learned any important advice to give the young, their own experience has been so partial, and their lives has been such miserable failures…I have lived some thirty years on this planet, and I have yet to hear the first syllable of valuable or even earnest advice from my seniors. They have told me nothing.” “For the baby boomers,” Early writes, “this was the anthem of their age.”

And for such a serious-seeming guy, George Howe Colt’s playful “Thoreau On Ice” reveals a whole other side to Henry, reading of his passion for ice skating and exploration, a sense of adventure, Thoreau happily, crazily skating on the frozen rivers of Concord and thereabouts in the dark and cold New England winters, loving every minute of it.

Or maybe you’ll enjoy the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik’s “A Few Elements of American Style” where he again talks about White and Thoreau and their writing styles with crackling insight.

“Thoreau, in “Walden,” seems, to us reading him now, a writer who lives in and out of his own best voice,” Gopnik says. “Many passages and sentences in “Walden” are conventional nineteenth-century neoclassical, replete with surprising stock images and exhortary rhetoric like this: “I do not mean to prescribe rules to strong and valiant natures, who will mind their own affairs whether in heaven or hell, and perchance build more magnificently and spend more lavishly than the richest, without ever impoverishing themselves, not knowing how they live, IF, indeed, there are any such, as has been dreamed; nor to those who find their encouragement and inspiration in precisely the present condition of things, and cherish it with the fondness and enthusiasm of lovers - and, to some extent, I reckon myself in this number.”

Mighty, huh? Was he writing for us, in the future? Perhaps, sitting alone on the step of his little hut, looking out at the trees around him, squirrels running around, thinking to himself, “Someday, people will get it, they’ll see I was right all along.”

As I wrote a while back, I’m still steaming about Kathryn Schulz’s “Pond Scum” hatchet job article which appeared in The New Yorker a while back. Contrary to the crap she wrote, there IS something about Henry’s words that endures, something about his approach to the world, about what he left for all of us that still fascinates. That ain’t happening to you, Kathryn, sorry about that.

If he was alive today, I do think Thoreau would both be utterly shocked at his enduring popularity and at the same time, completely unchanged by it. Reading “Now Comes Good Sailing” will convince you of that. And it will get you thinking about Henry Thoreau all over again.

When I was teaching Thoreau, I got to visit Walden and his cabin replica.

Really enjoyed this, along with my own reading of "Now Comes Good Sailing". It's exciting to read all the different ways that people have reacted to this man and his ideas.

Thanks, John!